'We'll be studying this event for years': Recent auroras may have been the strongest in 500 years, NASA says

Vibrant auroras that were recently observed by millions of people across the globe were some of the most widespread in the last five centuries, NASA says. The light shows may have also reached the equator.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

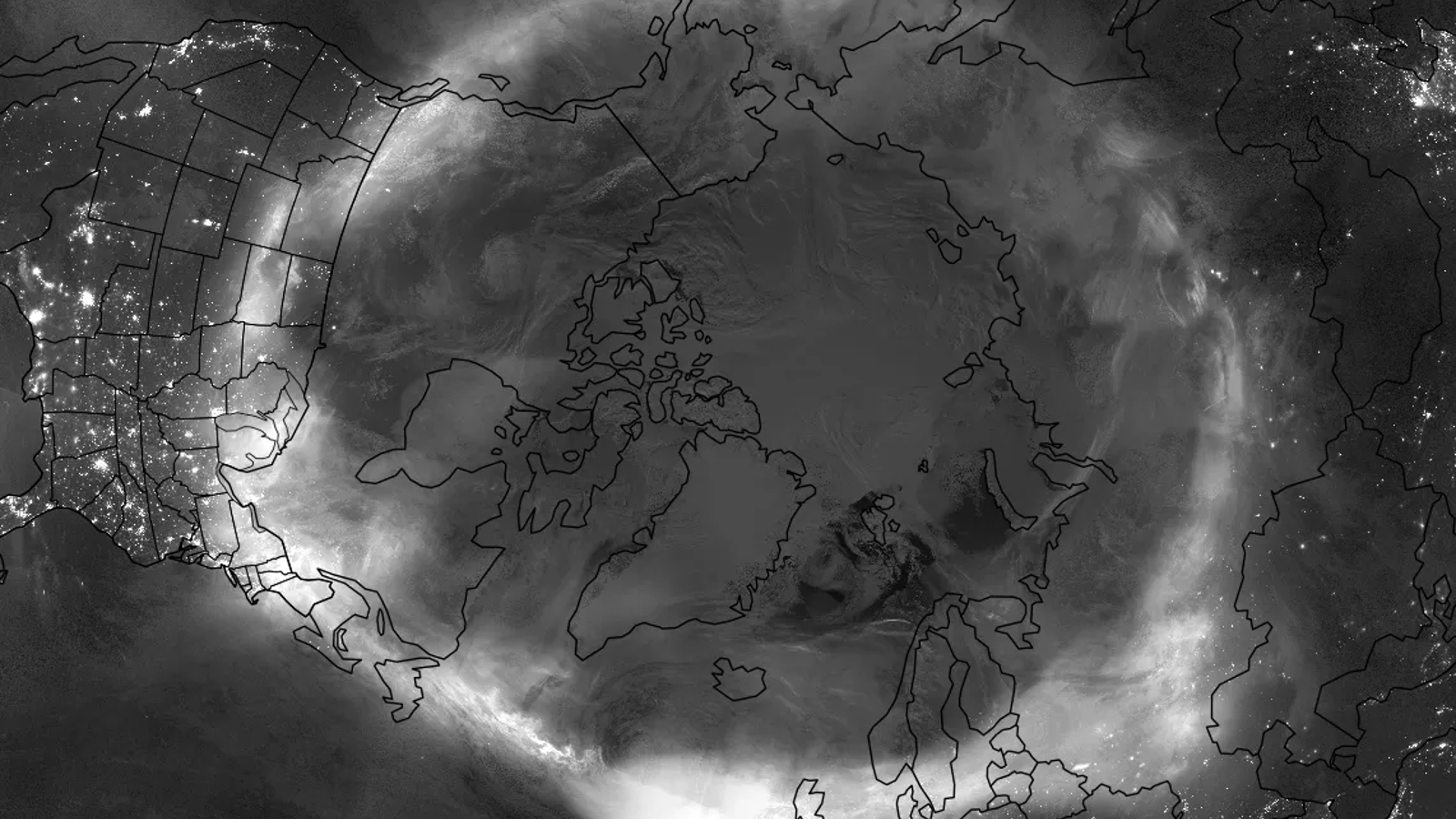

The unprecedented auroras that recently wowed millions of people across the globe were some of the most intense light shows our planet has seen for half a millennium, NASA has revealed. The dancing lights, which may have reached the equator, were triggered by Earth's most powerful geomagnetic storm in more than two decades.

Between May 10 and May 12, our planet experienced a major geomagnetic disturbance after at least five solar storms slammed into Earth back-to-back, temporarily weakening the magnetosphere. The solar storms, known as coronal mass ejections (CMEs), were launched by solar flares from the gigantic sunspot AR3664, which was more than 15 times wider than Earth at the time — the biggest dark patch to appear on the sun for a decade. Several of these solar flares reached "X-class" status — the most powerful type of surface explosion the sun can produce.

The resulting geomagnetic storm was mainly ranked as G4, or "severe," which is the second-highest class of geomagnetic storm. But on two occasions, the storm temporarily reached "extreme" G5 conditions, on par with the fallout from the Carrington event of 1859 — the most powerful solar storm in recorded history, which triggered auroras as far south as Cuba and Hawaii. This was the first time Earth experienced G5 conditions since the Great Halloween storms of 2003.

Fortunately, this superpowered storm did not cause any major issues on Earth apart from some temporary satellite and communications disruptions. However, the event did paint large parts of our planet's skies with vibrant, multicolor auroras as the weakened magnetosphere allowed large amounts of solar radiation to bombard the upper atmosphere and excite gas molecules.

These light shows covered vast areas of both of Earth's hemispheres and were "possibly one of the strongest displays of auroras on record in the past 500 years," NASA representatives wrote in a statement.

"We'll be studying this event for years," Teresa Nieves-Chinchilla, the acting director of NASA's Moon to Mars Space Weather Analysis Office, said in the statement. "It will help us test the limits of our models and understanding of solar storms."

Related: Why are auroras different colors?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Auroras normally only occur in polar regions, where Earth's magnetosphere is weakest. However, during big geomagnetic storms, solar radiation can reach much further afield.

In the Northern Hemisphere, auroras from the latest storm were spotted as far south as Florida and Mexico, as well as across large parts of Europe.

In the Southern Hemisphere, meanwhile, auroras were seen as far north as the Galápagos Islands, which partially straddle the equator, aurora photographer Chris Wickland wrote on the social platform X. However, this sighting has not been confirmed by any scientific organizations or news sites.

Auroras were also spotted in the Southern Hemisphere as far north as New Caledonia — an island nation in the Pacific Ocean between Australia and Tonga. Local photographer Frédéric Desmoulins snapped stunning shots of pink lights filling the sky, which are likely the first aurora photos ever captured on the island, Spaceweather.com reported.

"As far as we know, the last time sky watchers saw auroras in the area was during the Carrington Event of September 1859, when auroras were sighted from a ship in the Coral Sea," Hisashi Hayakawa, a space weather scientist at Nagoya University in Japan, told Spaceweather.com.

The geomagnetic storm was so strong that the magnetic disturbance was also picked up by seafloor observatories off the Atlantic and Pacific coast of Canada at depths of up to 2.7 miles (4.3 kilometers), according to the University of Victoria.

On May 14, the same sunspot unleashed an X8.7 magnitude solar flare — the most powerful surface explosion of the current solar cycle. However, this outburst did not impact Earth.

The unprecedented level of solar activity is a result of the sun entering the most active phase of its roughly 11-year cycle of activity, known as the solar maximum, which has arrived sooner and is currently more active than scientists initially expected.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus