Giant sunspot grew 10 times wider than Earth in just 48 hours, then spat X-class flare right at us

The enormous dark patch and its powerful eruption are both signs that the solar maximum is fast approaching — and could be more active than expected.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

An enormous, rapidly growing sunspot on the sun's surface has unleashed a mighty X-class flare — the most powerful type of solar flare the sun is capable of producing. The solar storm slammed into our planet, triggering brief radio blackouts in parts of the U.S. and elsewhere, but it could have been a lot worse, experts warned.

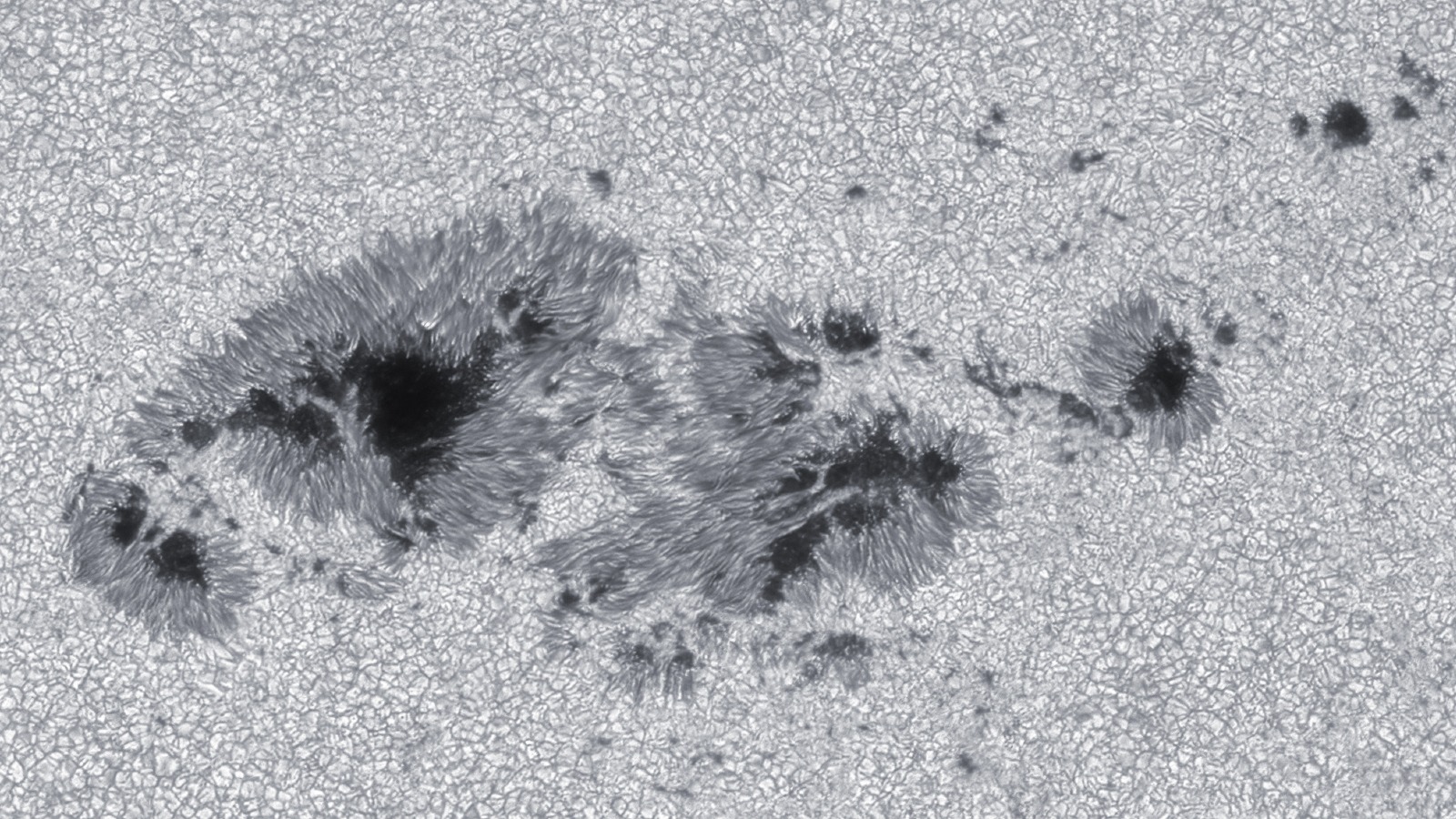

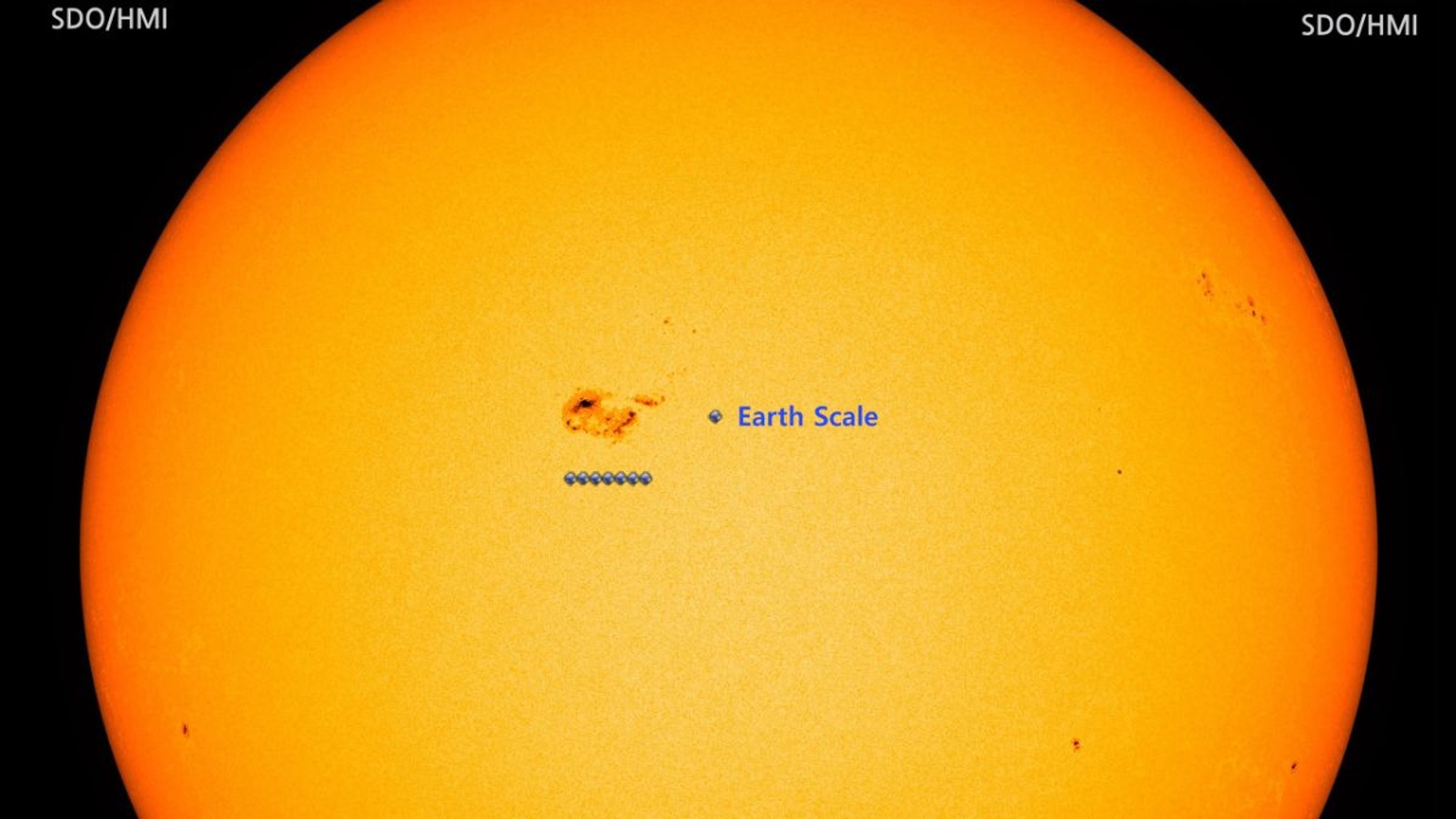

The enormous dark patch, named AR3354, emerged on the solar surface on June 27 and within 48 hours had grown to cover around 1.35 billion square miles (3.5 billion square kilometers), or 10 times wider than Earth. Space weather scientists were alarmed by the colossal sunspot's rapid emergence and feared it could spit out a barrage of potentially harmful solar storms, according to Spaceweather.com.

After growing to its full size, the sunspot produced a sizable M-class flare on June 29 but then remained calm until July 2, when it belched out an X-class flare aimed directly at our planet. (Solar flare classes include A, B, C, M and X, with each class being at least 10 times more powerful than the previous one.)

Radiation from the gargantuan X-class flare barreled into Earth's magnetic field and ionized the gases in the upper part of the atmosphere, turning the molecules into dense plasma. As a result, radio signals were scattered, causing radio blackouts in the western U.S. and parts of the eastern Pacific Ocean, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The disruption lasted for around 30 minutes, but things could have gotten much worse: Researchers initially suspected that the flare could have launched a coronal mass ejection (CME) — a cloud of fast-moving magnetized plasma. If a CME from a flare this size hit Earth, it would likely cause major disruption to Earth's magnetic field, known as a geomagnetic storm. This would have resulted in an even larger radio blackout affecting up to half of the planet, as well as potentially damaging satellites orbiting Earth and impacting power infrastructure on the planet's surface. But luckily, no CME was launched.

A3354 has not yet diminished in size and could still be capable of spitting out more M-class and X-class flares in the coming days, which could potentially launch CMEs toward Earth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A sign of solar maximum

Sunspots become larger and more frequent as the sun reaches its solar maximum — the most active part of its roughly 11-year solar cycle. During solar maximum, the number and intensity of solar flares also increase.

The current solar cycle officially began in December 2019, and scientists predicted it would peak in 2025 and be underwhelming compared with past solar cycles. However, Live Science recently reported that the next solar maximum will likely arrive earlier and have a stronger peak than initially expected. This latest solar flare is a further sign that the solar peak is fast approaching.

Related: 10 signs the sun is gearing up for its explosive peak — the solar maximum

A3354 is the largest sunspot region to emerge this year and the second-largest of this solar cycle, according to SpaceWeatherLive.com. The total number of sunspots is also ramping up faster than expected: For the last 28 months in a row, there have been more of the dark patches on the sun than experts predicted there would be, according to NOAA.

The X-class flare that hit Earth is the ninth of its kind launched this year —the same number as 2021 and 2022 combined. In January, a surprise X-class flare exploded from a hidden sunspot on the sun's far side and narrowly missed Earth, and in February, another X-class flare erupted alongside a plasma shockwave known as a "solar tsunami" and hit our planet, which also triggered radio blackouts.

Earth's upper atmosphere is also changing as it gets continually dosed with solar radiation: The thermosphere, Earth's second-last atmospheric layer, is currently warming faster than it has in the last 20 years after being bombarded by geomagnetic storms, and visual phenomena including auroras and aurora-like phenomena, such as airglow and STEVE, are also appearing more reguarly.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus