China has planted so many trees it's changed the entire country's water distribution

Huge "regreening" efforts in China over the past few decades have activated the country's water cycle and moved water in ways that scientists are just now starting to understand.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

China's efforts to slow land degradation and climate change by planting trees and restoring grasslands have shifted water around the country in huge, unforeseen ways, new research shows.

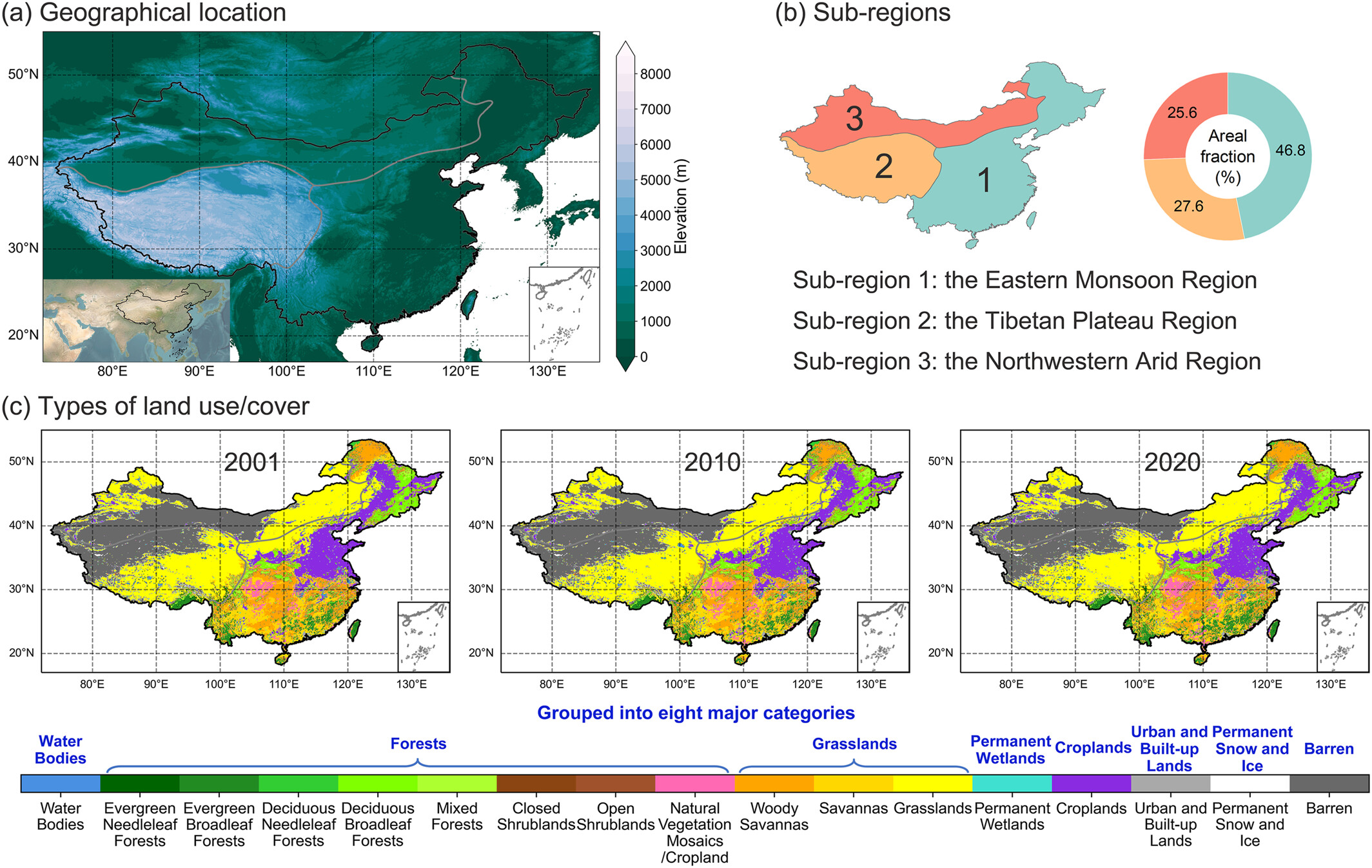

Between 2001 and 2020, changes in vegetation cover reduced the amount of fresh water available for humans and ecosystems in the eastern monsoon region and northwestern arid region, which together make up 74% of China's land area, according to a study published Oct. 4 in the journal Earth's Future. Over the same period, water availability increased in China's Tibetan Plateau region, which makes up the remaining land area, scientists found.

"We find that land cover changes redistribute water," study co-author Arie Staal, an assistant professor of ecosystem resilience at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, told Live Science in an email. "China has done massive-scale regreening over the past decades. They have actively restored thriving ecosystems, specifically in the Loess Plateau. This has also reactivated the water cycle."

Three main processes move water between Earth's continents and the atmosphere: evaporation and transpiration carry water up, while precipitation drops it back down. Evaporation removes water from surfaces and soils, and transpiration removes water that plants have absorbed from the soil. Together, these processes are called evapotranspiration, and this fluctuates with plant cover, water availability and the amount of solar energy that reaches the land, Staal said.

"Both grassland and forests generally tend to increase evapotranspiration," he said. "This is especially strong in forests, as trees can have deep roots that access water in dry moments."

China's biggest tree-planting effort is the Great Green Wall in the country's arid and semi-arid north. Started in 1978, the Great Green Wall was created to slow the expansion of deserts. Over the last five decades, it has helped grow forest cover from about 10% of China's area in 1949 to more than 25% today — an area equivalent to the size of Algeria. Last year, government representatives announced the country had finished encircling its biggest desert with vegetation, but that it will continue planting trees to keep desertification in check.

Other large regreening projects in China include the Grain for Green Program and the Natural Forest Protection Program, which both started in 1999. The Grain for Green Program incentivizes farmers to convert farmland into forest and grassland, while the Natural Forest Protection Program bans logging in primary forests and promotes afforestation.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Collectively, China's ecosystem restoration initiatives account for 25% of the global net increase in leaf area between 2000 and 2017.

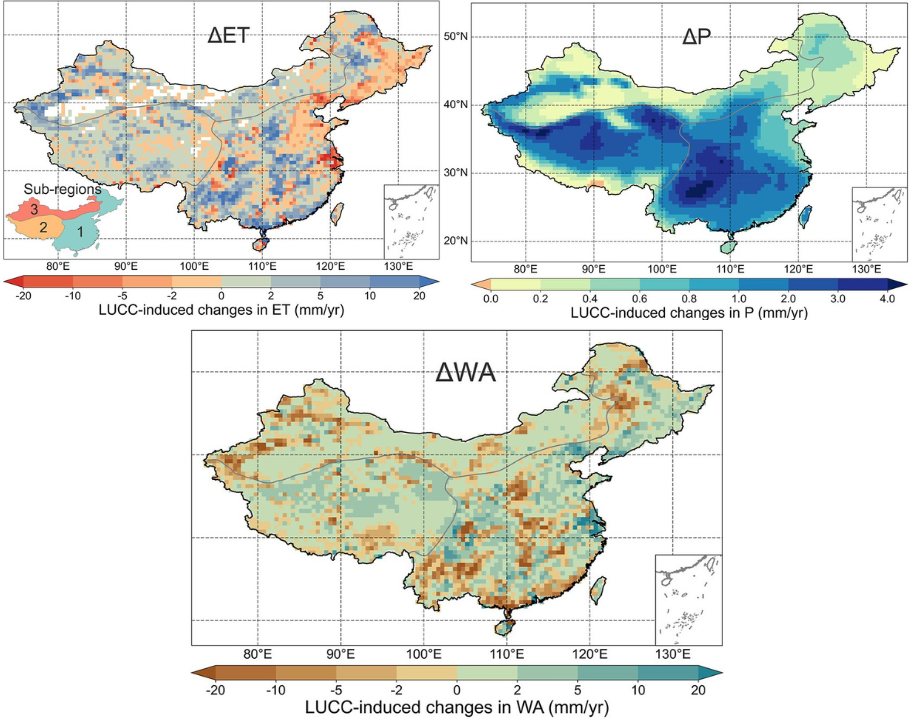

But regreening has dramatically changed China's water cycle, boosting both evapotranspiration and precipitation. To investigate these impacts, the researchers used high-resolution evapotranspiration, precipitation and land-use change data from various sources, as well as an atmospheric moisture tracking model.

The results showed that evapotranspiration increased more overall than precipitation did, meaning some water was lost to the atmosphere, Staal said. However, the trend wasn't consistent across China, because winds can transport water up to 4,350 miles (7,000 kilometers) away from its source — meaning evapotranspiration in one place often affects precipitation in another.

The researchers found that forest expansion in China's eastern monsoon region and grassland restoration in the rest of the country increased evapotranspiration, but precipitation only increased in the Tibetan Plateau region, so the other regions experienced a decline in water availability.

"Even though the water cycle is more active, at local scales more water is lost than before," Staal said.

This has important implications for water management, because China's water is already unevenly distributed. The north has about 20% of the country's water but is home to 46% of the population and 60% of the arable land, according to the study. The Chinese government is trying to address this; however, the measures will likely fail if water redistribution due to regreening isn't taken into account, Staal and his colleagues argued.

Ecosystem restoration and afforestation in other countries could be affecting water cycles there, too. "From a water resources point of view, we need to see case-by-case whether certain land cover changes are beneficial or not," Staal said. "It depends among other things on how much and where the water that goes into the atmosphere comes down again as precipitation."

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus