In 'Secrets of the Brain,' Jim Al-Khalili explores 600 million years of brain evolution to understand what makes us human

In his new BBC show, Jim Al-Khalili journeys through hundreds of millions of years of brain evolution. Live Science spoke to him about what he learned along the way and how this knowledge sheds new light on human cognition.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The first hint of a brain developed on Earth around 600 million years ago, and now, some version of the organ can be found in nearly every animal in the world.

Humans have the largest brain size relative to body size of any species, as well as an impressive ability to accumulate knowledge over time. And yet, the human brain is remarkably similar to the brains of other animals; they have the same electrical and chemical signaling system.

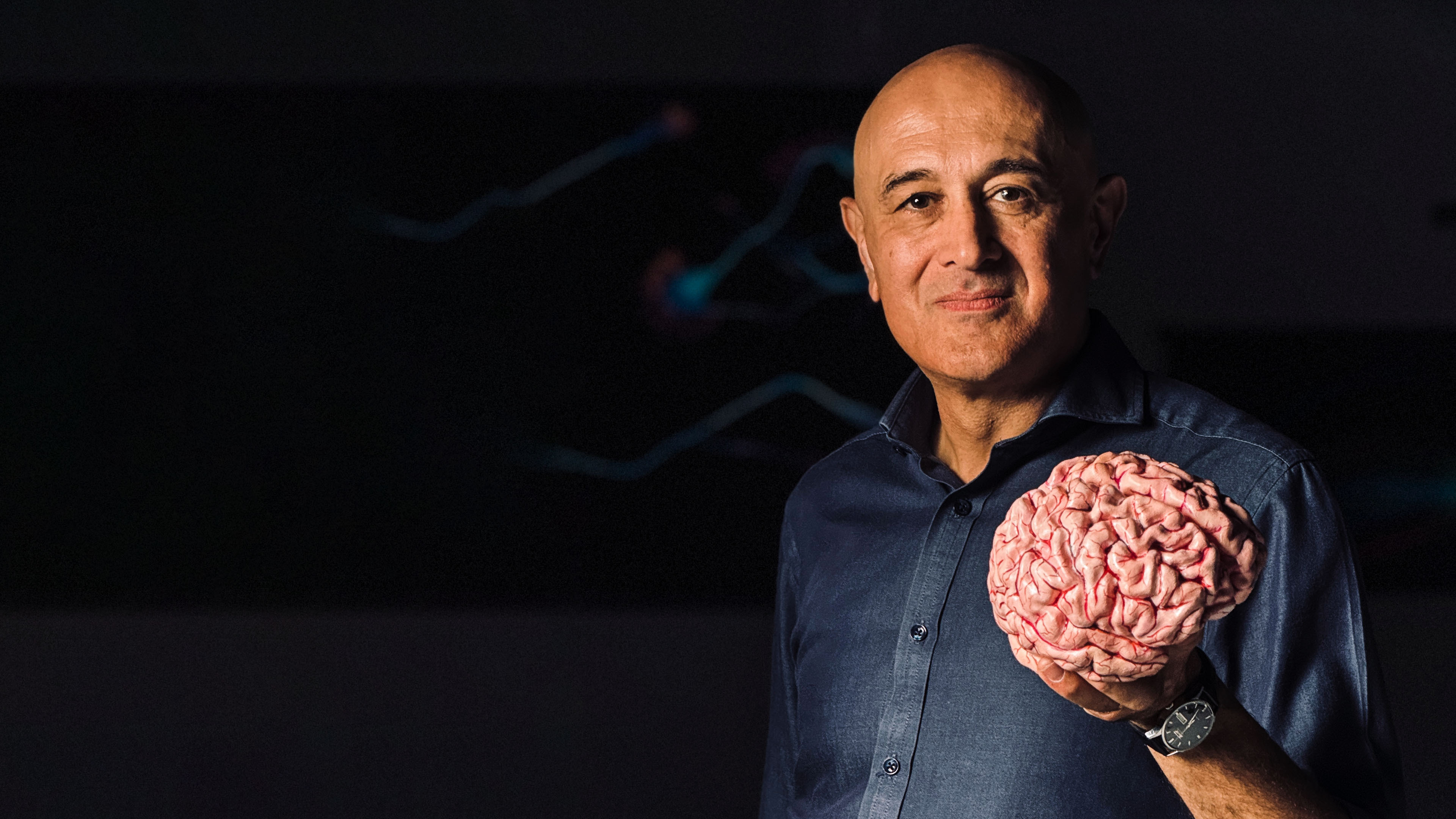

The vast evolutionary history of the brain, from the very first nerve cells to the modern human cerebrum, is covered in a sweeping two-part BBC series presented by Jim Al-Khalili, a renowned science communicator and theoretical physicist at the University of Surrey in the U.K.

In "Horizon: Secrets of the Brain," Al-Khalili surveys the animals and fossils shaping our understanding of how the brain evolved over millions of years, and the scientists unraveling each piece of the puzzle. Live Science picked Al-Khalili's brain about the show, how the human brain evolved and what the past 600 million years of evolution means for us today.

"Secrets of the Brain" will be available in the U.K. from Sept. 29 on BBC Two. For British residents abroad with with a valid TV license will need to use a VPN — or Virtual Private Network — to tune into iPlayer as usual. Our colleagues at TechRadar recommend NordVPN.

Sophie Berdugo: We normally think of you as being in the realm of theoretical physics — what led you to this show about the brain?

Jim Al-Khalili: In part because I do "The Life Scientific" on BBC Radio 4, I'm quite comfortable saying, "This is an area I don't work in; it's not my specialist area, but I want to talk to someone who does know what they're talking about." So I thought this was a good opportunity to learn about something.

After all, the human brain is the most complex system in the entire universe, and so we don't understand how it works entirely. We're starting to learn about human consciousness and so on, but one of the things that's missing is that I didn't understand how it fitted into evolutionary history.

We know humans are smart and smarter than any other animal, and usually it's [the explanation is] "Oh, that's because we developed language, or because we've got opposable thumbs." But I knew it had to be more than that. And what I found fascinating was digging into this long story of how the brain — not necessarily the human brain — but how the brain evolved and grew over hundreds of millions of years, rather than just 1 or 2 millions of years.

SB: Were there any questions that you had going into the docuseries that you ultimately discovered science doesn't actually know the answer to yet?

JAK: Well, certainly the ideas of what separates humans from our primate cousins. The usual argument is that we developed language or that we have metacognition and theory of mind. [Metacognition refers to an awareness and understanding of one's own thought processes, and theory of mind refers to an ability to understand that other individuals have their own perspectives and mental states.]

But, of course, other primates do have that as well, to a lesser extent. This idea of metacognition, [and] being able to imagine yourself in another person's shoes, other primates have that as well.

Then there's the development of language. But one of the surprising things I learnt on the program was that, while other primates like gorillas don't have language, they develop syntax. The idea that syntax doesn't necessarily relate to language and words and grammar, but more broadly, it means putting things in some logical order. How gorillas reach for and grab some nettles and how they fold them up and roll them in a ball and eat them and so on, that also is a form of syntax. So the idea that syntax evolved before language and that that was the important step left me thinking, "So what is it that separates us?"

Then the final part of the program says it's because we are social animals; the "social brain hypothesis" explains that we have such large brains because we have complex social systems and interactions with each other. But then other primates have that as well — bonobos and chimpanzees and so on.

Whatever separates humans from other higher mammals... it's not because we created a complex world. It's something else.

So I was left with this question that all the things that we thought should separate us from other primates — language, metacognition, social brains — all exist in the other primates. We have accelerated away from them in a way that is, you know, it's not just a little bit — we are way, way more complex in terms of our thinking and thoughts than other primates. So that's something that I still feel, personally, I haven't got a clear answer to.

SB: I was also left thinking that at the end of the second episode — that we have so many similarities with our closest living relatives and also species that are distantly related to us, like marine mammals. But how is it that the evolution of our brain ultimately resulted in us being able to have this conversation now and think about how other animals think?

JAK: My view is that there's some sort of bootstrap mechanism going on so that the more complex the world around us is, and the complexity of our actions and interactions become; the more there's a need for the brain to process the data, to analyze, to calculate and so on. So there's nothing specifically different about the human brain from other higher mammals', in terms of intelligence. It's just a matter of degree.

We live in complex societies now, but I wouldn't say that we are more intelligent than a human five, six, seven thousand years ago. Evolution doesn't work that fast. And they didn't have books and electronics and so on, and they were just as intelligent as us.

So whatever separates humans from other higher mammals, whether it's primates or dolphins or whatever, it's not because we created a complex world. It's something else. I'm sure it's not something banally simple like opposable thumbs. Yeah, I'm sure that helps, but that can't be the answer.

SB: And in the show, you explore hand adaptations and changes in social environments as separate events, when they're ultimately all evolutionarily linked.

JAK: Oh absolutely, yeah, and I think that's one of the shortcomings of having to tell a story like this. You have to break it down into steps.

It's all very well talking about early organisms in the sea before the Cambrian explosion and the eye developing before the brain. Great, that's quite neat. So there are certain sequential stories that one can tell, and then with the various extinction events that accelerated evolution, just for survival purposes.

But you're right; certainly once you get to the last, say, 10 million years and primates are evolving, lots of different factors are competing with each other and bootstrapping and interconnected. But to tell the story, you have to break it down into steps, and sometimes that makes it sound like, "Well, first we had to develop this and then once we got that sorted, then we developed something else," and so on.

SB: Was there a period within the 600 million years covered in the program that you would love to spend a day in, to see exactly how the organisms alive at the time were behaving and surviving, and how that relates to brain evolution?

JAK: What I found very fascinating was the Permian mass extinction, sometimes called the "Great Dying," where almost all life disappeared. Volcanic eruptions, climate change, ocean acidification and all that stuff. But that 5% [of marine animals] did survive. [90% of life on Earth was killed.]

I did a piece to camera in the program where I said, "They could slither under the mud, find nooks and crannies." But it would be fascinating to see, what sort of environment was that 250 million years ago that wiped out 95% of all life, but 5% survived? Did they just get lucky? Did they just keep their heads down? Or did they have something different about them that the other 95% didn't have that they managed to survive?

They weren't just smarter, you know. They had to become smarter in order to survive, because the brain needed to evolve to cope with the new challenges. But I hadn't quite appreciated that the Permian mass extinction almost stopped life from continuing on Earth. So that's fascinating. Thankfully, some did survive.

SB: I think we can all be thankful that there were some who survived!

We worry about climate change now, but the climate change that happened after the Permian mass extinction was so much more extreme. How could any life possibly still carry on existing? I just find that fascinating.

SB: Absolutely, and that was something I wanted to ask you: How does learning about the evolution of the brain help us understand ourselves and the world today, especially in light of challenges like the climate crisis and the advent of artificial intelligence (AI), which you touched in the show?

JAK: Being able to appreciate the uniqueness of the human brain, or something about our brain that makes us uniquely human, I think is an important lesson.

Our relationships with each other, that we have these complex structures and societies — we have shared cultures and beliefs and memories and history and so on, which is something that is uniquely human. Something that if we develop AI … and I expect this will happen, it will one day be conscious. It will be sentient, self-aware, but it won't be human. Because it hasn't been along that journey that we've been through. You can't simulate or replicate that.

Nor would we feel we should. Why would you want to create artificial intelligence that's exactly like a human? Well, you've got humans to do whatever you want the AI to do. And if it becomes conscious and self-aware, then it should have just as many rights as a human; it's living and sentient, then it's not just a machine.

However clever you think ChatGPT is, it's not conscious, but your dog is conscious

For people to appreciate just how special the brain is and how special humans are, [it] might give people pause for thoughts, given that we don't seem to have learned lessons about utilizing those aspects of what we say makes us human. We sometimes forget empathy, compassion and kindness. Those sorts of things make us human.

And you'd think with the current issues and challenges we face in the 21st century, it's a reminder of how long a journey, not humans, but our brain, the central mechanism, has had in reaching where it's at now. To somehow waste that would be quite tragic.

SB: I was really struck by the similarities the show highlighted between humans and other life on Earth — for instance, at the very start of the first episode, you talk about the zooplankton and how they have the same rod and cone cells in their eyes that we have today.

JAK: The axon and the neuron are things that evolved to serve a particular task. Light-sensitive receptors needed to send signals to motion cells to tell an early organism to move towards or away from the light. But those axons and neurons are what we have in our brains now, so clearly they evolved to create a certain job and clearly then became useful. And once they became more interconnected, their complexity served more and more different purposes.

So there is that, that the brain has in common. And of course we are using neural networks [computer systems inspired by the network structures of the brain] to develop artificial intelligence. So that trick is so useful that that's become the standard way of developing machine learning in AI, even though the AIs that we have today are still dumb. They may fool us into thinking that they're being smart and we're having a conversation with them, but I always say, "However clever you think ChatGPT is, it's not conscious, but your dog is conscious."

ChatGPT, if in the middle of a conversation, you then leave your laptop and go off on holiday for a week, ChatGPT isn't sitting there thinking, "Oh, I wonder where Jim's gone. I was having a great chat. I miss him." But your dog would miss you. So your dog may not be able to talk to you and appear as though it's as clever as you, but it has that special thing called consciousness which AI doesn't yet have.

Editor's note: This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sophie is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She covers a wide range of topics, having previously reported on research spanning from bonobo communication to the first water in the universe. Her work has also appeared in outlets including New Scientist, The Observer and BBC Wildlife, and she was shortlisted for the Association of British Science Writers' 2025 "Newcomer of the Year" award for her freelance work at New Scientist. Before becoming a science journalist, she completed a doctorate in evolutionary anthropology from the University of Oxford, where she spent four years looking at why some chimps are better at using tools than others.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus