'People made it out of the cities alive': Tracing the survivors of Pompeii and Herculaneum, 2,000 years after Vesuvius erupted

Several lines of evidence, from chiseled inscriptions to missing horses, suggest that thousands of people survived the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in A.D. 79.

Around 2,000 years ago, the eruption of Mount Vesuvius obliterated Pompeii and Herculaneum, entombing the two cities and victims within a scorching mix of molten rock, pumice, ash and gas. With the Roman cities frozen in time, archaeologists know a huge deal about the lives of those who perished — but what about the survivors?

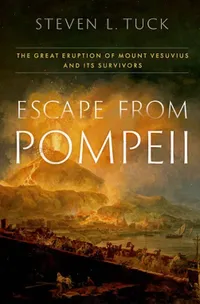

In this excerpt from "Escape from Pompeii: The Great Eruption of Mount Vesuvius and Its Survivors" (Oxford University Press, 2025), author Steven L. Tuck, history professor at Miami University in Ohio, examines the historical and archaeological evidence of the people who escaped the destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum, tracing them on their journey to start a new life outside the shadow of the volcano.

Related: Read our interview with Steven Tuck for more insights into the survivors.

This book starts from a straightforward question: did anyone survive the A.D. 79 eruption of Vesuvius? That of course leads to a host of related questions: if anyone did survive, who were they, where did they resettle, under what conditions, and how did they rebuild their lives in the post-eruption period? Finally, what does this tell us about the Roman world and the functioning of its government, social networks, and economy?

Unfortunately, no eyewitness accounts of the eruption survive from Pompeii or Herculaneum. The closest we have are the two letters from Pliny the Younger to the historian Tacitus that narrate his experiences and those of his uncle during the eruption. Significantly, Pliny does record the emotional reactions and activities in response to the eruption of those at Misenum: the people in that community, which was about 28 miles (45 kilometers) due west of the volcano by road, were clearly distressed but did not abandon their families in the crisis.

This was behavior they apparently had in common with those at Pompeii and Herculaneum. "You could hear the shrieks of women, the wailing of infants, and the shouting of men; some were calling their parents, others their children or their wives, trying to recognize them by their voices."

There exists a popular perception that everyone in Pompeii and Herculaneum perished in the eruption. This is understandable given the presentation of the disaster in popular culture [...] by contrast, a reader of academic work on Pompeii and Herculaneum might reasonably believe that the question of survivors from the eruption of Vesuvius is already settled [...] In fact, scholarly consensus has developed that contrary to popular perception, much — perhaps even a majority — of the populations of Herculaneum and Pompeii probably survived the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

'Evidence from absence'

At both Pompeii and Herculaneum we can find a great deal of indirect evidence of population survival, at least during the early stages of the eruptive event. Much of this has not been recognized for what it is because it is evidence from absence. Specifically, many of the customary household objects are not where we would expect them to be and forms of transportation such as boats, horses, and wagons are missing or, as far as we can tell, misplaced.

It is hardly surprising that this evidence has not been studied in depth before now, given the hundreds of thousands of objects, both intact and broken, found absolutely everywhere — indoors and outdoors, and in all types of buildings — at the two sites. On the whole, however, the absence of certain objects seems to indicate at least initial survival and plans to flee from the cities.

The patterns of destruction, human remains, and missing objects and transport animals at Herculaneum and Pompeii provide evidence that many residents of the two cities escaped. Other evidence for this proposition comes [from] the eruption sequence itself and from the date of the eruption and the location of the regional market outside of the two cities on that date. Taken singly, none of these pieces of evidence prove escape. Taken together, however, they create a pattern that supports the conclusion that people made it out of the cities alive. [...] The search for survivors also involves discovering a pattern of evidence for these survivors' resettlement.

This research for this book began with the hypothesis that some escapees could be identified, but these would be only a few extremely rich men who saw the eruption, turned their house keys over to an enslaved caretaker, and left town immediately in the direction away from the eruption. This does not seem to have been the case. It turns out that those who escaped were really a cross section of the population in their cities of origin.

Where did the survivors go?

We can say with certainty that a variety of people from both Pompeii and Herculaneum escaped the eruption of Vesuvius, although more escaped from the larger city of Pompeii. These people included rich and poor, men, women, and children. We can say that at least 172 named individuals, probably representing about 3,000 household members, can be traced.

How they managed to escape is harder to determine, but some seem to have lived on the edges of the affected cities, where escape was easier. Others may have been away from the cities on the day of the eruption, possibly at the market at Puteoli. The majority did not go far: they resettled in coastal Campania, primarily along the coast from Naples northward to Puteoli, Misenum, and Cumae. Smaller numbers are found further afield at Capua, Nola, Nuceria, and Aquinum, and a larger group resettled at Ostia.

The evidence suggests that they escaped and resettled as families in communities that they probably selected themselves based on social or economic networks. They were not resettled by the government, but the government did, however, respond to the eruption with relief efforts intended to help these communities. Roman government did matter, but in terms of response and relief, not rescue, despite the initial response of Pliny the Elder and the Roman fleet at Misenum.

Individuals can perhaps be traced further to — in modern terms — central Italy, Spain, and Romania. Modern studies of refugees and their movements, effects on their new communities, and the circumstances of their new lives can help to inform our understanding of the lives of these people, who survived a horrific natural disaster and, in some cases, rebuilt their lives, integrated into their communities, but did not wholly abandon their personal identities and culture as they carried on.

Excerpt from Escape from Pompeii: The Great Eruption of Mount Vesuvius and Its Survivors by Steven L. Tuck. Copyright © 2025 by Steven L. Tuck, and published by Oxford University Press on October 20, 2025. All rights reserved.

Escape from Pompeii: The Great Eruption of Mount Vesuvius and Its Survivors — $29.99 on Amazon

By asking new questions about Pompeii and innovatively examining the evidence, Escape from Pompeii proves the survival of Pompeians and Herculaneans after the eruption. It sheds new insight into their lives, pre- and post-eruption, and provides new conclusions about the Roman world and its response to unimaginable suffering.

Steven L. Tuck is a professor of classics at Miami University in Ohio. He has conducted archaeological fieldwork and research in Italy as well as in Greece, England, and Egypt. He teaches courses on the art, history and archaeology of the classical world and has published a textbook on Roman art history and numerous academic journal articles.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus