See the first clear images of 'sun rays' on Mars in eerie new NASA photos

The rays appear when sunlight shines through gaps in the cloud during sunrise or sunset and have never been seen this clearly on the Red Planet before.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

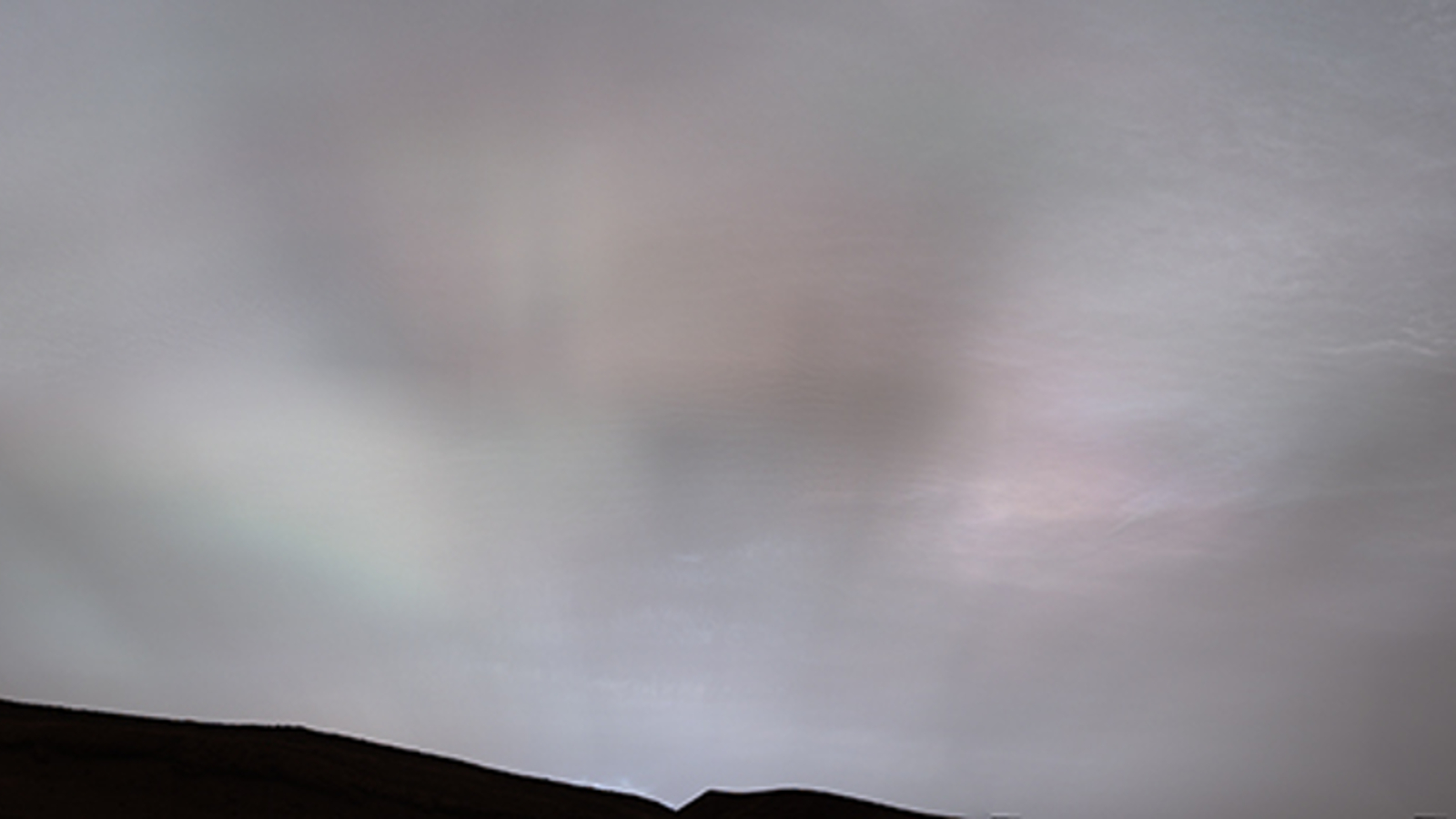

NASA's Curiosity rover recently snapped a stunning shot of dazzling "sun rays" shining through unusually high clouds during a Martian sunset. It is the first time sun rays have been clearly visible on the Red Planet.

Curiosity captured the new image on Feb. 2 as part of a series of twilight cloud surveys that have been ongoing since January and will end in mid March. The photo, which is a panorama comprising 28 individual images, was shared by the Curiosity rover's Twitter page on March 6.

"It was the first time sun rays have been so clearly viewed on Mars," team members from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) wrote in a statement.

Sun rays, also known as crepuscular rays, occur when sunlight shines through gaps in the clouds during sunsets or sunrises when the sun is below the horizon. The rays are most visible on Earth in hazy conditions, when the light scatters off smoke, dust and other particles in the atmosphere, according to the U.K. Met Office. Although the dazzling beams appear to converge at a point beyond the cloud, they actually run near-parallel to one another.

Martian clouds, which are mostly made from ice crystals of both water and carbon dioxide, normally hover no more than 37 miles (60 kilometers) above the ground. But the clouds in the new image are estimated to be much higher, which is likely why this unusual phenomenon became visible to the rover, JPL representatives wrote.

Related: Detecting life on Mars may be 'impossible' with current NASA rovers, new study warns

On Earth, sun rays normally appear red or yellow because the sunlight passes through around 40 times more air than it does when shining directly from above at midday, according to the Met Office. This means more light gets scattered by the air, known as Rayleigh scattering. As the light scatters, longer wavelengths of light that produce colors such as blue and green get scattered the most, so the light that reaches our eyes appears predominantly yellow and red.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

On Mars, the sun rays have a much more white color because the Red Planet has a very thin atmosphere, which means sunlight doesn't scatter as much as on Earth. This is why Martian sunsets often have a blue-ish glow.

On Jan. 27, Curiosity also snapped a picture of a "feather-shaped iridescent cloud" during another one of its twilight cloud surveys. This was similar to a series of rainbow-colored clouds that recently shone in the skies above the Arctic. The rainbow clouds, known as polar stratospheric clouds, only form on Earth during unusually cold conditions when clouds form at higher altitudes than normal, which enables them to scatter strong sunlight as the surrounding skies darken. This suggests that Mars' clouds remained unusually high in the time period between the two photos being taken.

Spotting strangely colored clouds and sunsets helps planetary scientists learn exactly what the clouds are made of and understand more about Mars' limited atmosphere.

"By looking at color transitions, we're seeing particle size changing across the cloud," Mark Lemmon, an atmospheric scientist at Space Science Institute who has worked on the Curiosity rover, said in the statement. "That tells us about the way the cloud is evolving and how its particles are changing size over time."

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus