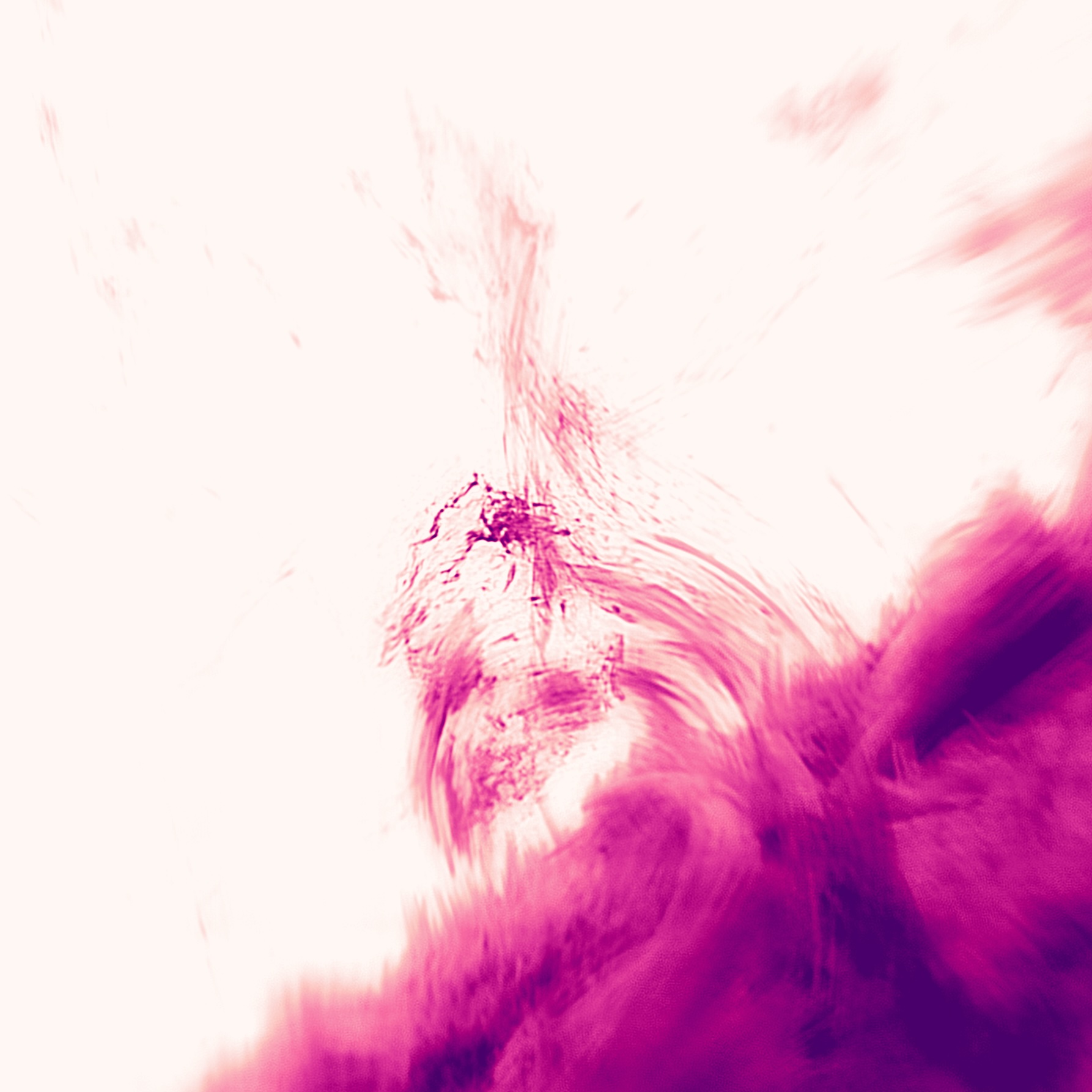

Space photo of the week: Pink 'raindrops' on the sun captured in greatest detail ever

Solar scientists have unveiled spectacular new images of plasma "rain" in the sun's corona using adaptive optics.

What it is: The sun's corona

Where it is: The outermost layer of the sun's atmosphere.

When it was shared: May 27, 2025

Solar "raindrops" — plasma streams and vast arches extending outward from the sun's surface and into the corona, the outermost part of the solar atmosphere — have been captured in spectacular new detail by a ground-based telescope in California.

Among the images taken from time-lapse movies, which utilize new technology to eliminate blurring caused by Earth's atmosphere, is coronal rain, a phenomenon that occurs when cooling plasma condenses and falls back toward the sun's surface along magnetic field lines.

Other features imaged include prominences — the term solar physicists use to describe the arches and loops — and finely structured plasma streams. The images are artificially colorized from the hydrogen-alpha light captured by the telescope, making them appear pink.

The remarkable images, taken by researchers from the U.S. National Science Foundation's National Solar Observatory and New Jersey Institute of Technology, were published this week in a paper in the journal Nature.

"These are by far the most detailed observations of this kind, showing features not previously observed, and it's not quite clear what they are," Vasyl Yurchyshyn, co-author of the study and a research professor at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, said in a statement.

The researchers captured the new images using the 1.6-meter Goode Solar Telescope at the Big Bear Solar Observatory (BBSO) in California, equipped with a new technology called Cona, which employs a laser to correct for turbulence in Earth's upper atmosphere.

Related: NASA spacecraft snaps eerie image of eclipsed sun with an extra moon overhead. What's going on?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cona is "like a pumped-up autofocus" for the sky, Nicolas Gorceix, chief observer at BBSO, said in the statement. It's a form of adaptive optics that works by measuring, and then adapting in real-time to, atmospheric distortions, reshaping a special mirror 2,200 times per second.

Turbulence in Earth's upper atmosphere has always been a limiting factor when studying the sun, but Cona increases the resolution of what can be observed, from features over 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) wide to just 63 km (39 miles).

The sun's corona, which means crown, is one of the most mysterious places in the solar system. This outer layer of the sun's atmosphere is blocked from view by the brighter photosphere — the sun's surface — and is only visible briefly to the naked eye during a total solar eclipse. That also applies to prominences, which can be seen during totality as reddish-pink arches and loops.

Despite its tenuous nature, the corona is millions of degrees hotter than the photosphere. It's of critical interest to solar scientists because it's in the corona that the solar wind originates. This constant stream of charged particles then radiates throughout the solar system, interacting with planetary atmospheres (including Earth's) to cause geomagnetic storms and auroras.

Following the successful test of Cona, plans are underway to install it on the 4-meter Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope in Maui, Hawaii, the world's largest solar telescope.

Jamie Carter is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor based in Cardiff, U.K. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners and lectures on astronomy and the natural world. Jamie regularly writes for Space.com, TechRadar.com, Forbes Science, BBC Wildlife magazine and Scientific American, and many others. He edits WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus