'Cannibal' coronal mass ejection that devoured 'dark eruption' from sun will smash into Earth today (July 18)

Two coronal mass ejections have combined into an enormous cloud of magnetized plasma that is forecast to hit Earth on Tuesday and potentially trigger a weak geomagnetic storm.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A "cannibal" coronal mass ejection (CME) birthed from multiple solar storms, including a surprise "dark eruption," is currently on a collision course with Earth and could trigger a weak geomagnetic storm on our planet when it hits on Tuesday (July 18).

CMEs are large, fast-moving clouds of magnetized plasma and solar radiation that occasionally get flung into space alongside solar flares — powerful explosions on the sun's surface that are triggered when horseshoe-shaped loops of plasma located near sunspots snap in half like an overstretched elastic band. If CMEs smash into Earth, they can cause geomagnetic storms — disturbances in our planet's magnetic field — that can trigger partial radio blackouts and produce vibrant aurora displays much farther away from Earth's magnetic poles than normal.

A cannibal CME is created when an initial CME is followed by a second faster one. When the second CME catches up to the first cloud, it engulfs it, creating a single, massive wave of plasma.

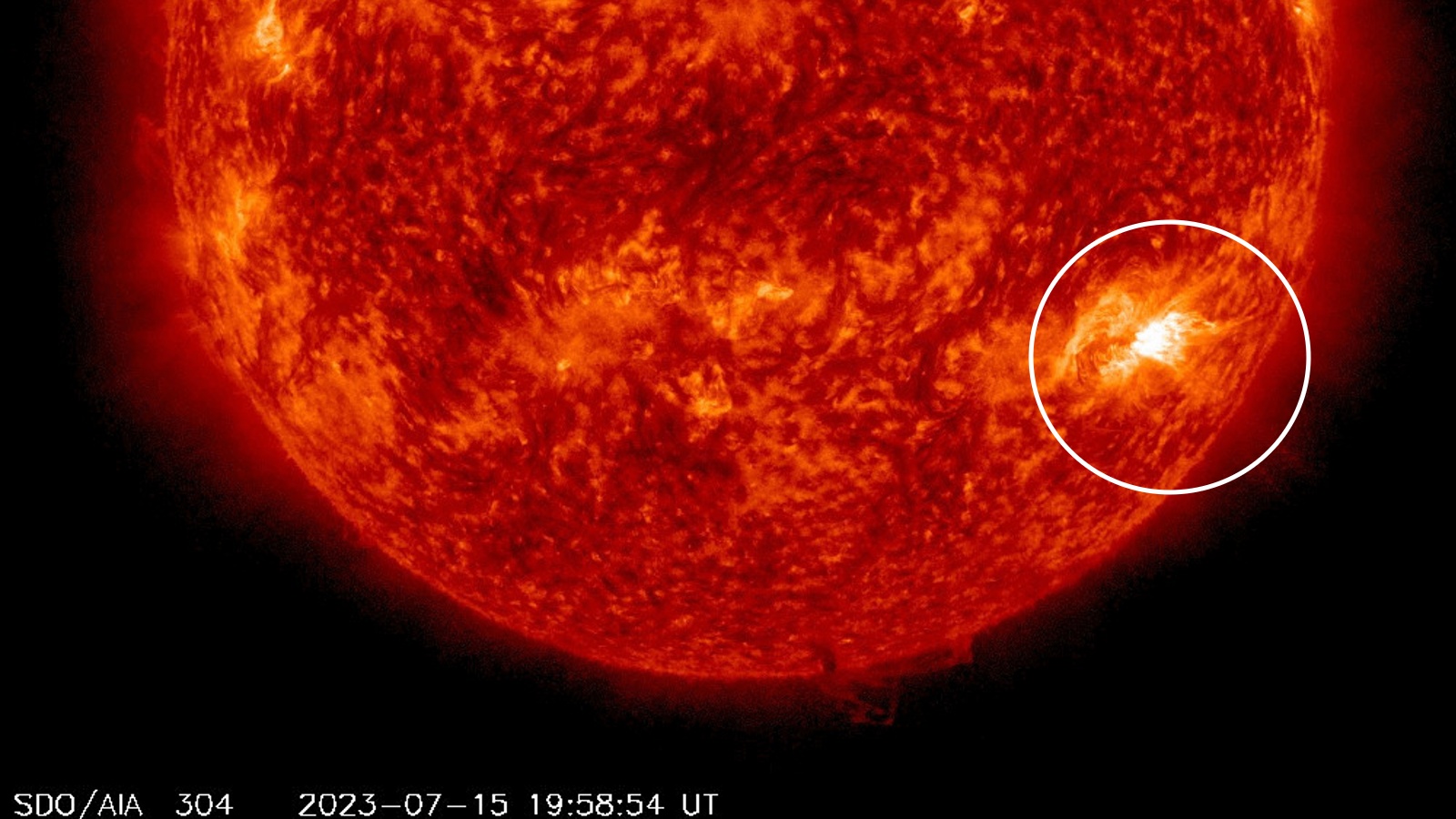

On July 14, the sun launched a CME alongside a dark eruption — a solar flare containing unusually cool plasma that makes it look like a dark wave compared to the rest of the sun's fiery surface — from sunspot AR3370, a small dark patch that until then had gone largely unnoticed, according to Spaceweather.com. On July 15, a second, faster CME was launched from the much larger sunspot AR3363.

A simulation from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Space Weather Prediction Center showed that the second storm will catch up with the first CME and form a cannibalistic cloud, with a strong likelihood of it hitting Earth on July 18.

Related: 10 signs the sun is gearing up for its explosive peak — the solar maximum

Both CMEs came from C-class solar flares, the mid-tier of solar eruption strength. Their combined size and speed mean they are likely to trigger a G1 or G2 level disturbance, the two lowest classes for a geomagnetic storm.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cannibal CMEs are rare because they require successive CMEs that are perfectly aligned and traveling at specific speeds. But there have been several in the last few years.

In November 2021, a cannibal CME smashed into Earth, triggering one of the first major geomagnetic storms of the current solar cycle. Two more CMEs slammed into our planet in 2022, the first in March and another in August, and both triggered strong G3-class storms.

Cannibal CMEs become more likely during the solar maximum, the chaotic peak of the sun's roughly 11-year solar cycle. During this time, the number of sunspots and solar flares increases sharply as the sun's magnetic field becomes increasingly unstable.

Scientists initially predicted that the next solar maximum would arrive in 2025 and be weak compared to past solar cycles. But Live Science recently reported that the sun's explosive peak could arrive sooner — and be more powerful — than previously expected. Weird solar phenomena, such as cannibal CMEs, further indicates the solar maximum is fast approaching.

Earth has already been hit by five major (G4 or G5) geomagnetic storms this year, including the most powerful storm for more than six years. These storms have superheated the thermosphere — the second-highest layer of Earth's atmosphere — to its highest temperature in more than 20 years.

The number of sunspots is also increasing as we approach solar maximum, reaching its highest total for almost 21 years in June.

Editor's note: This story was updated at 03:30 ET to correct an error about the scale used to measure geomagnetic storms.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus