Gigantic 'hole' in the sun wider than 60 Earths is spewing superfast solar wind right at us

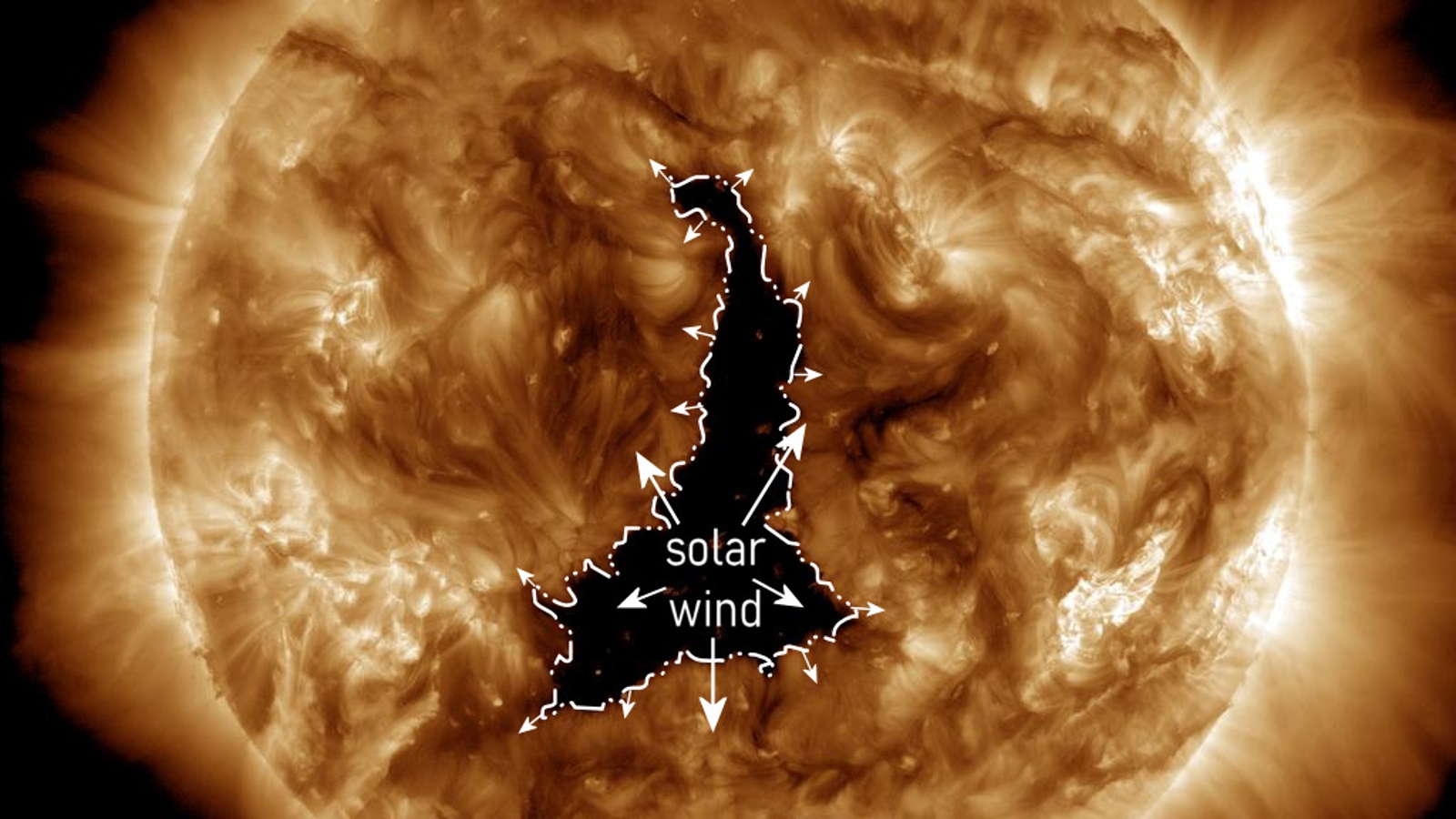

A monstrous dark patch, known as a coronal hole, recently appeared near the sun's equator. The temporary gap enables unusually fast solar wind to race toward Earth.

An enormous dark hole has opened up in the sun's surface and is spewing powerful streams of unusually fast radiation, known as solar wind, right at Earth. The size and orientation of the temporary gap, which is wider than 60 Earths, is unprecedented at this stage of the solar cycle, scientists say.

The giant dark patch, known as a coronal hole, took shape near the sun's equator on Dec. 2 and reached its maximum width of around 497,000 miles (800,000 kilometers) within 24 hours, Spaceweather.com reported. Since Dec. 4, the solar void has been pointing directly at Earth.

Coronal holes occur when the magnetic fields that hold the sun in place suddenly open up, causing the contents of the sun's upper surface to stream away in the form of solar wind, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Coronal holes appear as dark patches because they are cooler and less dense than the surrounding plasma. This is similar to why sunspots appear to be black — but unlike sunspots, coronal holes are not visible unless they are viewed in ultraviolet light.

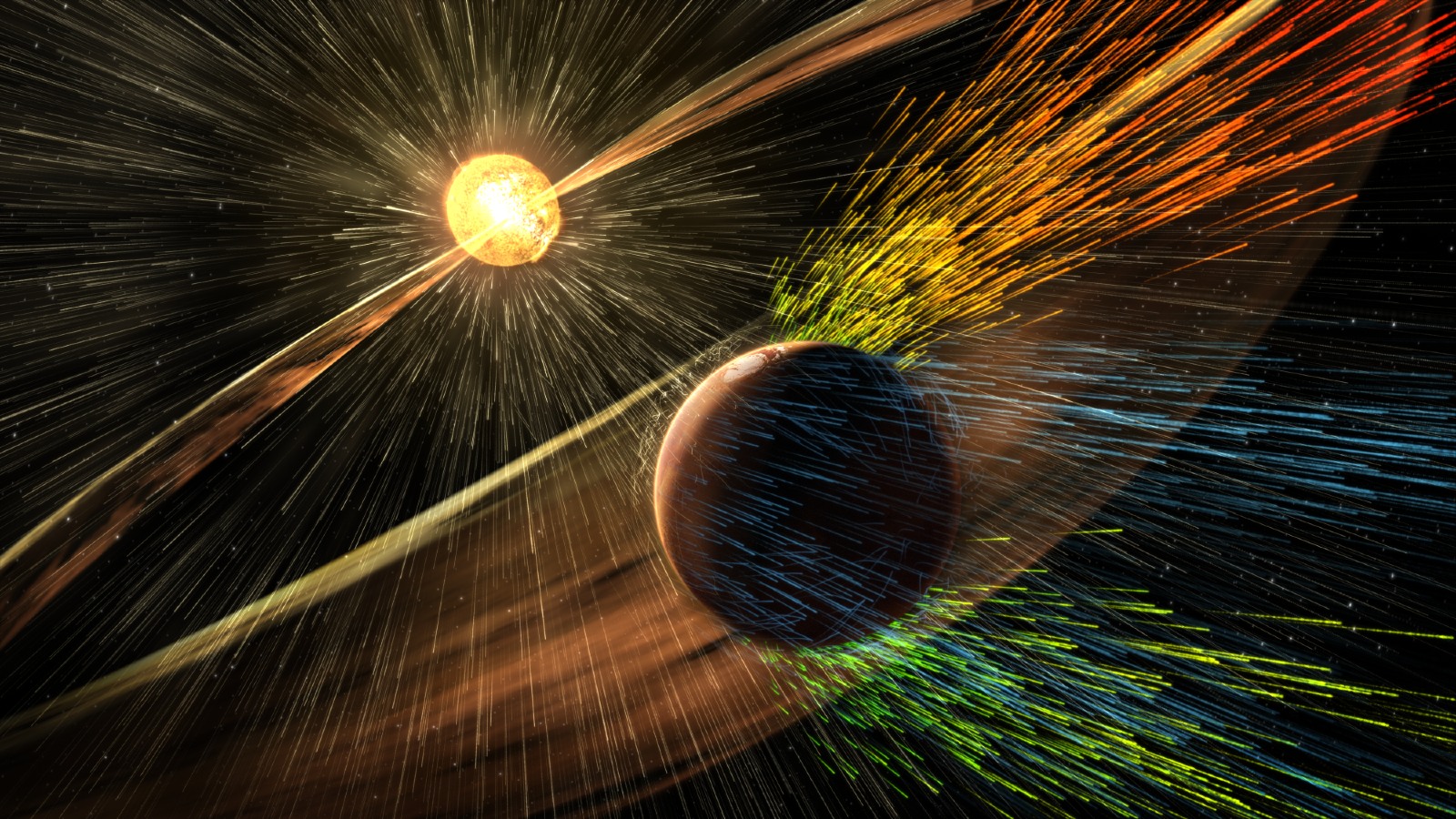

The radiation streams from coronal holes are much faster than normal solar wind and often trigger disturbances in Earth's magnetic shield, known as geomagnetic storms, according to NOAA. The last coronal hole to appear on the sun, which emerged in March, spat out the most powerful geomagnetic storm to hit Earth in more than six years.

Experts initially predicted this most recent hole could spark a moderate (G2) geomagnetic storm, which could trigger radio blackouts and strong auroral displays for the next few days. However, the solar wind has been less intense than expected, so the resulting storm has only been weak (G1) so far, according to Spaceweather.com. But auroras are still possible.

It is unclear how long the hole will remain in the sun, but previous coronal holes have lasted for more than a single solar rotation (27 days) in the past, according to NOAA. However, the hole will soon rotate away from Earth.

Related: 15 dazzling images of the sun

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Solar activity has been ramping up all year as the sun nears the explosive peak in its roughly 11-year solar cycle, known as the solar maximum. However, in a bizarre twist, the gigantic new coronal hole is not supposed to be part of this increase in solar activity.

Coronal holes can occur at any point throughout the solar cycle, but they are actually more common during solar minimum, according to NOAA. When they do emerge during solar maximum, they are normally located near the sun's poles and not near the equator. It is, therefore, a mystery how such a massive hole opened up near the equator when we are so close to the solar maximum.

However, over the last few weeks, there have been numerous other signs that the sun is getting more active.

On Nov. 18, a gigantic "sunspot archipelago" made up of at least five different sunspot groups emerged on the sun's near side and has since spat out dozens of solar storms into space. On Nov. 25, an explosive "canyon of fire" eruption near the sun's equator released a coronal mass ejection (CME) — a fast-moving cloud of magnetized plasma — that later slammed into Earth and triggered rare orange auroras. And on Nov. 28, an "almost X-class" solar flare shot out of the sun and birthed a cannibal CME that hit Earth and triggered a geomagnetic storm, which lit up lower latitudes with auroras over the weekend.

The recent surge in solar activity is likely a sign that we are right on the cusp of solar maximum. In October, scientists revised their solar cycle forecasts and now predict that the explosive peak could begin in early 2024.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus