Diagnostic dilemma: Weird lump in woman's hip was sponge left behind during C-section

A woman had a swollen and painful hip for years following an emergency cesarean section. When doctors finally took a look, they found something surprising.

The patient: A 38-year-old woman in New Delhi

The symptoms: The patient had given birth via emergency cesarean section in another country, and after the operation, she noted pain on the right side of her lower abdomen. Doctors at the time told her it was normal postoperative pain, and they didn't explore it further. Eventually, a lump formed at the site, and the woman's pain intensified.

What happened next: Four years after her C-section, the patient sought further medical advice at a New Delhi hospital in 2014. Doctors did an ultrasound and CT scan, which revealed a cyst at the site of pain. However, they could not yet tell what lay at the cyst's core. Their first guess was that it was a mesenteric cyst, a type of benign tumor that can cause discomfort and pain.

To confirm this potential diagnosis, they turned to MRI. This created more confusion because it revealed what appeared to be a thick membrane at the core of the mass. Rather than a benign tumor, the doctors now suspected the cyst encased a tapeworm, which could have entered her body if she had eaten food contaminated with tapeworm eggs, for instance.

The treatment: Having failed to identify the contents of the cyst via multiple imaging techniques, the doctors decided to surgically remove the mysterious mass and relieve the woman of her pain. This operation required them to cut off a part of the small intestine, to which the cyst had fused. The patient recovered successfully following this procedure and left the hospital seven days later.

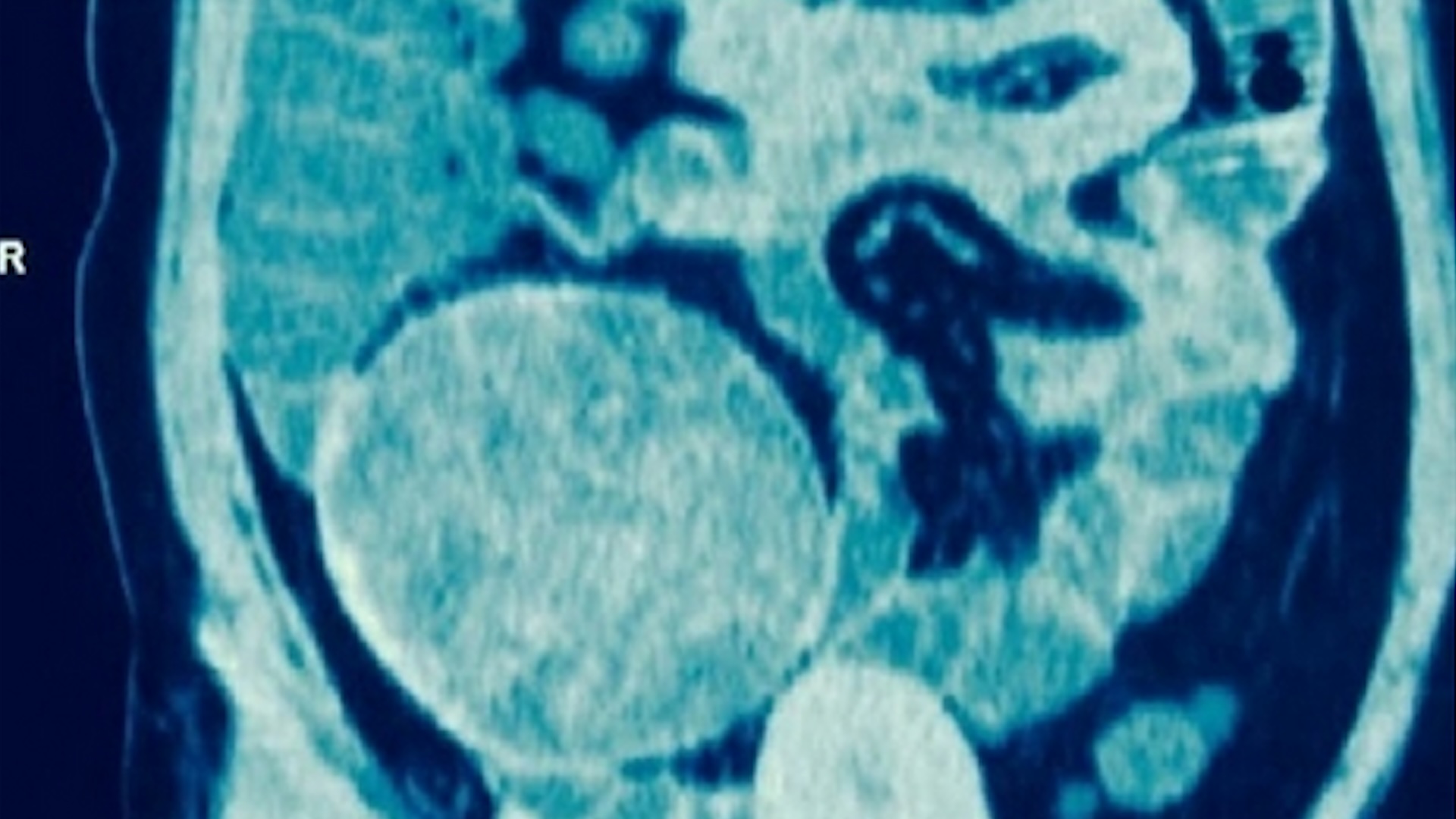

The diagnosis: The cyst measured 8 inches (20 centimeters) long — considerably larger than a typical mesenteric cyst, which is normally no bigger than 2 inches (5 cm) in diameter. Upon opening up the cyst, the doctors discovered a surgical sponge embedded in its center, which they concluded must have been left there accidentally during her C-section.

The cyst, which measured nearly 8 inches long, ensheathed an abandoned surgical sponge (white object) from the patient's previous C-section.

The immune system treats foreign objects in the body as a threat and tries to break them down and remove them. However, because the sponge could not easily disintegrate, the body's defenses instead encased it in a cyst to conceal the potential threat, doctors concluded in a report of the case.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

(Sponges used in surgery should be sterile, so that may help explain the woman's lack of infection; that said, infections and septic shock have occurred in other, similar cases.)

What makes the case unique: Surgeons rarely leave behind a sponge or other object in a patient's abdomen following an operation — a complication known as gossypiboma — but it does happen in about 1 in 1,500 to 1,000 surgeries, estimates suggest.

A simple mistake like this can occur if doctors need to operate in a rush; if surgical teams change partway through the operation; or if the medical staff lose track of how many sponges have been used over the course of a procedure. Sponges are necessary to soak up blood during an operation, but once they turn red, they can blend in with the flesh and become easy to overlook when it is time to close the wound.

Gossypibomas are even harder to detect after the surgery concludes. In this case, the sponge was made of a material that's undetectable on typical scans, so it did not show up with three types of imaging. Following this event, the case report authors recommended that only radio-detectable sponges be used during future surgeries and that the number of sponges present at the start of operation and thrown away are counted to ensure that none go missing inside the body.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Kamal Nahas is a freelance contributor based in Oxford, U.K. His work has appeared in New Scientist, Science and The Scientist, among other outlets, and he mainly covers research on evolution, health and technology. He holds a PhD in pathology from the University of Cambridge and a master's degree in immunology from the University of Oxford. He currently works as a microscopist at the Diamond Light Source, the U.K.'s synchrotron. When he's not writing, you can find him hunting for fossils on the Jurassic Coast.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus