Trippy 'biomass' snap reveals first detailed look at our planet's carbon stores — Earth from space

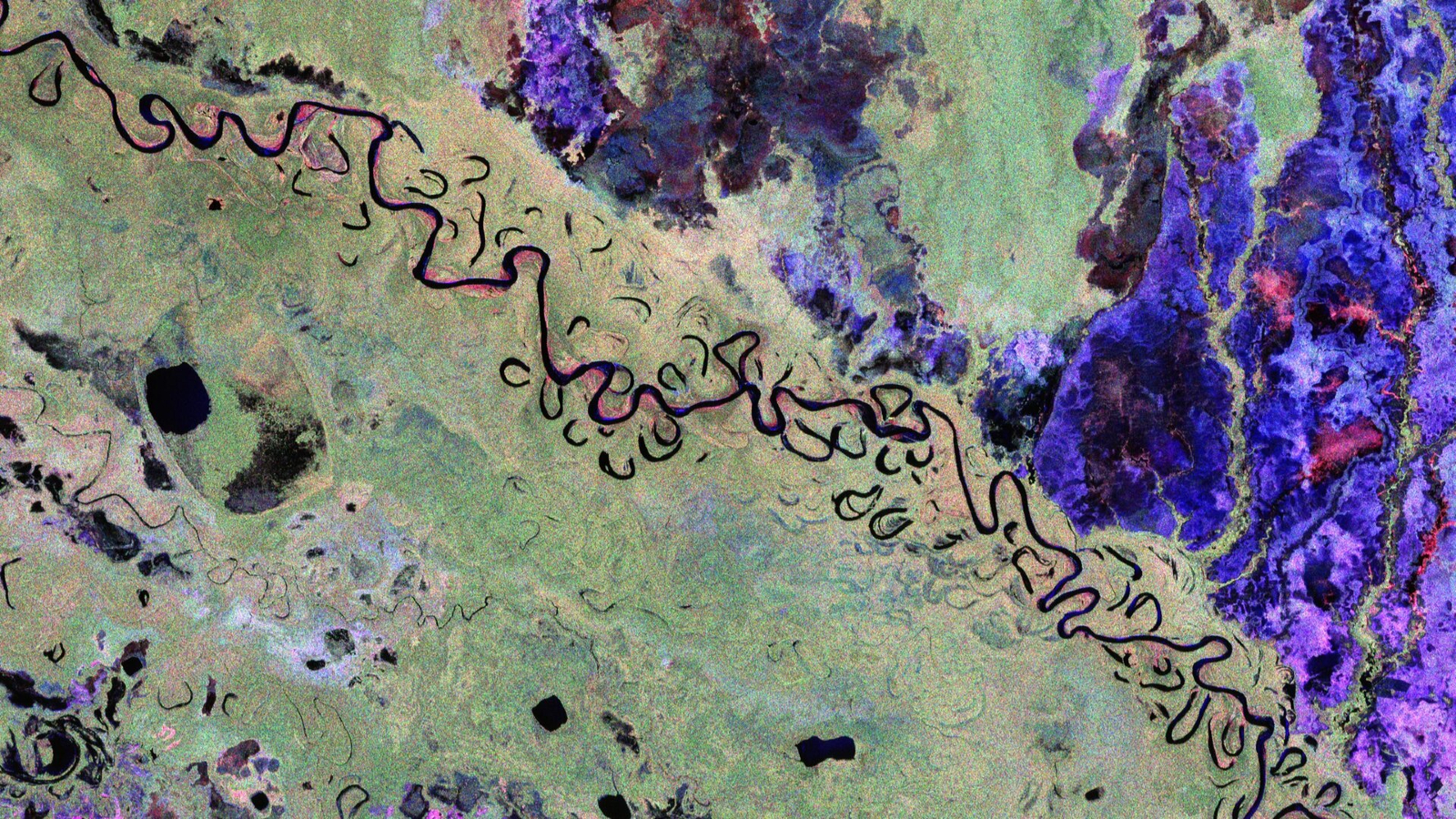

The first false-color image from ESA's newly operational Biomass satellite shows off a unique perspective of the rainforests, grasslands and wetlands surrounding a winding river in Bolivia.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Where is it? Beni River, Bolivia [-11.23789979, -66.2670646]

What's in the photo? False colors representing the varying levels of biomass around the river

Which satellite took the photo? The European Space Agency's Biomass satellite

When was it released? June 23, 2025

This trippy satellite snap shows the hidden intricacies of the biomass, or carbon-rich material, surrounding a winding river in Bolivia. The first-of-its-kind image, snapped last year, shows the unique orbital perspective from one of Europe's newest spacecraft.

The striking photo shows a section of land — around 56 miles (90 kilometers) long and 37 (60 km) wide — surrounding the Beni River (or Rio Beni) in northern Bolivia. The convoluted waterway stretches approximately 680 miles (1,095 km) from its origin in the Andes, just north of La Paz, and into Brazil, where it merges with the Amazon River.

The image was snapped by the European Space Agency's (ESA) Biomass satellite, which launched April 29, 2025. This satellite scans Earth's surface using polarized radar, allowing it to detect subtle differences in biomass across the landscape.

In the image, rainforests appear green, grasslands are purple, wetlands are reddish, and the river and nearby lakes appear black. (The photo has also been flipped so that north is to the right of the photo.)

The mission's "first images are nothing short of spectacular — and they're only a mere glimpse of what is still to come," Michael Fehringer, an ESA scientist and Biomass project manager, said in a statement when the image was released.

One key goal of the Biomass satellite is to measure how Earth's carbon-rich areas are shifting in response to human pressures, such as climate change and deforestation.

For example, Bolivia is among the countries hit hardest by deforestation. But it is hard to quantify the scale of this issue using normal satellite photos, where forests, grasslands and wetlands appear to merge (see above).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

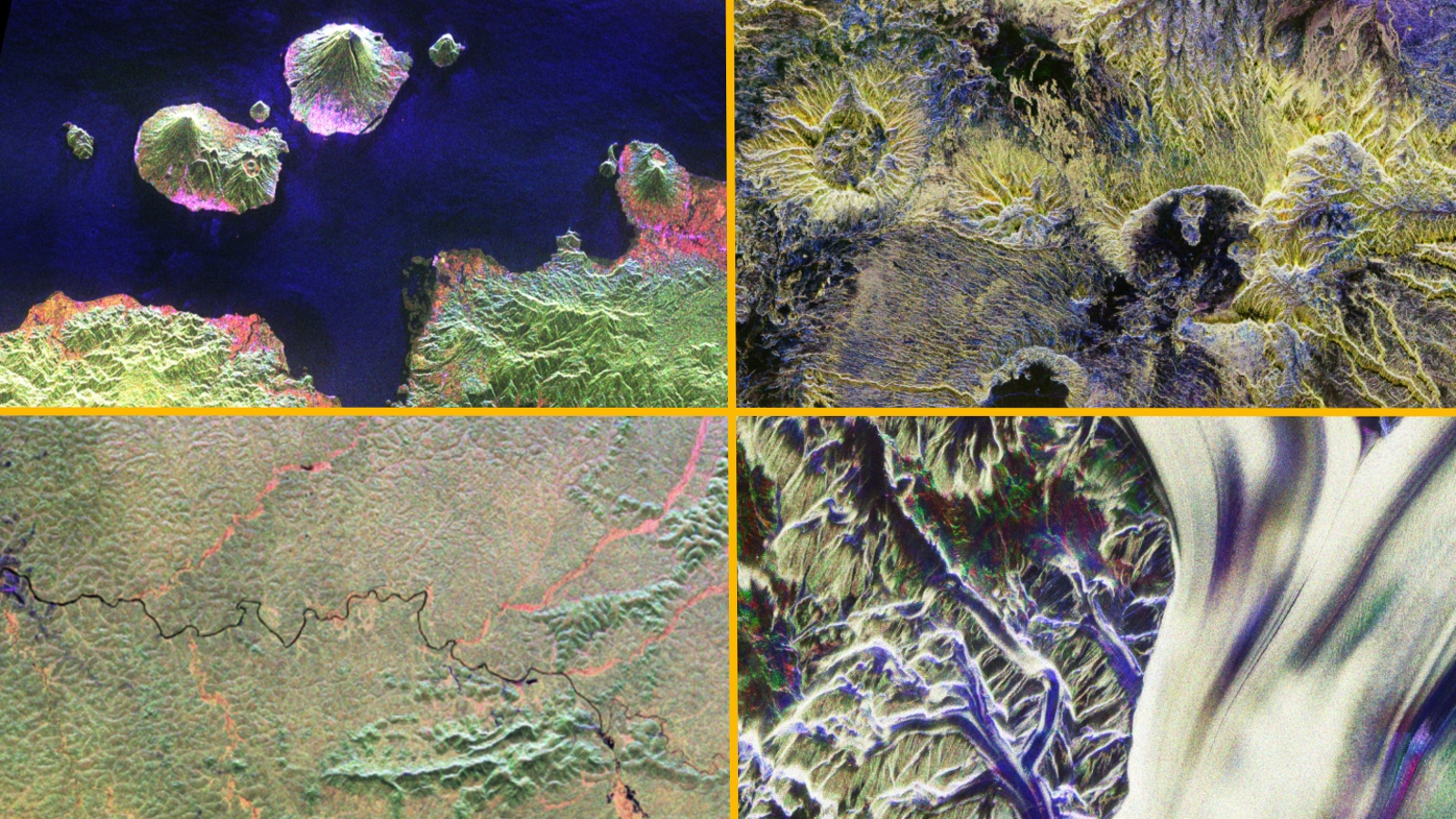

ESA has since revealed several more stunning images from the Biomass satellite, including snaps of Mount Gamkonora in Indonesia, the Ivindo River in Gabon, the Tibesti Mountains in Chad and the Nimrod Glacier in Antarctica.

The satellite is now fully online and will scan the entirety of Earth's forests every six months.

Biomass's radar technology will also be particularly good at penetrating and assessing ice masses, which will be an important secondary goal of the spacecraft's mission.

On Jan. 26, ESA announced that it is opening up the satellite's dataset to the public, which will allow for more research. This collaborative approach will "unlock vital insights into carbon storage, climate change, and the health of our planet's precious forest ecosystems," Simonetta Cheli, ESA's director of Earth observation programs, said in the statement.

See more Earth from space

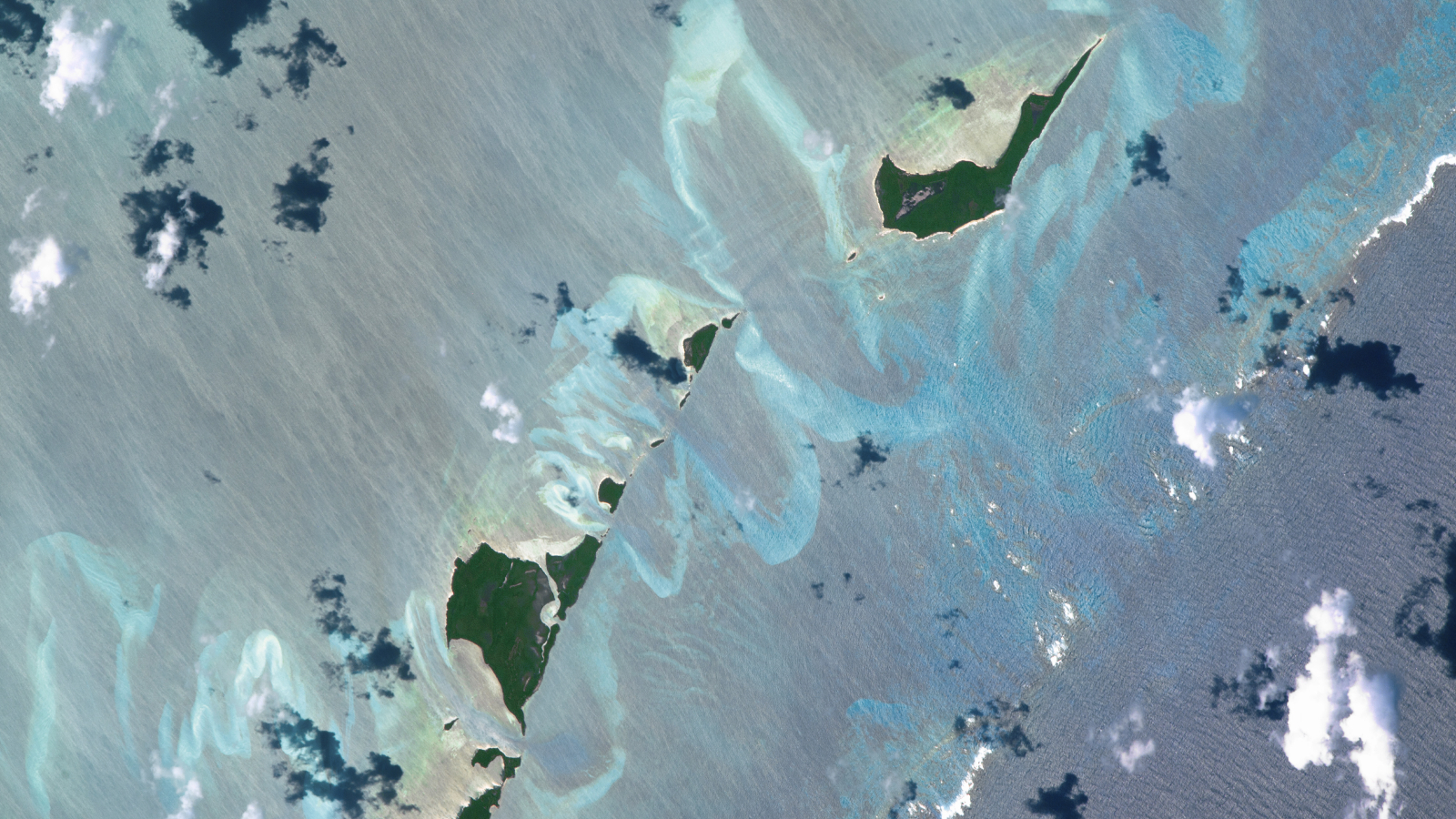

A 2016 astronaut photo of the Bahamas shows a series of luminous, rippling sandbanks partly carved out by a coral reef. The image also reveals subtle differences in the ocean's surface caused by a steep, hidden ocean drop-off.

A 2021 astronaut photo shows a triple valley system in Argentina's Los Glaciares National Park where a massive climate-resilient glacier, a pristine turquoise lake and a murky green "river" come together at a single point.

A 2025 satellite image shows a series of ghostly ice swirls sculpted on the surface of Lake Michigan by strong winds during an extreme cold snap that covered Chicago in a blanket of snow.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus