Astronaut snaps salty, pink Valentine's Day 'heart' shining in Argentina — Earth from space

A 2024 astronaut photo shows a striking pink, heart-shaped salt lake in the middle of the Argentine lowlands. The endearing photo was originally released to celebrate Valentine's Day.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Where is it? Salinas Las Barrancas, Argentina [-38.75293078, -62.95083234]

What's in the photo? A pink salt lake in the shape of a heart

Who took the photo? An unnamed astronaut on board the International Space Station (ISS)

When was it taken? Jan. 16, 2024

This amorous astronaut snap, first released by NASA on Valentine's Day 2025, highlights a pink, heart-shaped salt lake in Argentina.

Salinas Las Barrancas, sometimes known as Laguna de Salinas Chicas, is a shallow salt lake in the lowland plains of Argentina's Buenos Aires province, roughly 33 miles (53 kilometers) west of the port city of Bahía Blanca.

The lake bed is around 6 miles (10 km) across at its widest point and regularly fills with water after heavy rainfall. However, this liquid quickly evaporates due to the region's intense sunlight, exposing crystal-rich salt flats that are mined by local people, according to NASA's Earth Observatory.

Article continues belowIn this photo, the lake appears to be close to empty because of its lighter-pink hue, which is most likely the result of an imbalance between Dunaliella salina — a species of dark-red algae that thrives in most of Earth's salt lakes — and other microorganisms in the water, according to a 2022 Smithsonian magazine article about similarly colored salt lakes.

"We have rainy seasons, when the salinity levels decrease [because there's more water in the ponds]. When there's less salt, the Dunaliella survives and the ponds look brownish-red," Lilliam Casillas Martinez, a microbiologist at the University of Puerto Rico at Humacao, told Smithsonian magazine while explaining the colors of similar salt ponds in Puerto Rico. "During the dry season, it gets really salty. The Dunaliella dies and the archaea and bacteria take over. Then it becomes pink, pink, pink."

Locals mine up to 330,000 U.S. tons (300,000 metric tons) of salt from the flats of Salinas Las Barrancas twice a year, between the region's rainy seasons, according to a 2019 feature on the lake by Argentine news site La Nación. Most of this salt is replenished by the next major rainfall, and experts predict that mining will remain viable there for 5,000 years.

Mining is largely carried out using traditional processes, including scraping salt from the flats' surface with handheld tools. Workers must take precautions to protect their eyes and skin from intense sunlight that reflects off the pure white crystals. "The salt becomes part of your life," local worker Chepo told La Nación (translated from Spanish). "For someone else, it's a hellish place, but for me, the salt flats are my home; you get used to not being able to see."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Salinas Las Barrancas' high salinity means that not much can survive there. However, some salt-resistant vegetation does grow around the lake's edges, according to the Earth Observatory.

It is also home to colorful birds, including vibrant yellow cardinals (Gubernatrix cristata) and bright-pink Chilean flamingos (Phoenicopterus chilensis). These birds feed on tiny crustaceans that are rich in carotenoids — organic pigments synthesized by plants, algae and bacteria.

These specific carotenoids come from the Dunaliella algae, which the tiny crustaceans feed on, and naturally produce both red and yellow pigments. Without these pigments in their diets from birth, both bird species would be different colors; yellow cardinals are naturally red, while flamingos are born grayish-white.

See more Earth from space

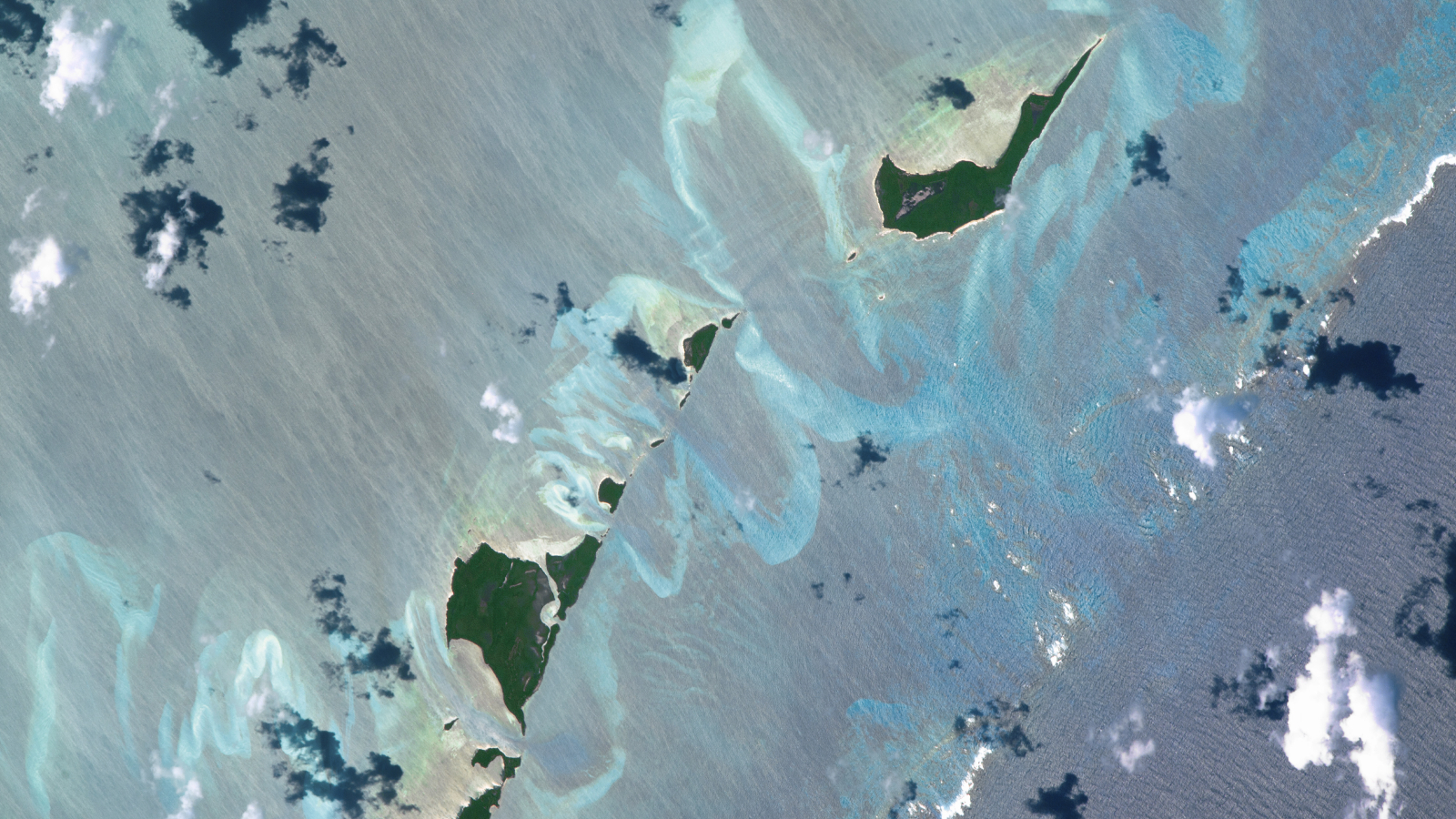

A 2016 astronaut photo of the Bahamas shows a series of luminous, rippling sandbanks partly carved out by a coral reef. The image also reveals subtle differences in the ocean's surface caused by a steep, hidden ocean drop-off.

A 2021 astronaut photo shows a triple valley system in Argentina's Los Glaciares National Park where a massive climate-resilient glacier, a pristine turquoise lake and a murky green "river" come together at a single point.

A 2025 satellite image shows a series of ghostly ice swirls sculpted on the surface of Lake Michigan by strong winds during an extreme cold snap that covered Chicago in a blanket of snow.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus