Trio of 'black mesas' leftover from Paleozoic era spawn rare sand dunes in the Sahara — Earth from space

A 2023 astronaut photo shows three dark hills, or mesas, towering above part of the Sahara desert in southern Mauritania. The structures are remnants of a single Paleozoic era formation, and have helped to create a series of striking sand dunes.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Where is it? Guérou, Mauritania [16.930575400, -11.759622605]

What's in the photo? Three black mesas surrounded by unusual sand dunes in the Sahara Desert

Who took the photo? An unnamed astronaut onboard the International Space Station (ISS)

When was it taken? May 3, 2023

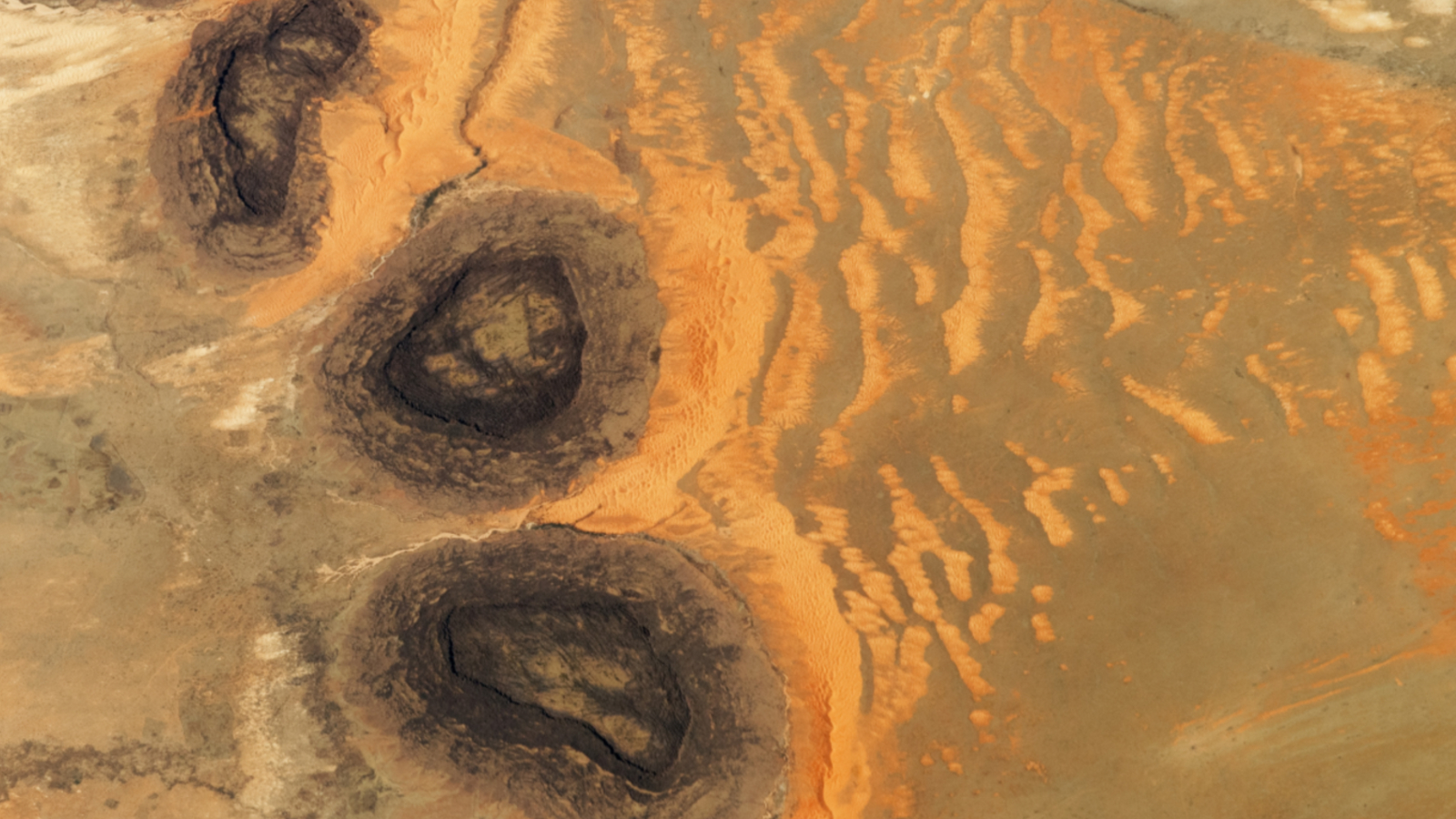

This intriguing astronaut photo shows a trio of ancient "black mesas", which sit side-by-side in the Sahara desert. The dark structures have enabled a series of rare sand dunes to form around them while also creating a surprising "dune-free zone."

The three mesas, or flat-topped hills, are located around 8 miles (13 kilometers) northwest of the town of Guérou in southern Mauritania, which is home to around 22,000 people. The mesas are made from sandstone and rise steeply above the surrounding plains, reaching between 1,000 and 1,300 feet (300 and 400 meters) above the ground. The largest of the trio is approximately 6 miles (9.5 km) across at its widest point, while a fourth mesa is located just north of the trio, but is positioned just out of frame.

The dark color of these circular hills is the result of "rock varnish" — a black, clay-based coating, rich in manganese and iron oxides, that forms on exposed and arid rocks over thousands of years, according to NASA's Earth Observatory. This coating was likely partly fixed in place by microorganisms and is made up of multiple micrometer-thick laminations, according to Science Direct.

To the west of the mesas (on the left of the photo) is a barren rocky plain with a surprising lack of sand dunes. But to the east of the flattened hills, you can see several sizable dunes that are seemingly flowing away from the black rocks like a rippling tail.

There are two main types of sand dunes visible in the image. The first type are rare "climbing dunes," which are the larger, ridge-like piles of sand that have piled up along the mesas' eastern walls. The second type are "barchan dunes," which are more common and make up the mesas' stripy tail. In both cases, the dunes have a distinctive reddish-yellow hue.

The sand dunes only form on the eastern side of the mesas because the wind predominantly blows from that direction, carrying sand that then gets caught on the sloped elevations surrounding the black rocks.

Sand does not accumulate to the west of the mesas because of a phenomenon known as "wind scour," which results from superfast vortices within the wind that gets squeezed in between the mesas, which blow sand away from the flattened hills, according to the Earth Observatory.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

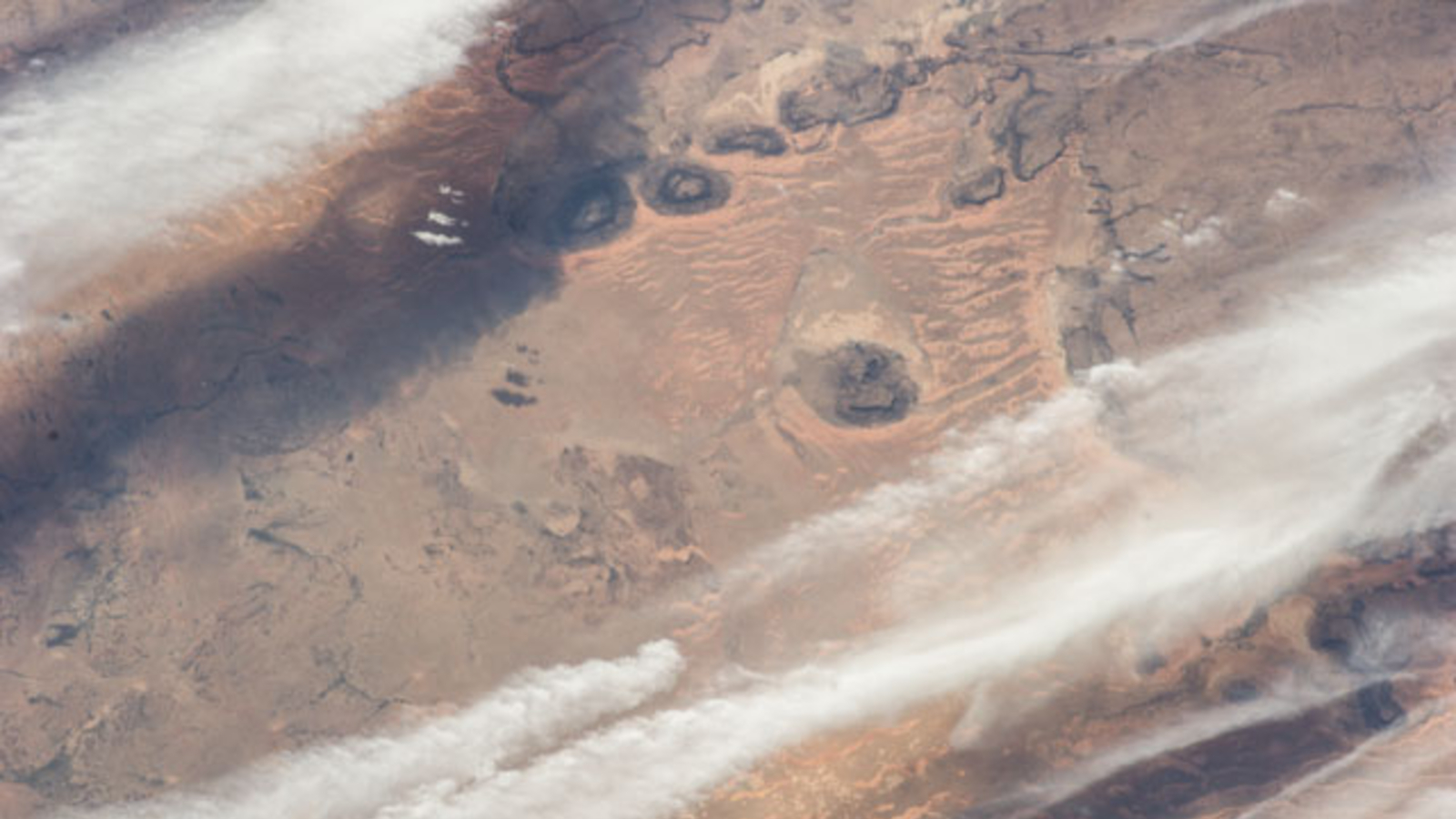

Another astronaut photo, taken in 2014, shows this odd effect over a larger area (see below). In this shot, you can see the barchan dunes extend much further away from the mesas in the photo, as well as another larger mesa further east.

During the Paleozoic era, which lasted from 541 million to 251.9 million years ago, all these mesas were likely part of a single massive rock formation that has since been broken up by millennia of water and wind erosion, according to the Earth Observatory.

This formation may have been similar to the Richat Structure — a massive set of concentric rings of rock, also known as the "Eye of the Sahara," which is located in Mauritania around 285 miles (460 km) north of Guérou.

Mesas can be found across the globe but there is a particularly high concentration of them in the Sahara, as well as throughout parts of the U.S., such as Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Arizona, according to the National Park Service.

Elsewhere in the solar system, mesas are a prominent geological feature on Mars, having been carved out of the Red Planet by billions of years of wind erosion, according to Live Science's sister site Space.com.

For more incredible satellite photos and astronaut images, check out our Earth from space archives.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus