Why do European cities have milder winters than those in North America, despite being at the same latitude?

London is at the same latitude as Calgary, Alberta. So why is the Canadian city about 15 degrees Fahrenheit (8.3 degrees Celsius) cooler in January?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Broadly speaking, the farther you get from the equator, the colder the average temperatures are. It's a major reason why the North and South poles are some of the coldest places on Earth, while many of the hottest deserts are concentrated near the center of the planet.

But that logic doesn't apply to parts of Western Europe. For example, the average January high in London is 47 degrees Fahrenheit (8.3 degrees Celsius), but Calgary, Alberta, 4,400 miles (7,100 kilometers) west of London, has an average January high in the low 30s (less than 1 C). Both cities are at nearly the same latitude: London sits at 51.5 degrees, and Calgary is at a latitude of 51 degrees, meaning they are about an equal distance from the equator.

Those cities aren't alone. New York City and Madrid lie at roughly the same latitude, but Madrid's average high in January is about 50 F (10 C), compared with 40 F (4.4 C) in New York City. If you were to find yourself in Vienna, Austria, in mid-January, the average high would be about 37 F (2.8 C), but hop about 4,500 miles (7,200 km) west, and besides the difference in language and food, you would find yourself in Grand Forks, North Dakota, where the average January temperature sits at 17 F (minus 8.3 C).

Sign up for our weekly Life's Little Mysteries newsletter to get the latest mysteries before they appear online.

Overall, the average January temperature for the contiguous United States in 2024 was about 32 F (0 C), but the average temperatures in a number of countries throughout Western Europe felt warmer: Germany averaged 35 F (1.5 C), the United Kingdom averaged almost 39 F (3.8 C) and Spain averaged 47 F (8.4 C) in January 2024.

So why do some Western European cities have milder winters than those in parts of North America if they share the same latitude?

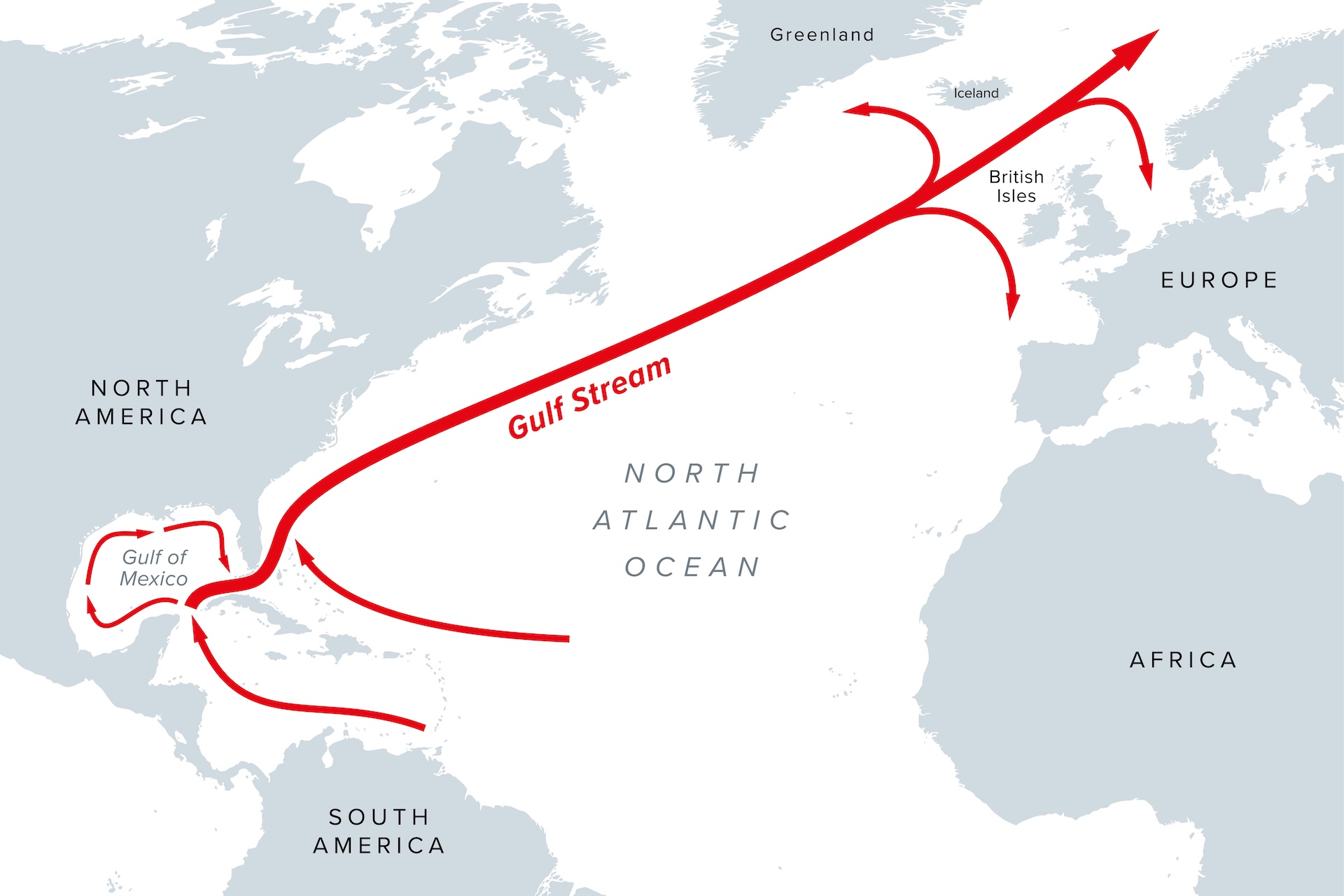

A key reason is a system of ocean currents in the Atlantic brings heat from the tropics up toward Europe, said Ben Moat, head of open ocean physics at the National Oceanography Centre in the U.K.

"If you imagine a wood stove in your house, it draws cold air towards the heat. It rises and circulates," he told Live Science. "That's also what happens in most of the world's oceans."

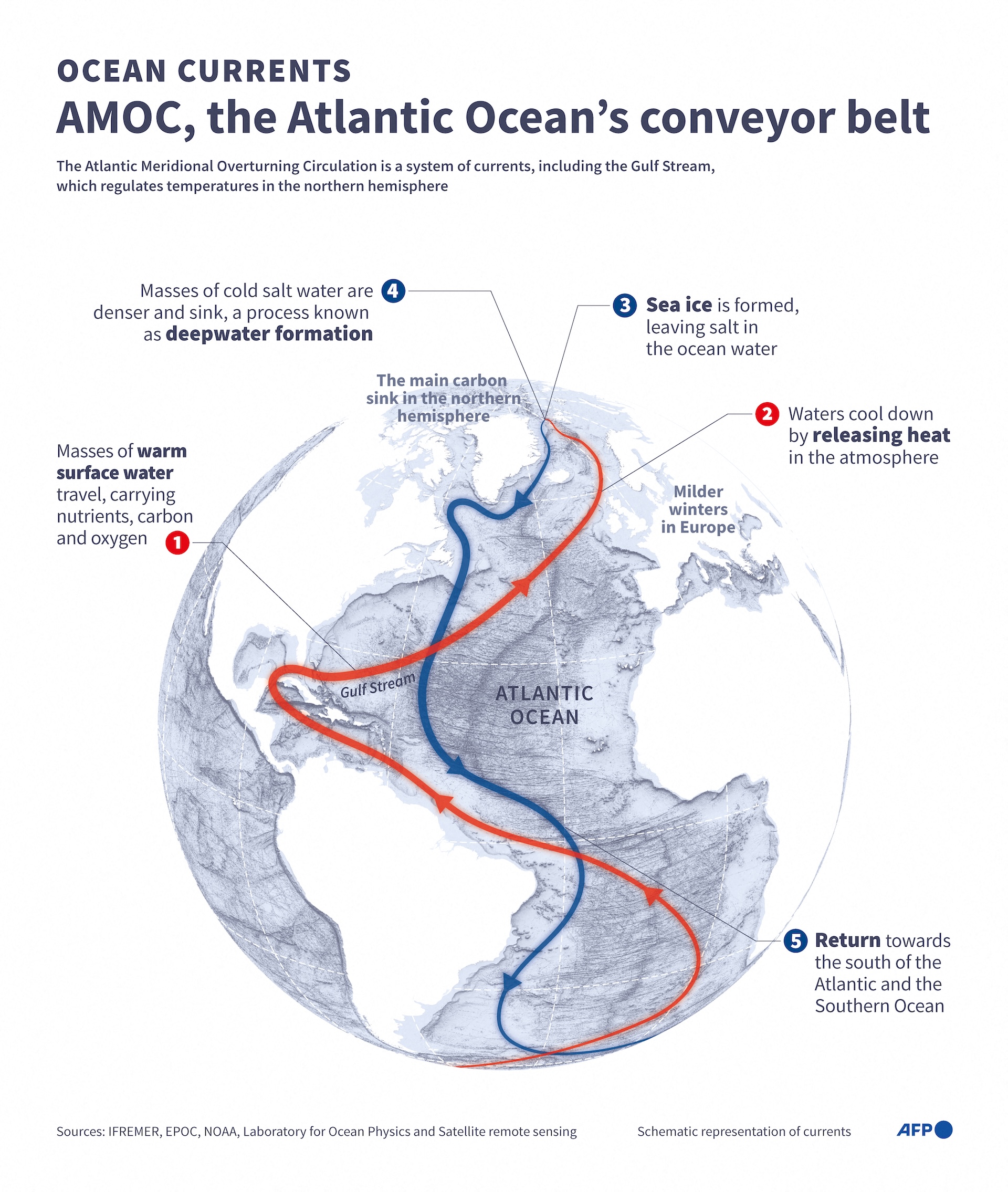

That system is called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), a web of ocean currents that loop through the Atlantic Ocean. The AMOC works like a massive conveyor belt that moves 600 million cubic feet (17 million cubic meters) of water per second and 1.2 petawatts of heat, roughly the amount of heat put out by a million power plants running simultaneously, Moat estimates.

The massive amount of warm water rushing to the Northern Hemisphere also heats up the atmosphere. Prevailing winds known as the westerlies then blow from west to east and carry the warm ocean air in the atmosphere inland like a "fan-assisted heater," David Thornalley, a professor of ocean and climate science at University College London, told Live Science in an email. The westerlies are especially strong in the winter, which helps create the "nice warm winter climate of southwest England," he said, at least compared to the winter climate of places at similar latitudes in North America, like Calgary or Winnipeg.

The oceans, Gulf Stream and jet stream

The European continent is also warmer because it is relatively narrow and surrounded by water. Simply being next to an ocean makes a big difference, Thornalley said, "because water can store so much heat. It builds up and stores heat in the summer, which it then releases to the atmosphere in winter. … It is why places next to the ocean tend to have milder winters than in the middle of a continent."

That also helps explain why parts of Europe tend to have cooler summers — while the ocean is warmer than the air in the winter, in the summer the ocean is cooler, he said. Over the summer, the cooler water reduces the temperature of the surrounding atmosphere which the westerlies then blow inland.

Unfortunately for cities like New York and Boston in the Northeast U.S., being next to an ocean doesn't necessarily mean warmer winters. A major reason is because of the Gulf Stream, a part of the AMOC that brings warm water up the East Coast of the U.S. It forms atmospheric waves that draw cold air from the northern polar region and delivers frigid air to the Northeast — potentially accounting for 30% to 50% of the temperature difference across oceans — according to a 2011 study in the journal Nature.

Another band of wind has a big impact on North America's climate: the jet stream. Similar to the westerlies, the jet stream flows west to east, but the jet stream operates in the upper levels of the atmosphere, and when it flows downstream of the Rocky Mountains, it "has a tendency" to dip south and allow "cold air from polar latitudes" to spill over North America, Sybren Drijfhout, a professor of physical oceanography and climate physics at the University of Southampton in the U.K., told Live Science in an email.

The jet stream is generally stronger in the winter because the temperature difference across the stream is larger during winter months: "bringing Canadian air to the U.S." can therefore lead to larger drops in temperature and more extreme weather as a result.

But the temperate climate in much of Europe may not last forever, especially as extreme weather is only becoming more common with climate change. Peter Ditlevsen, physicist and professor at the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen, co-authored a 2023 paper warning that the AMOC — which is critical to regulating the global climate, not just Europe's — could collapse due to human-caused climate change between now and 2095, which is much earlier than previous predictions.

The climate in certain parts of Europe would look more like Alaska or northern Canada, Ditlevsen told Live Science. "There have been some studies saying that agriculture in Ireland and England would fall by, you know, 50%," he said. "Obviously, we hope that this is not going to happen."

Equator quiz: Can you name the 13 countries that sit on Earth's central line?

Jesse Steinmetz is a freelance reporter and public radio producer based in Massachusetts. His stories have covered everything from seaweed farmers to a minimalist smartphone company to the big business of online scammers and much more. His work has appeared in Inc. Magazine, Duolingo, CommonWealth Beacon, and the NPR affiliates GBH, WFAE and Connecticut Public, among other outlets. He holds a bachelors of arts degree in English at Hampshire College and another in music at Eastern Connecticut State University. When he isn't reporting, you can probably find him biking around Boston.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus