15 signs the sun is gearing up for its explosive peak — the solar maximum

Experts believe the upcoming solar maximum could be more active and arrive sooner than previously expected. Here are 15 signs that they are right.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

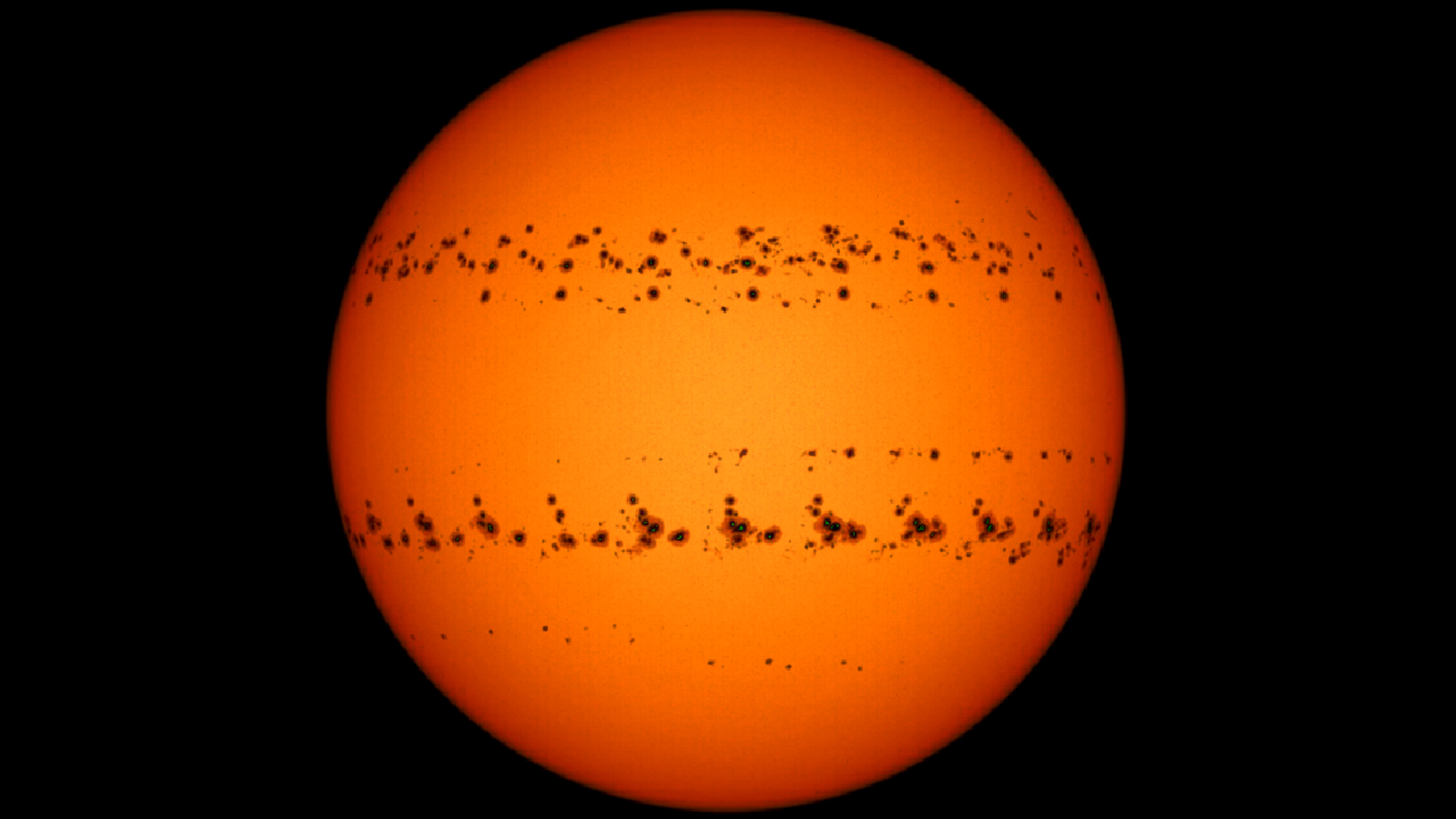

Roughly every 11 years, the sun slowly transitions from solar minimum, when our star is a smooth and calm ball of plasma, to solar maximum, when it becomes a chaotic, fiery mass littered with dark, planet-size sunspots that spew out solar storms.

During solar maximum, the likelihood of Earth being bombarded by these stellar storms goes up dramatically. And such solar storms can mess with radio signals, power infrastructure, space missions and satellites in low-Earth orbit.

Scientists initially believed the next solar maximum would likely arrive sometime in 2025 and that the peak in solar activity would be just as underwhelming as the last, below-average solar maximum.

Article continues belowBut in an explosive twist, experts revealed to Live Science that the solar maximum could likely arrive sooner and be more powerful than previously forecast. And on Oct. 25, NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center released an "updated prediction" for Solar Cycle 25, which confirms that these experts were correct.

From rising sunspot numbers to bizarre plasma structures and enormous solar storms, here are 15 signs the solar maximum is closer than you think.

Rising sunspot numbers

The main way scientists track solar cycle progression is by counting the number of sunspots on our home star's surface. These dark patches are a sign that the sun's magnetic field is getting tangled, which ramps up solar activity.

But since the current solar cycle began, the number of visible sunspots on the sun has far exceeded the number predicted by initial forecasts from scientists at NASA and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The observed number of sunspots has outpaced predictions for 30 months in a row. The first major sunspot spike occurred in December 2022, when the sun reached an eight-year sunspot peak. And in June this year, the sunspot number reached its highest value since September 2002, more than 20 years ago.

X-class flare frequency

Solar flares are bright flashes of light and radiation launched from sunspots. Sometimes they're accompanied by enormous, magnetized clouds of fast-moving particles, known as coronal mass ejections (CMEs). The most powerful solar flares are X-class flares, which are the least common type, followed by M-class and C-class blasts: All three happen more often during a solar maximum.

The number of X-class flares is on the rise. There have already been 11 of these enormous flares in 2023, including a surprise X-class flare from the sun's far side in January, and another in February that launched a CME directly at Earth, triggering radio blackouts. In comparison, there were only seven X-class flares in the whole of 2022 and two in 2021.

The total number of X-class, M-class and C-class flares has also spiked: In 2021, there were around 400 of these flares; in 2021, there were around 2,200; and so far in 2023, there have already been around 2,600, according to SpaceWeatherLive.com.

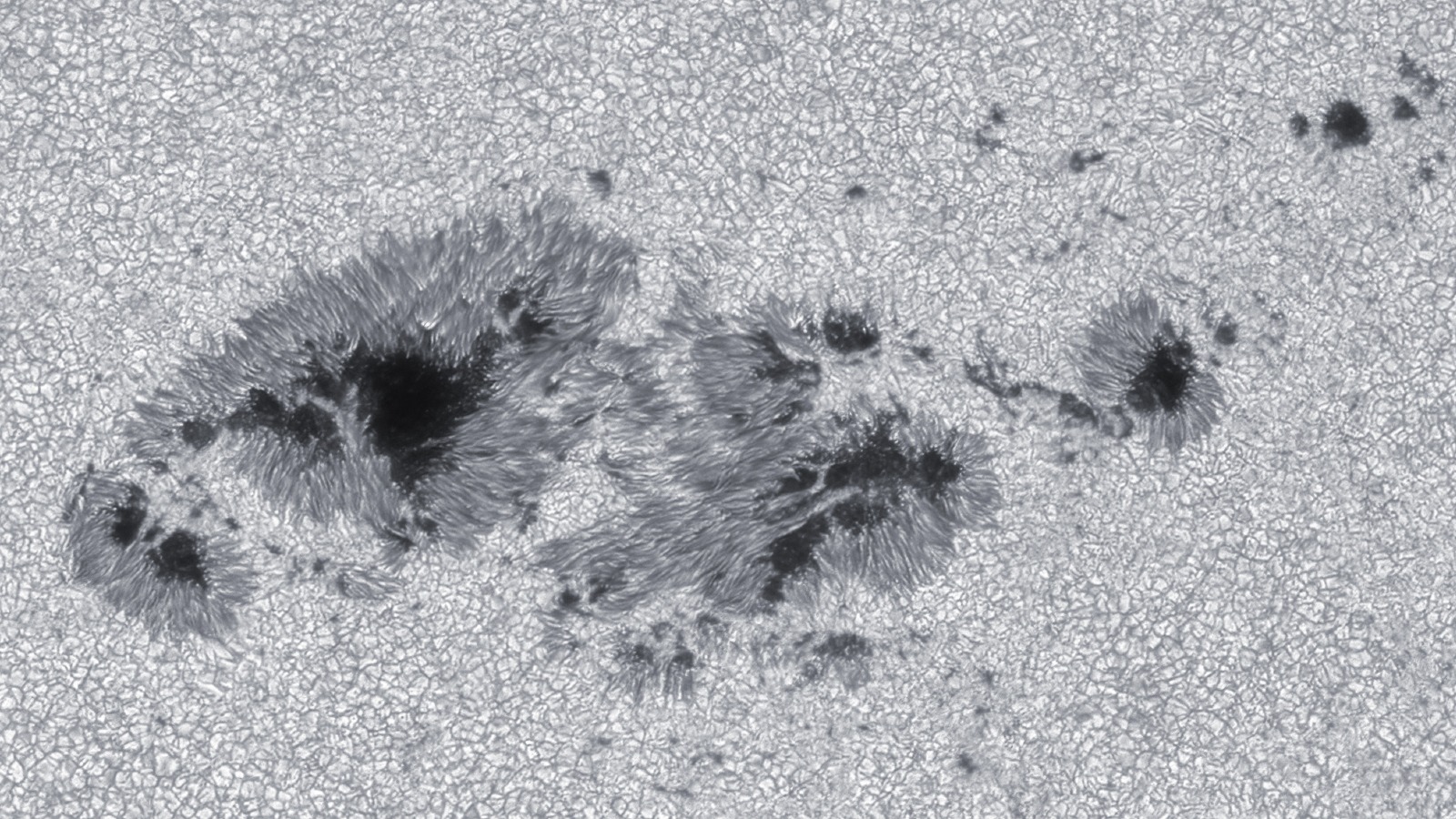

Gigantic sunspot

During the build-up to solar maximum, not only do sunspots become more common but they also start to grow much larger.

On June 27 of this year, a dark patch, named AR3354, emerged on the solar surface, and within 48 hours, the sunspot's surface area had swelled to 1.35 billion square miles (3.5 billion square kilometers), or 10 times wider than Earth.

After growing to its full size, AR3354 unleashed several large solar flares, including an X-class flare that launched a CME, directly at Earth, which later caused a short radio blackout and auroras when it slammed into our planet's magnetic shield, or magnetosphere.

Eerie airglow

One of the most visually stunning indicators that solar maximum is approaching is a rare aurora-like phenomenon known as airglow.

Unlike auroras, which form when highly energetic particles from CMEs or solar wind penetrate Earth's magnetosphere and excite gas molecules in the upper atmosphere, airglow is produced by more gradual solar radiation, which becomes more intense in the lead-up to solar maximum.

During the day, this radiation slowly ionizes or strips electrons from gas molecules in the upper reaches of the atmosphere. But at night, the molecules regain their lost particles and emit light as they do so, which creates slow-moving rivers of green and red light in the sky.

By June, the number of airglow sightings began to increase and remained high in the following months.

Disappearing clouds

While airglow has become more common in the night skies, another much-anticipated phenomenon has dwindled thanks to rising solar activity.

Noctilucent, or night-shining, clouds (NLCs) are made from atmospheric water vapor that freezes into ice crystals. The crystals stick to particles of volcanic and meteor dust in the mesosphere — the third layer of Earth's atmosphere. These crystal clouds continue to reflect sunlight shortly after sunset, which makes them shine in the night sky.

The best time to see these shimmering clouds is between June and August. But this year, there were barely any NLC sightings because increased levels of solar radiation warmed the mesosphere, meaning there is less water vapor available to form the colorful clouds.

Cannibal CMEs

As the number of CMEs firing out of the sun increases, so too does the chance of a rare type of solar storm known as a "cannibal CME."

Cannibal CMEs are created when one CME catches up to and engulfs another CME that was unleashed shortly beforehand, resulting in one massive cloud of magnetized plasma. As these cannibalistic storms require successive CMEs to form, they become much more common in the build up to solar maximum.

Before this year, three cannibal CMEs had recently slammed into Earth — the first erupted in November 2021, the second in March 2022 and the third in August the same year. But in July, the sun released the most extreme version of these conjoined solar storms when a massive CME devoured an unusual plume of "dark plasma" before smashing into our planet.

Detecting solar storms on Mars

As the sun begins to wake up from its cosmic nap, its rising activity levels also start to become more noticeable beyond Earth.

So far, sensors on the Red Planet have detected two major solar storms: A massive CME that exploded from the sun in October 2021, which was also detected simultaneously on Earth and the moon; and a "mystery explosion" from a far side sunspot that launched a CME at Mars and triggered Martian auroras.

Scientists have also started using NASA's Perseverance rover to keep an eye on the far side of the sun to search for large sunspots that could spawn potentially solar storms that may pose a threat to Earth and we would not otherwise see coming.

Geomagnetic storm bombardment

A geomagnetic storm is a disruption to Earth's magnetic field caused by CMEs or solar wind bashing into the upper atmosphere. These storms often trigger vibrant aurora displays.

Geomagnetic storms come in four classes, from the weakest, G1, up to the most severe, G4. G3 and G4 storms can cause radio blackouts that blanket half of the planet for several hours and cause problems for satellites in low-Earth orbit.

So far in 2023, two G3 storms and three G4 storms have bombarded Earth. For context, there were only two G3 storms and no G4 storms in 2022 and only one of each in 2021, according to SpaceWeatherLive.com.

One of the 2023 storms, which occurred on March 24, was the most powerful geomagnetic storm to hit Earth in more than six years and triggered auroras across more than 30 U.S. states, as well as unusual optical phenomena including the aurora-like phenomena STEVE in the U.S. and a blood red arc, known as a stable auroral red arc (SAR), in Denmark.

Thermosphere temperatures rising

The increase in geomagnetic storms has also caused temperatures to sharply climb in the thermosphere — the second highest layer in the atmosphere.

Molecules of gas in the thermosphere absorb a storm's excess energy, then emit that energy as infrared radiation, cooling the thermosphere back down. But this year, because the storms are coming back to back, the gas has not had a chance to cool, experts told Live Science.

The thermosphere naturally warms and cools in conjunction with the solar cycle. But the peak temperature, which occurred in March, was the highest for almost 20 years. This is a strong sign that the current solar cycle is more active than the previous one.

As the thermosphere warms it also expands, which can create additional drag for satellites in low-Earth orbit and pull them out of position. That increases the odds of satellites colliding or falling out of orbit during the solar maximum.

Surprising solar eclipse image

On April 20, a rare "hybrid eclipse" occurred in the sky above Australia, which provided observers with a chance to look at the sun's corona, the outermost part of the star's atmosphere, poking out from behind the moon in the darkened sky.

During the eclipse, a group of photographers created a stunning composite image composed of hundreds of shots of the event. Their image shows the ghostly filaments of the corona, which were much larger than they expected. This is another sign that the sun is closer to solar maximum than initially thought.

To further highlight the sun's restless state, the star also happened to belch out a large CME as the eclipse was taking place, which is clearly visible in the image.

Towering solar tornado

As the sun's magnetic field becomes more tangled and unstable, the star's plasma also becomes less constrained to the surface and can often erupt without warning.

In March, such plasma fueled a gigantic "solar tornado" the size of 14 Earths stacked on top of each other that raged on the sun's surface for three days. The spinning cone formed when a horseshoe-shaped loop of plasma got caught in a rapidly rotating magnetic field.

At its peak, the fiery twister reached 111,000 miles (178,000 kilometers) above the sun's surface, which is around double the average size of previously observed solar tornados.

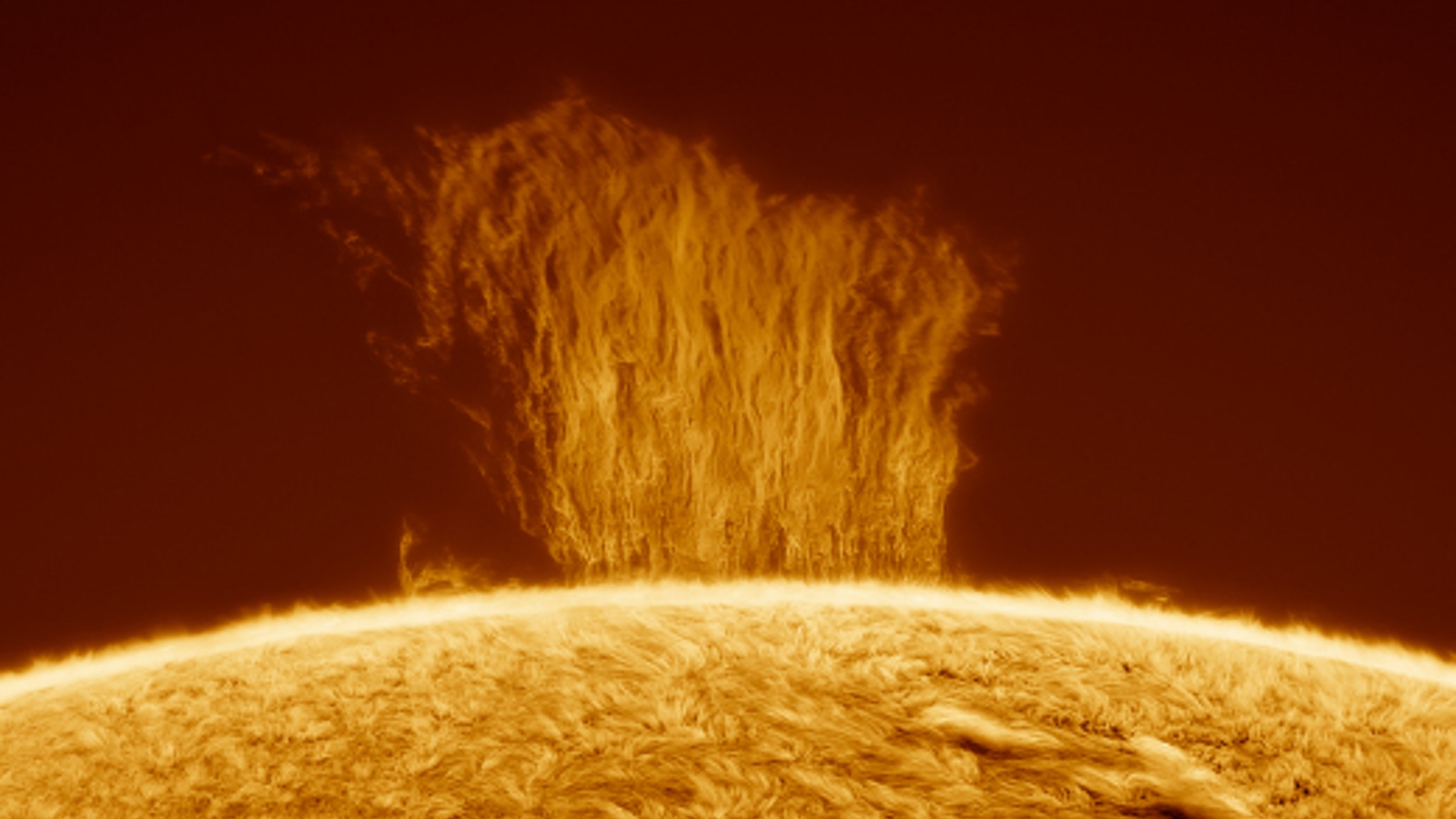

Fiery plasma waterfall

Scientists recently spotted another unusual sight on the sun's surface: a "plasma waterfall," also known as a polar crown prominence (PCP), which rose above the surface of the sun on March 9 before raining plasma back onto the star.

PCPs are mini eruptions that get trapped by the sun's magnetic field and pulled back toward the solar surface before they can escape into space. These rare waterfalls only form near the sun's magnetic poles, where the star's magnetic field is strongest.

At its peak, the PCP reached 62,000 miles (100,000 km) above the sun's surface, which is the equivalent of eight Earths stacked on top of each other.

Enormous polar vortex

Continuing the trend of bizarre plasma phenomena, on Feb. 2, a gigantic halo of rapidly rotating plasma, dubbed a "polar vortex," swirled around the sun's north pole for around eight hours.

The never-before-seen vortex was created when a massive tentacle of plasma snapped apart in the sun's atmosphere and fell back toward the sun, similar to how a PCP forms. But scientists don't know exactly why the plasma stayed above the sun's surface for so long.

At the time, experts noted that weird plasma events like this tend to happen around a solar maximum.

Butterfly CME

The number of CMEs shooting out of the sun has increased alongside the rise in the number of solar flares. But one of the most visually striking examples was an enormous "butterfly" CME that erupted on March 10.

The "butterfly wings" appeared because the CME exploded on the sun's far side, meaning a large proportion of the blast was out of view. As a result, experts are unsure how powerful the blast really was.

Luckily, the CME was pointed away from Earth. However, experts predicted that the cosmic cloud may have bashed into Mercury and potentially sheared off dust and gas from the closest planet to the sun because of its weak magnetic field.

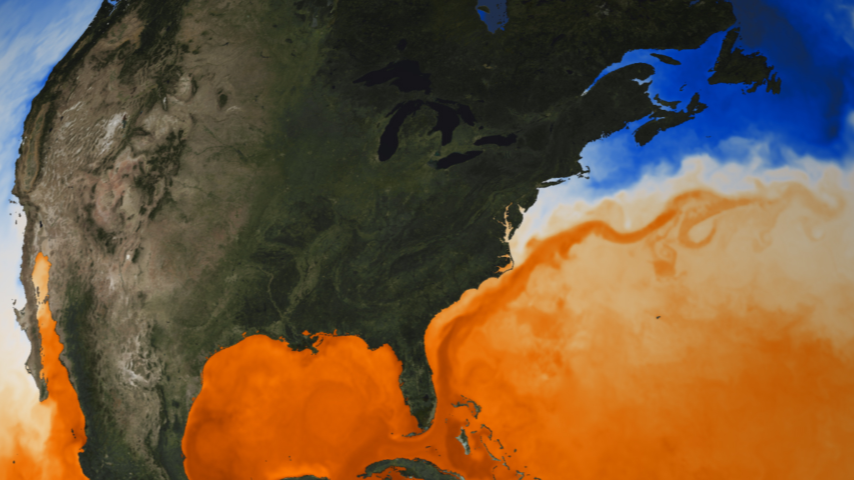

1 million-mile-long plasma plume

One of the earliest signs that solar activity was beginning to ramp up was a gigantic plume of plasma that launched into space following a CME in September 2022.

Astrophotographer Andrew McCarthy captured the plume in a stunningly detailed composite image that merged hundreds of thousands of individual shots. The enormous fiery column reached around 1 million miles (1.6 million km) above the sun's surface and traveled at a speed of around 100,000 mph (161,000 km/h).

"We'll see more of these as we head further into solar maximum," McCarthy told Live Science at the time. The plasma plumes are also likely to get "progressively larger," he added.

To find out more about the upcoming solar maximum and how it might impact Earth, check out solar maximum feature.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus