10 solar storms that blew us away in 2023

The sun has been spitting out more frequent and intense solar storms this year as it approaches solar maximum. Here are some of the biggest.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Solar activity has kicked up a gear in 2023 as the sun nears the start of the explosive peak in its roughly 11-year solar cycle, known as the solar maximum. As a result, our home star has been spitting out abundant and powerful solar storms, as well as producing other unusual phenomena. From supercharged X-class flares and cannibal coronal mass ejections to a "canyon of fire" and solar tornado, here are the 10 most impressive solar storms from 2023.

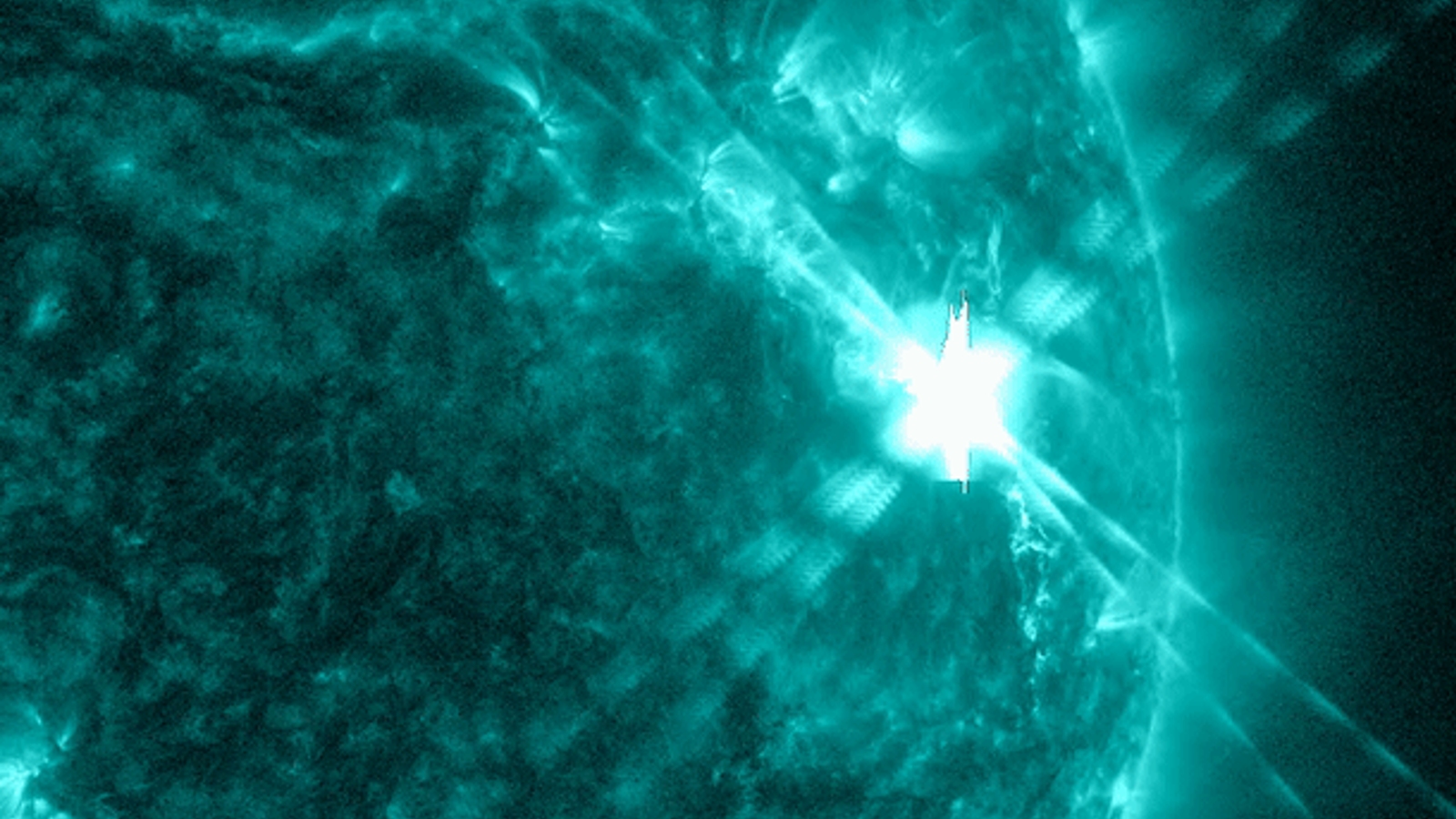

Powerful X-class flares

X-class flares are the most powerful class of solar flares that the sun can produce. Most of the time, these supercharged flares are exceedingly rare and often don't happen for years on end. But around solar maximum, they explode from the sun like there's no tomorrow.

There have been 12 X-class flares in 2023, which is more than occurred in the previous five years combined. Several of these have launched clouds of magnetized plasma, or coronal mass ejections (CMEs), that later smashed into Earth, including a surprise flare from the sun's far side from Earth, another that also triggered a "solar tsunami" and an explosion from a sunspot 10 times wider than Earth.

In December, the sun also unleashed the most powerful solar flare for more than six years, which grazed Earth with a CME and triggered a widespread radio blackout across the Americas.

We will likely see even more powerful X-class flares in the coming years.

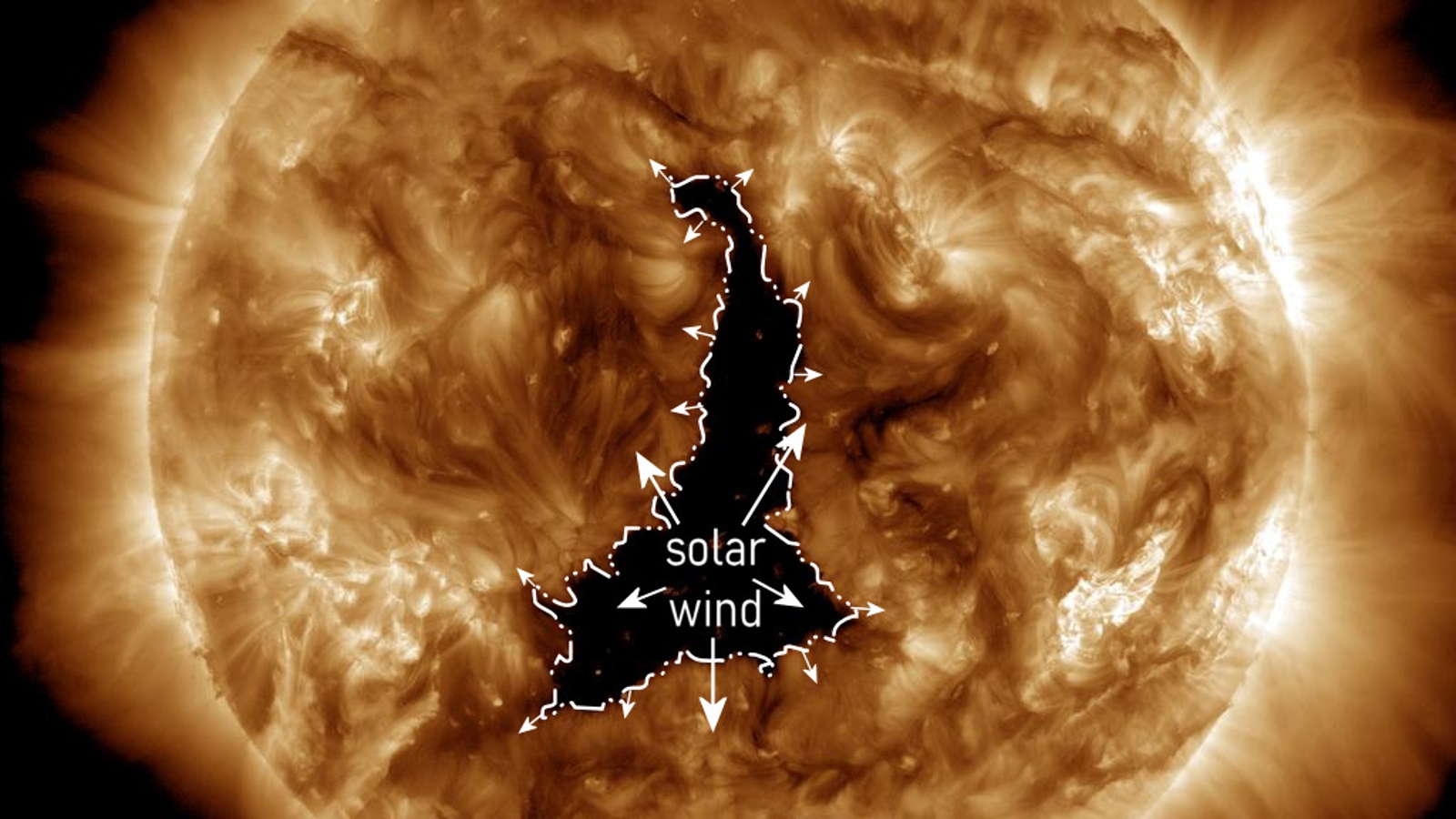

Gigantic 'hole' in the sun

In December, an enormous "coronal hole" wider than 60 Earths opened up on the sun's surface and began bombarding Earth with supercharged solar wind.

Coronal holes form when magnetic fields on the sun suddenly disappear, which allows large amounts of plasma to escape into space. The holes also send large streams of unusually fast solar wind, or radiation, shooting out of the sun.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The solar wind triggered a minor geomagnetic storm, or disturbance in Earth's magnetosphere, which resulted in some vibrant aurora displays.

Cannibal CMEs

A "cannibal" CME is birthed by successive CMEs, when the second eruption catches up to the first and absorbs it to create one massive CME with a greater destructive potential.

Like X-class flares, cannibal CMEs are normally rare but become more common in and around solar maximum. We have seen at least two cannibal CMEs this year and both have triggered geomagnetic storms on Earth. However, on both occasions, we escaped the worst effects of these conjoined storms.

There is also a high chance we will see more cannibal CMEs in the next few years.

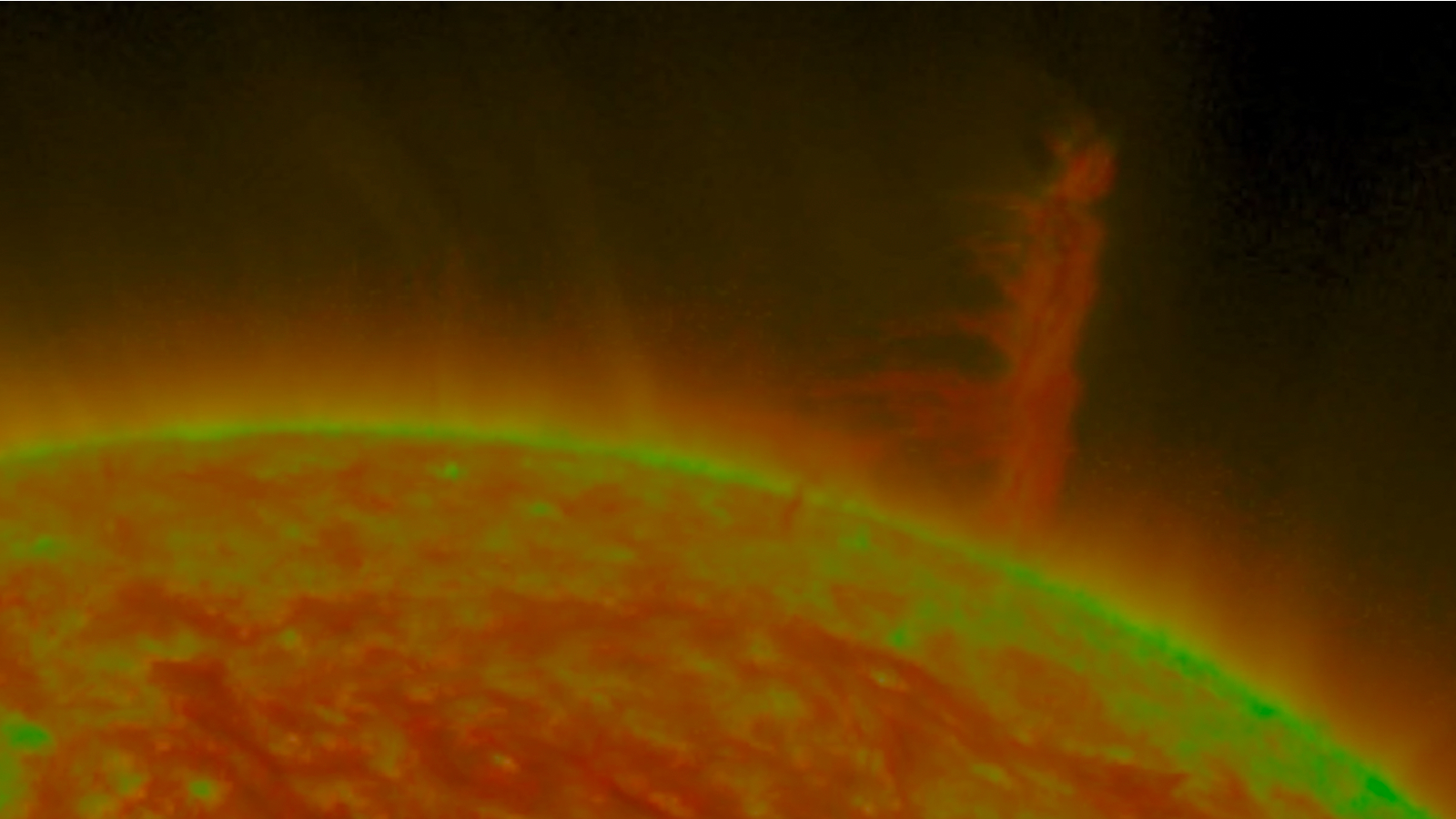

Towering solar tornado

In March, stunned astronomers watched on as an enormous tornado of fire raged near the sun's north pole for three days. The gigantic plume of swirling plasma was 14 times taller than Earth and rained blobs of plasma onto the sun's surface.

The rare phenomenon was caused by a massive loop of plasma, known as a solar prominence, becoming trapped by a rapidly rotating magnetic field. Eventually, the twister "overtorqued itself" and spat out the plasma into space.

The sun's overall magnetic field is stronger toward its poles, which allows large plasma structures like this to grow taller than on other parts of the sun. This was the tallest documented solar tornado on record.

'Canyon of fire' eruption

On Halloween, a powerful explosion from the sun briefly opened up an enormous valley on the solar surface, known as a "canyon of fire," that was more than twice as wide as the contiguous U.S. and seven times longer than Earth.

The fiery chasm formed after a large solar prominence snapped off from the sun and shot into space, leaving a massive hole behind. Eventually, the canyon closed up as surrounding plasma filled in the hole.

Scientists were concerned that the catapulted plasma could hit our planet. But in the end, it missed us completely.

'Impossible' orange auroras

There have been hundreds of incredible aurora displays across the globe this year thanks to the increase in CMEs and solar wind. On a couple of occasions, we have also been treated to supposedly impossible orange auroras, which haven't been seen for years.

Auroras are created when radiation from the sun bypasses Earth's magnetosphere during geomagnetic storms, which excite gas molecules in the atmosphere, causing them to emit light. Atmospheric gasses typically give off red and green light, while other colors such as pink are rarer. But no gases should be able to give off an orange light.

Instead, what we see as orange light is a mix of red and green light. These pumpkin-colored displays only happen when these colors align perfectly in the sky, which is very rare. But as the number of auroral displays has increased, the chance of seeing this elusive color has increased.

Enormous polar vortex

In February, astronomers spotted a massive vortex-like ring of plasma circling the sun's north pole. The show lasted for around eight hours before the swirling fire seemingly disappeared.

The vortex formed when a large solar prominence snapped off from the sun. But instead of shooting off into space, it became trapped near the sun's surface and began to spin around the star's pole, which has never been seen before.

Scientists could not explain exactly what was going on but the vortex may have been linked to the pole's stronger magnetic field, which could have held the plasma in place. The phenomenon was also similar to how cold air circles Earth's polar regions.

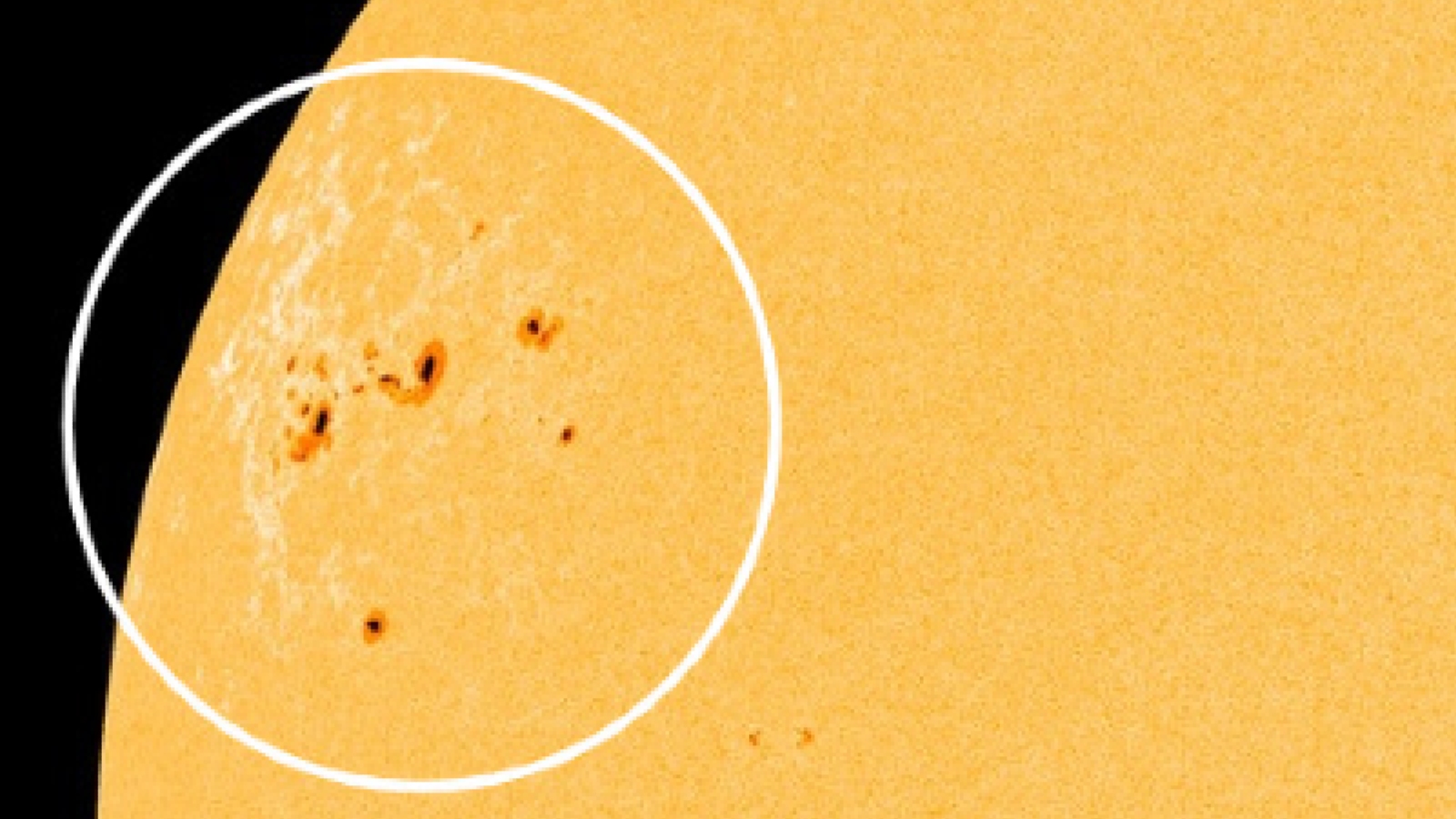

'Sunspot archipelago' bombardment

In November, an absolutely enormous sunspot region emerged on the sun's surface. The cluster of dark patches, made up of at least four individual sunspot groups, was wider than 15 Earths, making it the largest active region of the current solar cycle.

This "sunspot archipelago" spat out dozens of solar flares in the space of less than a week, which triggered several geomagnetic storms. However, the bombardment was not as bad as scientists had initially feared it could be.

In general, sunspot numbers have also increased drastically this year. In July, the number of dark patches that appeared on the solar surface was the highest for more than 20 years.

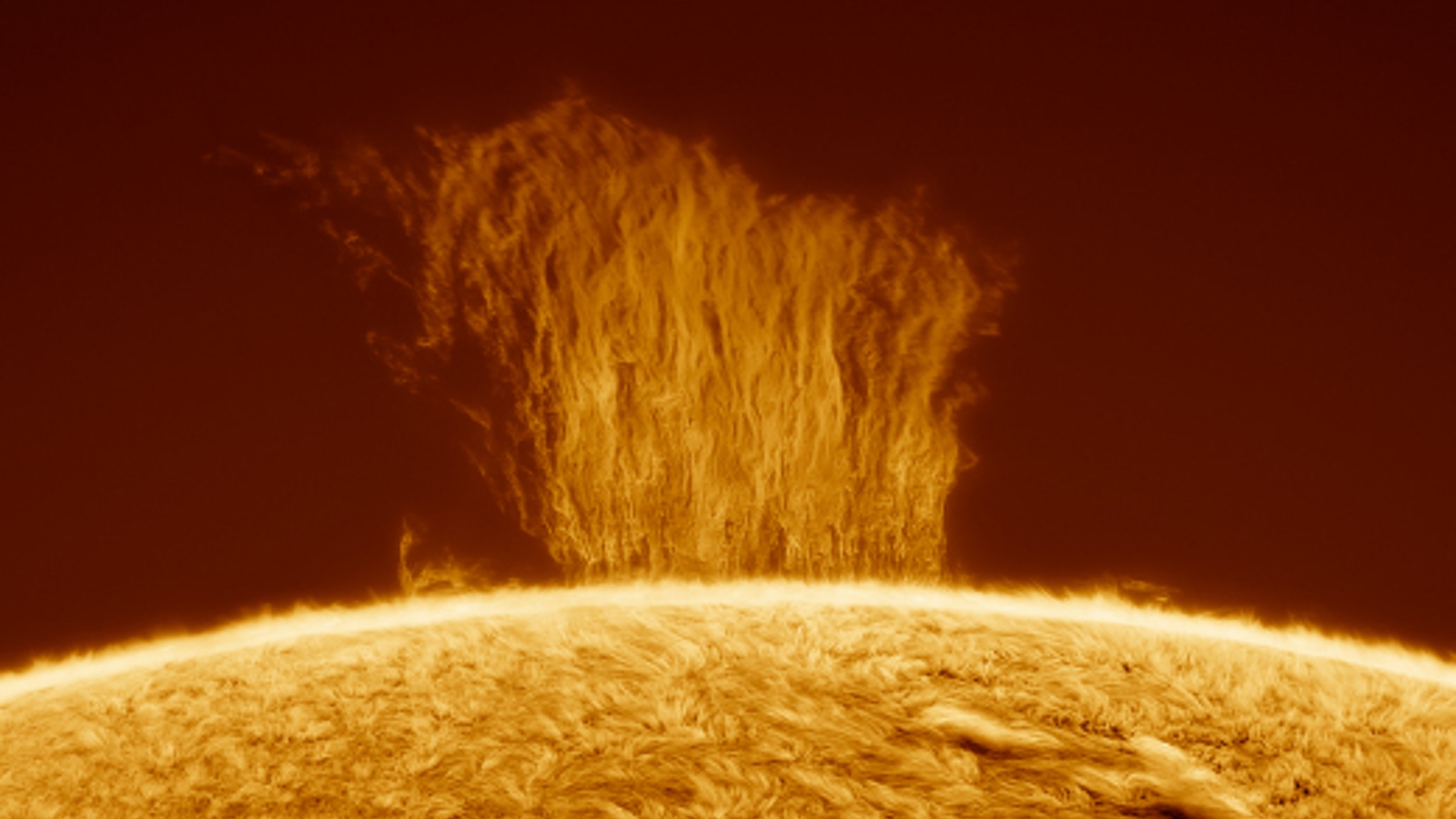

Weird plasma waterfall

In March, a massive, logic-defying plasma waterfall appeared on the sun. The wall of falling fire was taller than eight Earths stacked on top of each other.

The waterfall's official name is a polar crown prominence (PCP), which is a type of plasma loop that forms near the sun's poles and collapses in on itself due to the increased magnetic field strength. They are extremely rare but have been documented before.

Researchers are still unsure exactly how PCPs work. The puzzling phenomena start erupting slowly before accelerating and then collapsing back in on themselves and the falling plasma travels at speeds that are much higher than the sun's magnetic field should allow.

Butterfly CME

The sun has launched hundreds of CMEs of various sizes and shapes into space this year. But one of the most beautiful was a "butterfly" CME, which erupted from the sun's far side in March.

When CMEs erupt, scientists can watch them using a coronagraph, which shows how the ejected plasma ripples through the sun's outer atmosphere, or corona. Most CMEs look like rings or lopsided plumes in coronagraphs. But this CME created a perfectly symmetrical pair of butterfly wings.

Unfortunately, we will never know what caused this irregular insectoid shape because the sun blocked our view of the explosion.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus