'Mystery explosion' on sun launches coronal mass ejection at Mars

The sun has launched a surprise CME directly at Mars, which could spark auroras and damage the Red Planet's atmosphere when it hits on Sept. 1.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

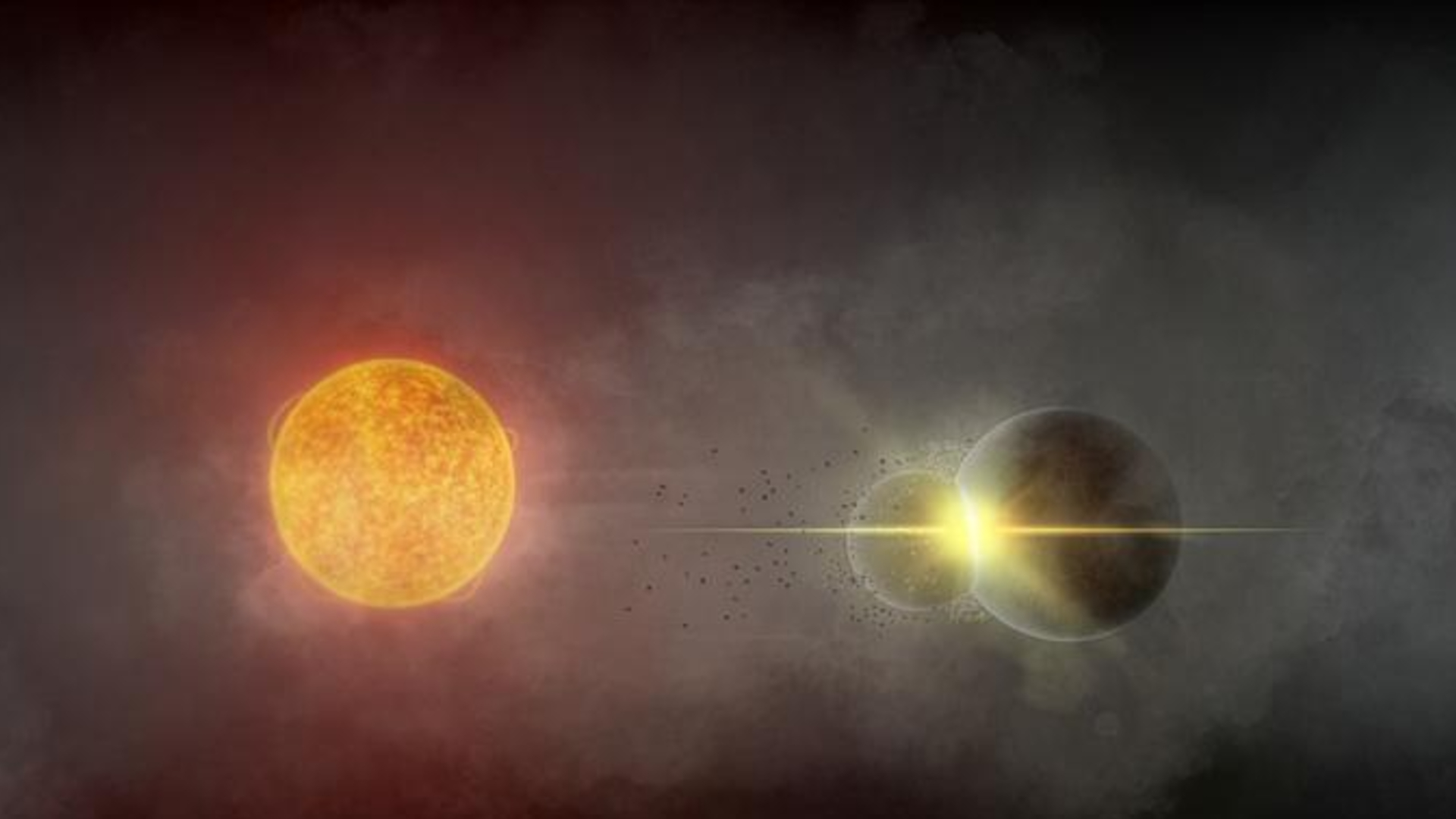

A mysterious explosion on the sun's far side has launched a blob of plasma and radiation that is forecast to slam into Mars. If the solar storm hits the Red Planet, it could trigger faint ultraviolet auroras and potentially erode part of the Martian atmosphere, according to experts.

Earth-orbiting satellites detected the surprise explosion on Aug. 26 on the far side of the sun. Further analysis revealed the explosion was an M-class solar flare, the second most powerful type of solar eruption. However, researchers are still unsure what triggered the explosion as there were no prior signs of sunspots — dark, highly magnetized patches on the sun's surface that solar flares are launched from — near where the blast originated, according to Spaceweather.com.

Solar flares can occasionally launch coronal mass ejections (CME) — fast-moving clouds of magnetized plasma and radiation — into space. Researchers detected a CME in the wake of the M-class flare but didn't closely monitor it because it posed no threat to Earth. But in the last few days, scientists have realized the CME will likely hit Mars on Sept. 1.

Article continues belowThe CME could create auroras over the Red Planet if it hits, according to Spaceweather.com, although they will appear faint.

Related: Massive solar explosion felt on Earth, the moon and Mars simultaneously for the 1st time ever

On Earth, auroras occur when radiation from solar storms or solar wind is absorbed by gas in the upper atmosphere, which excites the molecules and causes them to release energy in the form of light. This usually only happens near Earth's poles where our planet's magnetosphere, or protective magnetic field, is weakest.

But Mars has a very thin atmosphere, with around 100 times less gas than Earth's, so its auroral displays are very weak in comparison and usually only show up in ultraviolet wavelengths. The Red Planet also lacks a proper magnetosphere because of its geologically dead core, meaning the planet is instead covered by patchy, mushroom-shaped magnetic fields. As a result, Martian auroras can appear almost anywhere on the planet, according to NASA. Because of the planet's weak magnetic shielding, major CMEs could further strip away the planet's faint atmosphere, according to Spaceweather.com.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists have spotted major auroras on Mars at least three times. In 2022, the United Arab Emirates Mars Mission's Hope orbiter spotted bizarre, worm-like auroras zigzagging across the planet. In 2014, NASA's Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) spacecraft detected auroras in Mars' northern hemisphere, and in 2004, the European Space Agency's Mars Express spacecraft spotted auroras in the planet's southern hemisphere, according to NASA.

However, research from 2019 suggests that Mars may have much more frequent and faint auroras, known as proton auroras, that are triggered by solar wind.

Major Martian auroras could become more likely over the next few years as the sun enters the solar maximum — the most active phase of the sun's roughly 11-year solar cycle, when the number of sunspots increases and solar flares become more common. The solar maximum was originally forecast to begin sometime in 2025, but in June, Live Science reported that the solar maximum could arrive sooner and be more powerful than originally expected, possibly arriving by the end of 2023 or early 2024.

NASA's Perseverance Mars rover has spent the last few months spying on the sun's far side in search of big sunspots that could pose a risk to Earth. But the rover failed to see the mysterious explosion that launched the latest CME directly toward Mars.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus