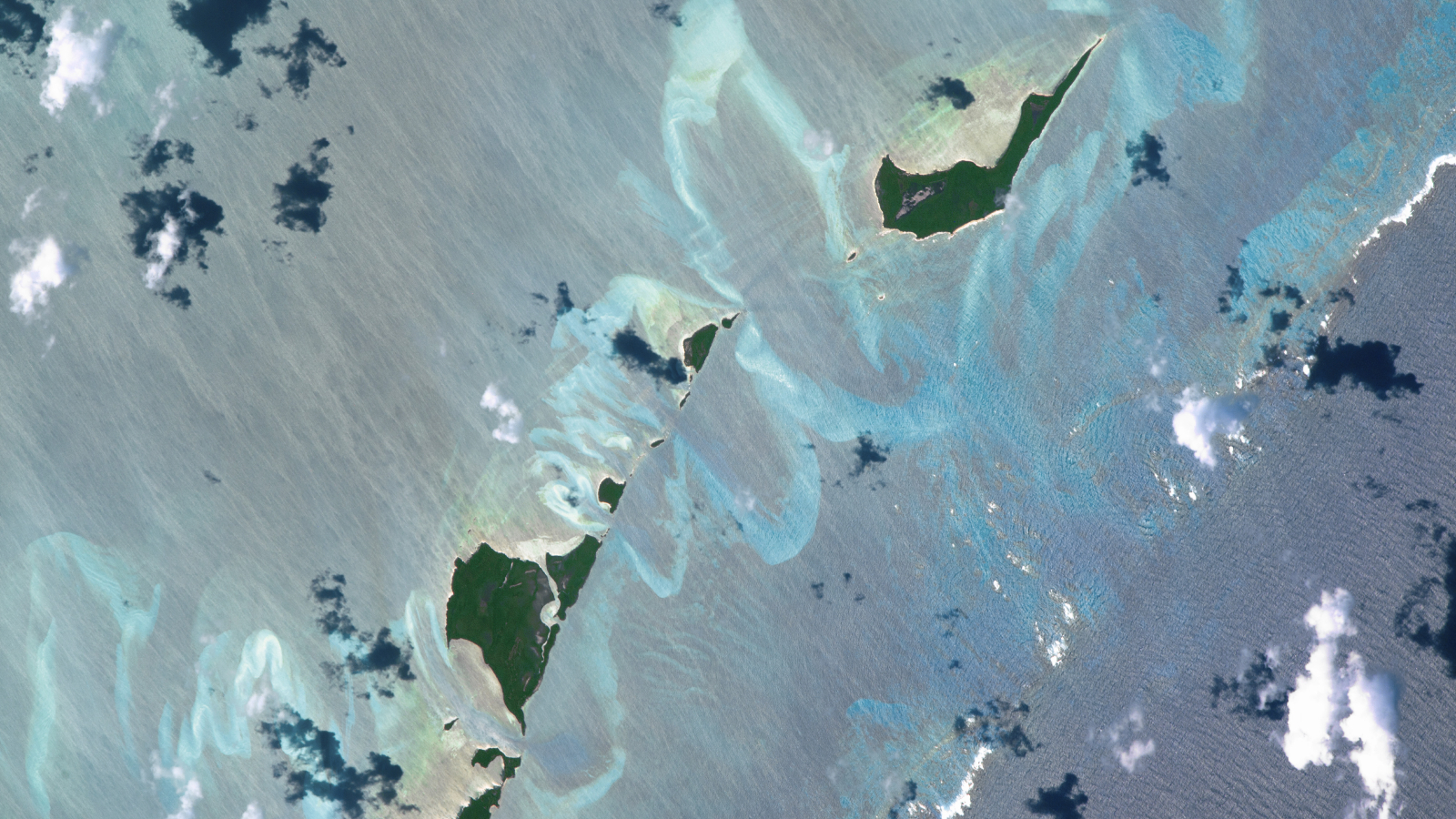

Submerged sandbanks shine like underwater auroras in astronaut's view of the Bahamas — Earth from space

A 2016 astronaut photo of the Bahamas shows a series of luminous, rippling sandbanks partly carved out by a coral reef. The image also reveals subtle differences in the ocean's surface caused by a steep, hidden ocean drop-off.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Where is it? Carter's Cays and Strangers Cay, the Bahamas [27.105580266, -78.06669135]

What's in the photo? Underwater sandbanks and a coral reef surrounding a pair of small islands

Who took the photo? An unnamed astronaut on the International Space Station (ISS)

When was it taken? Oct. 20, 2016

This intriguing astronaut photo shows off a series of rippling sandbanks surrounding a pair of small islands in the Bahamas. The submerged swirls were partly carved out by a coral reef lurking on the edge of a hidden ocean "drop-off."

The Bahamas is made up of more than 3,000 islands and smaller cays interspersed with coral reefs, fast-flowing tidal channels and shallow underwater structures, known as sand banks. These features collectively make the islands "one of the most recognizable places on Earth for astronauts," according to NASA's Earth Observatory.

This photo shows a series of intricate sandbanks and a shallow barrier-like coral reef in the waters surrounding two diminutive islands — Carter's Cays (lower left) and Strangers Cay (upper right). The islands are two of the northernmost landmasses in the Bahamas, located around 125 miles (200 kilometers) east of Florida. (For context, Strangers Cay is around 2.2 miles (3.6 km) across at its widest point.)

Article continues belowThe sand banks, which can be seen winding in and around the two cays like ribbons, have been sculpted by decades of unchanged ocean currents, causing sand to pile up in the same place over time.

But the coral reef — which cuts across the bottom right corner of the image and has waves breaking across its far edge — is much older, having likely built up over several millennia.

The largest and most prominent sandbank, which looks like a giant U-shape in the center of the image, lies directly opposite a large gap in the coral reef. This is no coincidence: The break in the reef has created a strong and sustained tidal flow that has pushed the sand much further backward, according to the Earth Observatory.

These sand swirls are fairly small compared with some of the larger sandbanks in the region. The biggest is the Great Bahama Bank, which covers an area of around 80,000 square miles (210,000 square kilometers) off the Exuma Islands in the central Bahamas and supports a massive seagrass ecosystem.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These features frequently draw comparisons to abstract paintings or the Northern Lights, due to their shape and captivating glow, when viewed from above. However, their supposed luminosity is actually just an optical illusion caused by their proximity to the ocean's surface. In some areas, the sand is likely only around 6.5 feet (2 meters) below the waves, according to the Earth Observatory.

If you look closely at the ocean's surface in the image, you will also notice that the water to the upper left of the islands is very light and covered with shimmering streaks, while the bottom right corner of the image — beyond the reef — is darker and exhibits traditional wave patterns.

This is the result of a steep drop-off in the deep ocean just beyond the coral reef, similar to the one depicted in the film "Finding Nemo." Beyond this point, ocean currents create the swells that many people see from the window of an airplane. But behind the reef, the wind sculpts the ocean's surface into subtle streaks instead.

This drop-off is also why there are no sandbanks visible beyond the reef.

For more incredible satellite photos and astronaut images, check out our Earth from space archives.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus