Bottom of the sun becomes visible to humans for the first time in history (photos)

For the first time, scientists have imaged the elusive south pole of the sun. The images captured by the Solar Orbiter spacecraft reveal our star's magnetic field is a powder keg ready to blow.

Just this once, it's OK to stare at the sun — provided you're looking at the European Space Agency's (ESA) newly released, history-making images of the solar south pole.

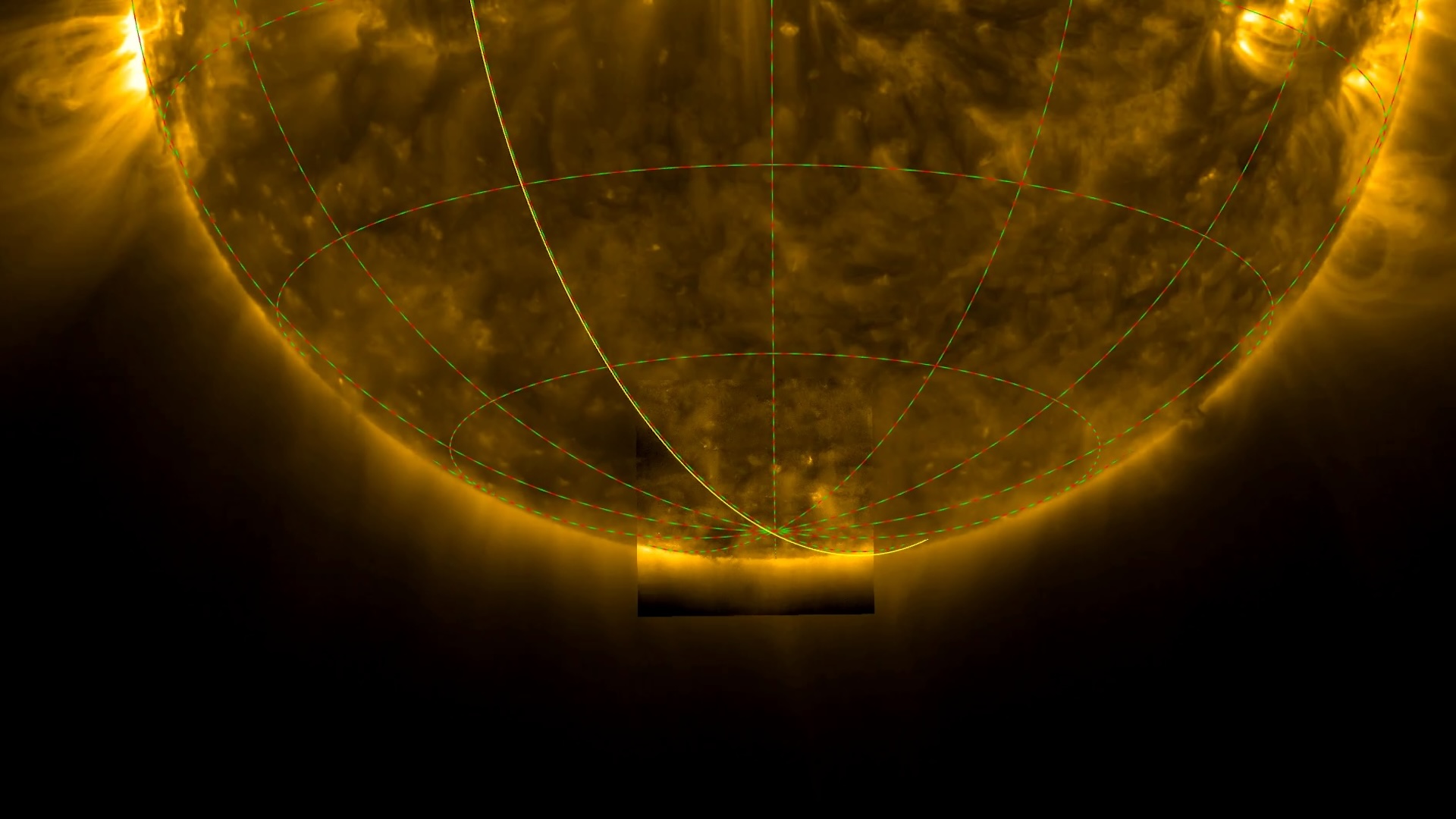

Taken near the sun on March 23 and revealed to Earthlings Wednesday (June 11), the new images from ESA's Solar Orbiter show a view of our star that no human or spacecraft has ever recorded before. While Earth and the other planets orbit relatively in line with the sun's equator on an invisible plane called the ecliptic, Solar Orbiter spent the last several months tilting its orbit to 17 degrees below the solar equator — bringing our star's enigmatic south pole into view for the first time ever.

"Today we reveal humankind's first-ever views of the Sun's pole," Carole Mundell, ESA's director of science, said in a statement. "These new unique views from our Solar Orbiter mission are the beginning of a new era of solar science."

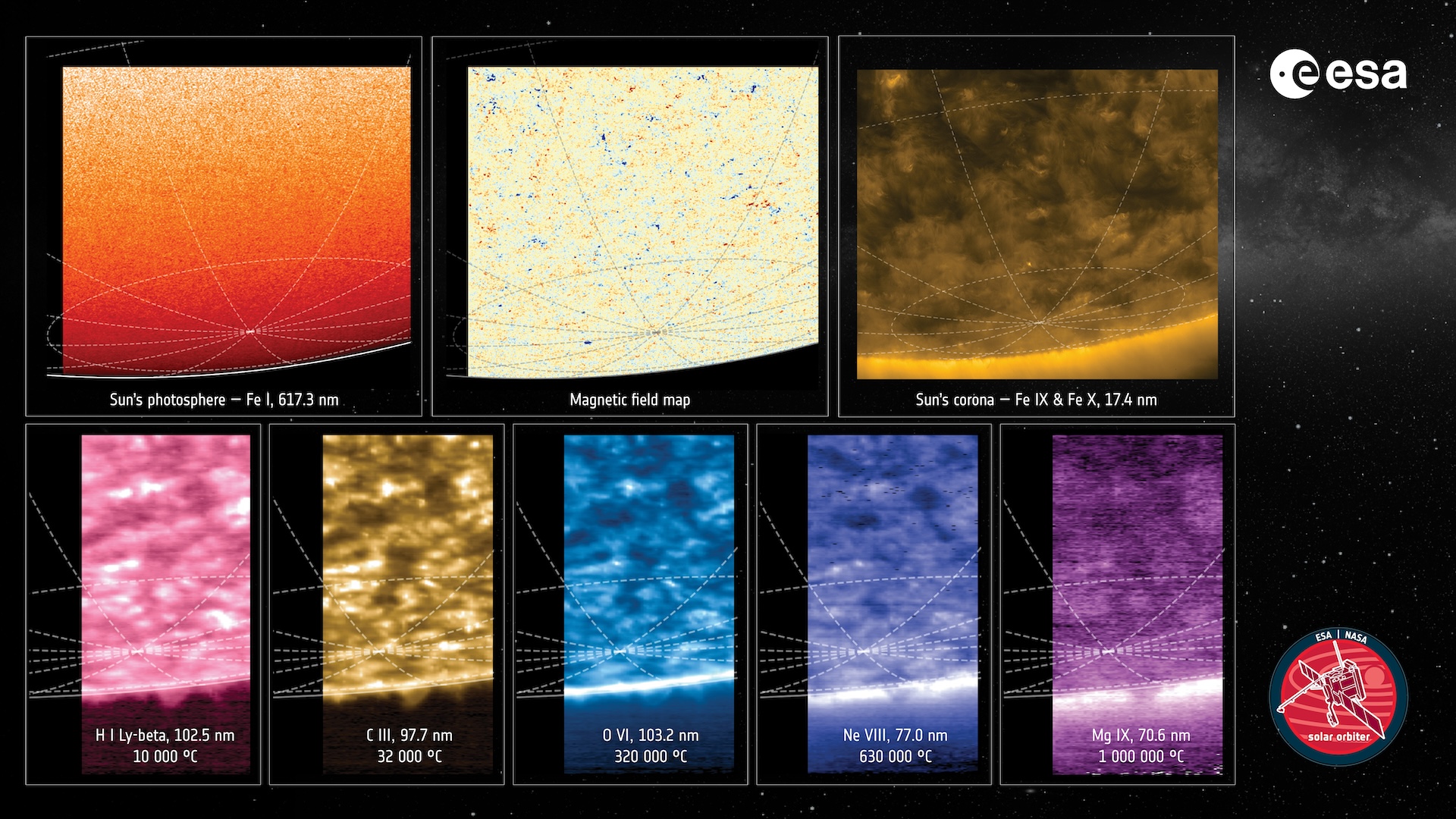

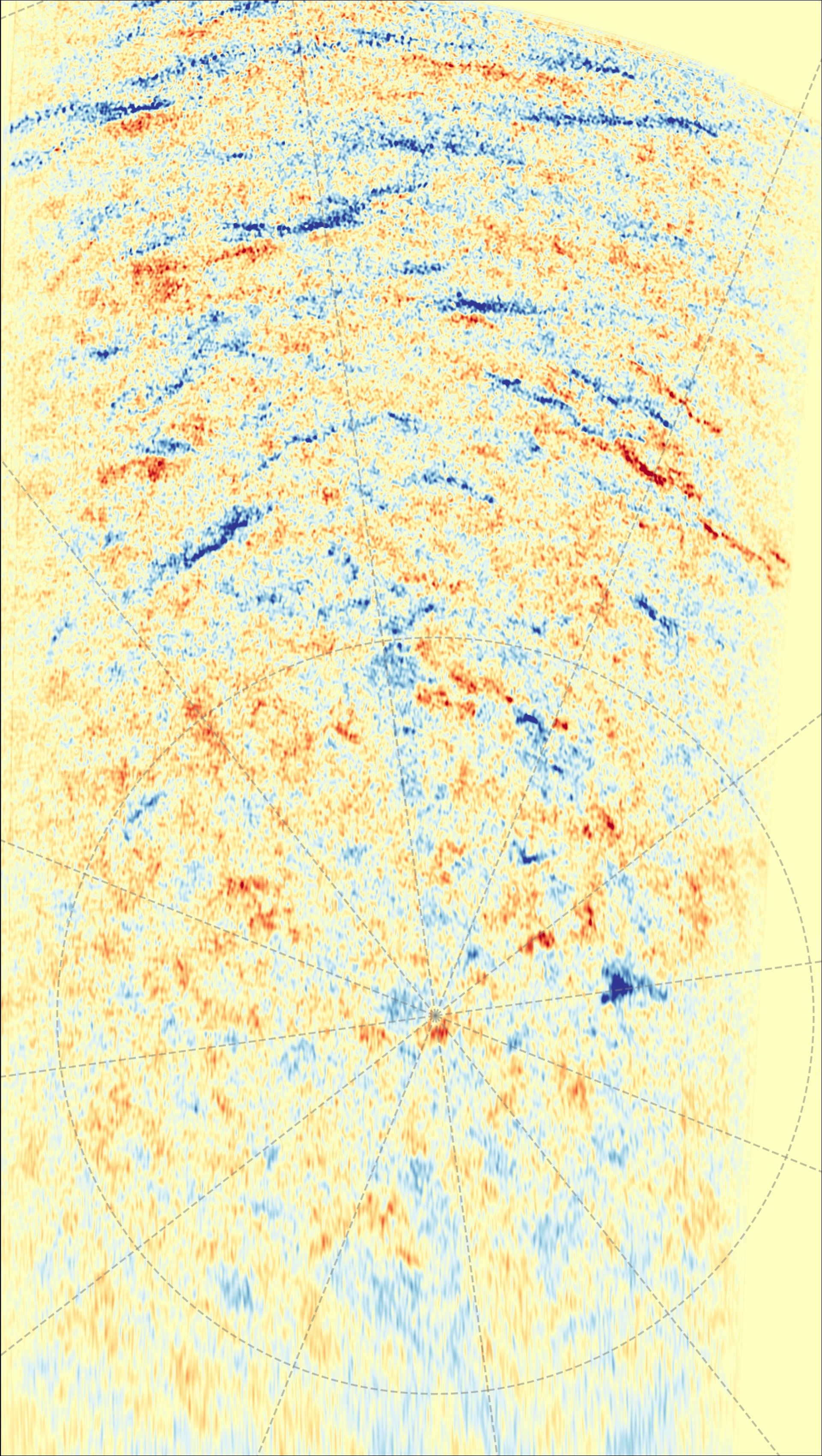

The new images capture the solar pole in a broad swath of visible and ultraviolet wavelengths, using three of Solar Orbiter's 10 onboard instruments. The result is a colorful confetti of solar data, including an unprecedented look at the perplexing tangles of the sun's magnetic field as it prepares to flip, and the high-velocity movements of specific chemical elements as they ride plumes of plasma that make up the solar wind — the constant stream of charged particles that governs space weather throughout our solar system.

These data will help improve our understanding of the solar wind, space weather and the sun's roughly 11-year activity cycle for years to come, according to ESA.

But of particular interest right now, as the sun spits out flares in overdrive during its period of peak activity (called solar maximum), are the magnetic measurements taken with Solar Orbiter's Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) instrument.

Related: NASA spacecraft snaps eerie image of eclipsed sun with an extra moon overhead. What's going on?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

PHI's maps of the solar magnetic field highlight an intriguing paradox: While most magnets have a distinct north and south pole, the sun's south pole is roiling with both north and south polarity magnetic fields (shown as blue and red patches in the corresponding images).

According to ESA, this mess of magnetism is a temporary phenomenon that hints that the sun's magnetic field is about to flip, as it does once every 11 years or so. This magnetic reversal signifies the end of the high-activity solar maximum and begins a transition toward the relative calm of the next solar minimum. When the next minimum begins, approximately five to six years from now, the sun's poles should show only one type of magnetic polarity apiece as our star takes a break from launching violent space weather tantrums.

Solar Orbiter will have several more chances to test these predictions over the coming years. With a little help from the gravitational pull of Venus, Solar Orbiter will continue tilting its orbit further from the solar equator, reaching a tilt of 24 degrees in December 2026 and a whopping 33 degrees in June 2029. These ever-more-angular vantage points will expose the solar poles in even greater detail, improving our knowledge of our home star with every flyby.

"This is just the first step of Solar Orbiter's 'stairway to heaven'," Daniel Müller, ESA's Solar Orbiter project scientist, said in the statement. "These data will transform our understanding of the Sun's magnetic field, the solar wind, and solar activity."

Update: This article was updated at 9:30 a.m. ET on June 12 to alter the headline

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus