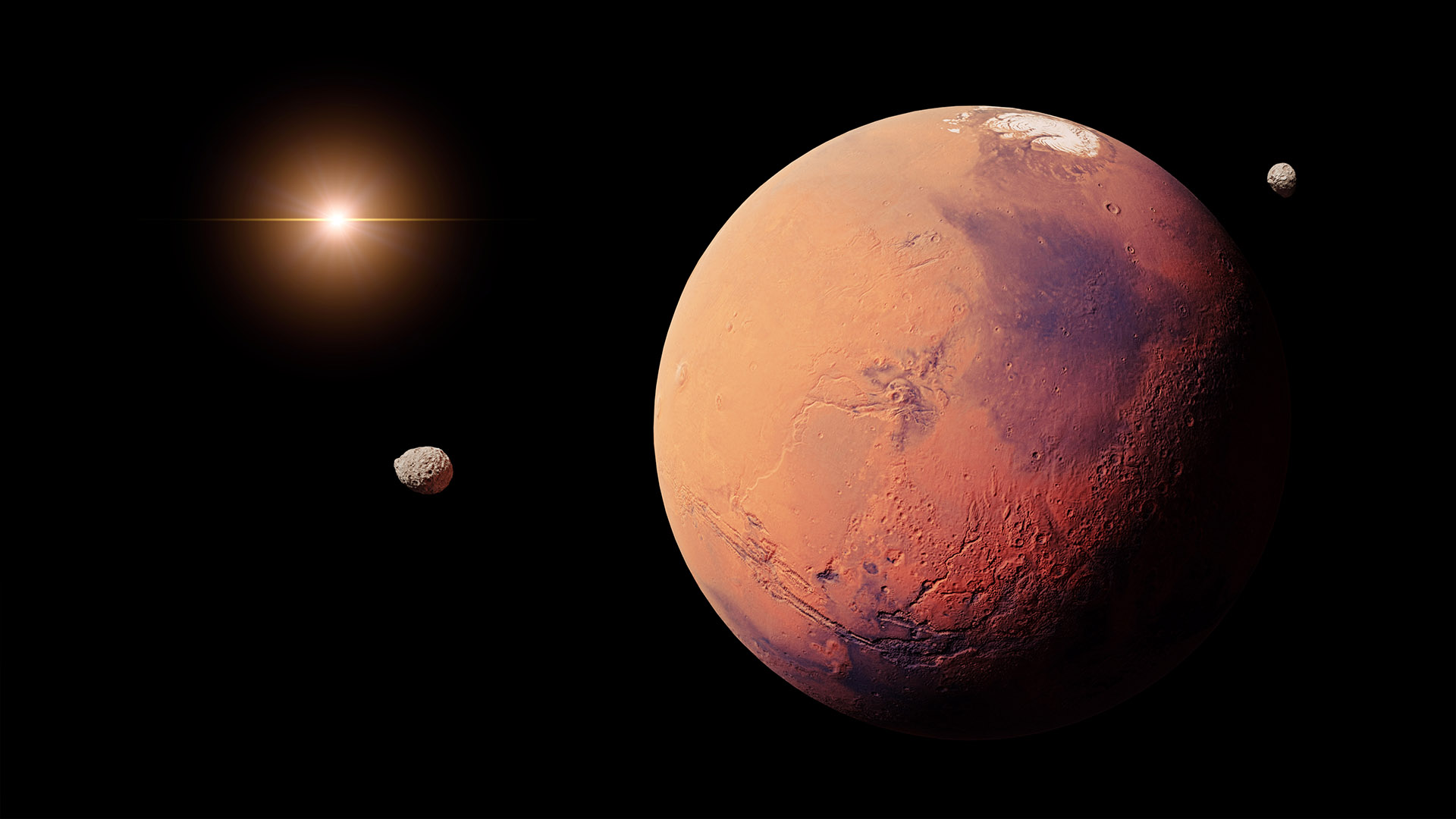

Just 22 people are needed to colonize Mars — as long as they are the right personality type, study claims

Researchers estimated that as few as 22 people would be needed to sustain a colony on Mars. But there are lots of caveats, and the new study largely misses the point of colonizing the Red Planet in the first place, experts say.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Only 22 people are needed to create a colony on Mars, an optimistic new study suggests. However, not everyone agrees, and some experts think many more people would be needed to create a lasting human presence on the Red Planet.

In the study, which was uploaded to the pre-print database arXiv on Aug. 11 and has not been peer-reviewed, researchers used a computer program, known as an agent-based model (ABM), to predict how many people would be needed to sustain a colony on Mars. ABMs simulate how well groups react to challenging scenarios based on their personality types.

The model looked at four personality types: agreeables, who are not very competitive or aggressive; socials, who are extroverted and do well in social settings; reactives, who struggle to deal with changes to routine; and neurotics, who are highly competitive and aggressive. The model then varied the number of each type when doing key tasks such as Martian mining and farming.

The researchers found that iIf most people were agreeables or socials, just 22 people could sustain a colony. With more neurotics and reactives, larger groups were needed to succeed.

Limiting the size of the first Martian colonies will be very important, because the more people and equipment that are needed, the more expensive it will be.

Related: How long will it take for humans to colonize Mars?

However, the study has major limitations. For example, the model assumed that someone else had built the colony's infrastructure, such as buildings, vehicles and other equipment. The first colonists were also assumed to have seven years' worth of energy from a mini nuclear reactor, like the ones that power the Mars rovers, and to receive regular supplies from Earth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The model also only simulated the first 28 years of the colony. Models were deemed a success as long as at least 10 people survived to the mission's end.

As a result, not everyone is convinced that a colony with so few people would work out in reality, especially if the end goal is creating a self-sustaining civilization on the Red Planet.

"Twenty-two people is not enough to build and sustain a fully functioning and autonomous colony on Mars," Jean-Marc Salotti, an astronautics researcher at the IMS (integration from material to systems) laboratory in Bordeaux, France, told Live Science. Salotti's research had previously found the minimum to be 110 people.

Just 22 people may survive on the planet for a limited time — as long as they have the necessary infrastructure, energy and resources — but they would not thrive, he added.

And while the new study's idea of factoring in personality types was a smart move, it also has its limitations, Salotti said.

"For a colony, a simple dispute or conflict could lead to a disaster," Salotti said. But the four personality types used in the study are "oversimplified, he added. Building and sustaining an autonomous colony on Mars requires more people with a greater range of knowledge and skills to overcome the challenges they would face, Salotti said. So he stands by his minimum estimate of 110 for future missions.

A long-term Martian colony would also require a much larger gene pool than 22 people, Salotti said. If not, Martian babies would run into problems with inbreeding, which would reduce resilience and increase the odds of a disease or physiological defect wiping them out.

In a 2018 paper, also uploaded to arXiv, researchers calculated that producing a genetically viable human population on a one-way trip to Proxima Centauri, the nearest star system, would require at least 98 people. A similar number would be needed on Mars, Salotti said.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus