Orbiting satellites could start crashing into one another in less than 3 days, theoretical new 'CRASH Clock' reveals

Researchers have proposed a theoretical timepiece, dubbed the "CRASH Clock," which tells us how quickly satellites would start colliding if they lost the ability to avoid each other, such as during a powerful solar storm. And its value is rapidly decreasing.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

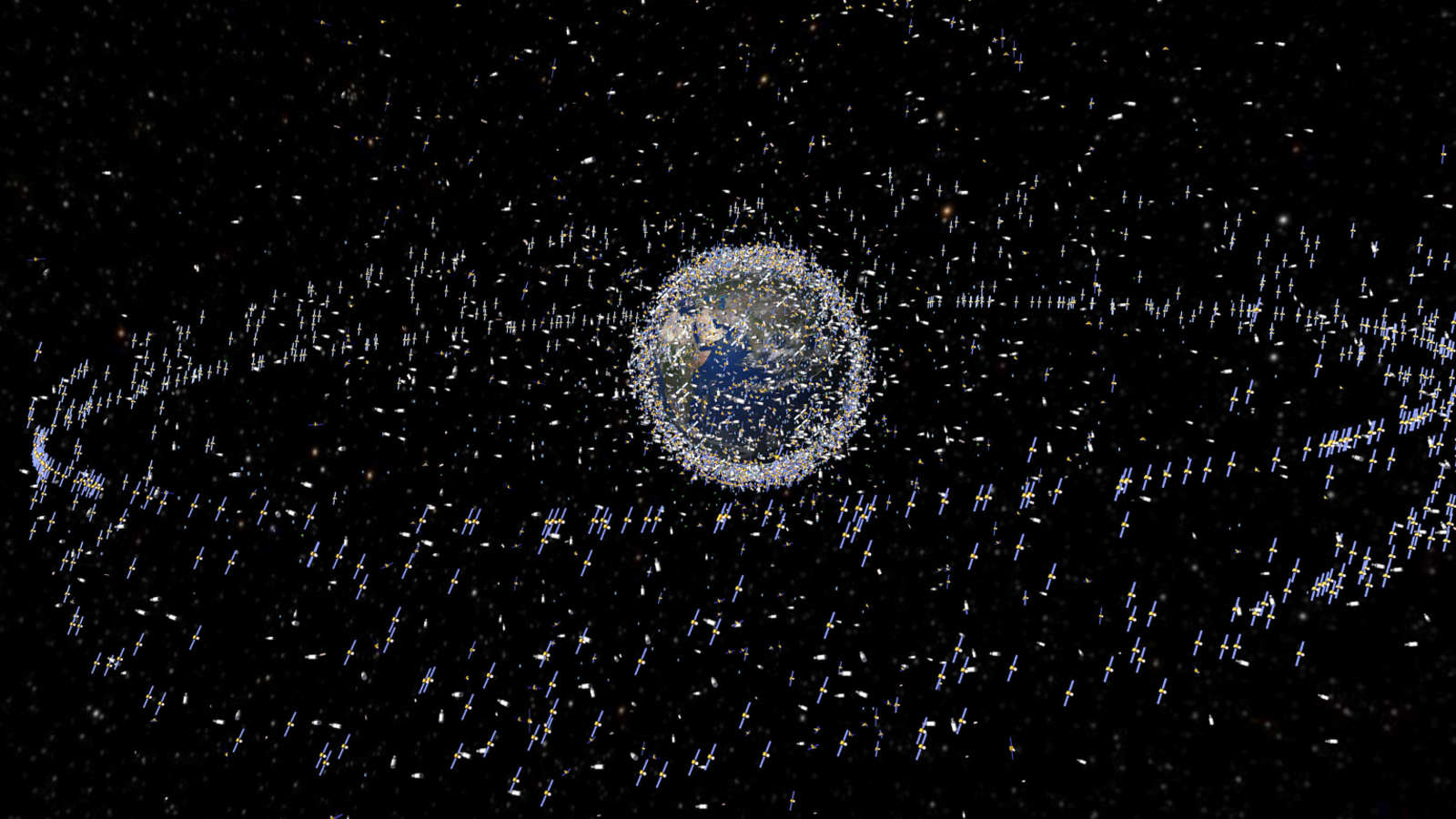

Earth-orbiting satellites could begin colliding with one another in less than three days in a worst-case-scenario scenario — potentially triggering a runaway cascade that may render low Earth orbit (LEO) unusable, a new preprint study warns. This is 125 days quicker than if an emergency had happened just seven years ago, according to the researchers' newly devised "CRASH Clock."

The number of spacecraft orbiting our planet is rising fast, thanks largely to the rise of satellite "megaconsetllations," such as SpaceX's Starlink network. As of May 2025, there were at least 11,700 active satellites around Earth, most of which are located in LEO — the region of the atmosphere up to 1,200 miles (2,000 km) above Earth. For context, that is a 485% increase on the roughly 2,000 satellites in LEO at the end of 2018, before the first Starlink launch in 2019. And all signs suggest that this is only the beginning.

One of the big problems with having so many satellites circling us is an increased chance they may collide with each another, creating clouds of fast-moving debris that could impact other spacecraft, including human-occupied space stations. Satellite operators are largely able to avoid these collisions. However, if they were to lose control of their respective spacecraft — either via a technical glitch, a cyber attack or a massive solar storm — they would be powerless to prevent a potential catastrophe.

Article continues belowIn a new study, uploaded to the preprint server arXiv on Dec. 10, researchers proposed a new way of measuring the risk of a collision occurring if every spacecraft was rendered inoperable by one of these worst-case scenarios. The team dubbed this metric the Collision Realization And Significant Harm (CRASH) Clock. By modelling the distribution of spacecraft in LEO, the CRASH Clock shows how long it would take for the first collision to occur. (This is similar to how the infamous "Doomsday Clock" shows us how far we are away from a hypothetical global armageddon.)

"The CRASH Clock is a statistical measure of the timescale expected for a close approach that could give rise to a collision," study co-author Aaron Boley, an astronomer at The University of British Columbia, told Live Science in an email. "The idea is that it can be used as an environmental indicator that helps to evaluate the overall health of the orbital region while enabling people to conceptualize just how much or how little room there is for error."

In the new paper, the team calculated that the value of the CRASH Clock by the end of 2025 was around 2.8 days, with a 30% chance that a collision could occur within 24 hours of an emergency that renders satellites inoperable. This is much less than the clock's predicted value for 2018, estimated to be 128 days, which would have given operators much more time to recover their assets.

These findings have not yet been peer-reviewed, and the study team now thinks that they slightly overestimated how short the CRASH Clock really is, Boley told Live Science. However, the rate at which these timeframes have changed, regardless of their exact values, is what is most concerning. (A new, more reliable value for the CRASH Clock is likely to be published later this year.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Seeing that difference [in values] is one factor that motivated us to develop the CRASH Clock further," Boley said. The fact that the value has decreased so significantly already is just as good an "indicator of the stress on orbit" as the CRASH Clock itself, he added.

The value of the CRASH Clock will likely continue to decrease further in the coming years as more satellites are deployed. In 2025, for example, there were 324 orbital launches, which is a new record and represents a 25% increase compared to 2024, SpaceNews recently reported.

The researchers have not predicted exactly how much the CRASH Clock will change in the coming years. However, they suspect that the current trend will continue: "Whether the CRASH Clock decreases will depend on the continued approach to industrializing Earth orbits," Boley said. "It could continue to get shorter if densification of orbital shells continues."

The most likely way that a CRASH Clock scenario would play out is via a sizable solar storm, which can temporarily scramble satellite systems with large doses of radiation, study lead author Sarah Thiele, an astrophysics researcher at Princeton University, recently told Live Science's sister site Space.com. During such an event, "it becomes impossible to estimate where objects are going to be in the future," she added.

If satellites remained offline for longer than the CRASH Clock value then multiple collisions could occur, which could push us dangerously close to the threshold of the Kessler Syndrome — a theoretical scenario where cascading collisions in LEO triggers causes space junk to exponentially increase to the point where nothing could safely operate there.

The researchers are reluctant to predict a timeframe for this scenario because there are too many variables surrounding subsequent satellite collisions, and nobody really knows at what point the Kessler syndrome will be triggered, Boley said. However, if we are not careful, we may soon "be in the early stages" of an irreversible cascade of collisions, he warned.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus