How can deserts form next to oceans?

Deserts are notoriously dry, so why do so many of them border oceans?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

When you picture a desert, you probably imagine a vast, empty landscape far from any water. But surprisingly, some of the driest places on Earth lie right beside the ocean. Both the Atacama, in Chile, and the Namib, in southern Africa, stretch along coastlines. So how did these extreme deserts form in places bordered by so much water?

There are three main factors that allow deserts form next to oceans, David Kreamer, a hydrologist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, told Live Science: how air moves vertically, how air moves horizontally, and how mountain ranges interact with air moisture.

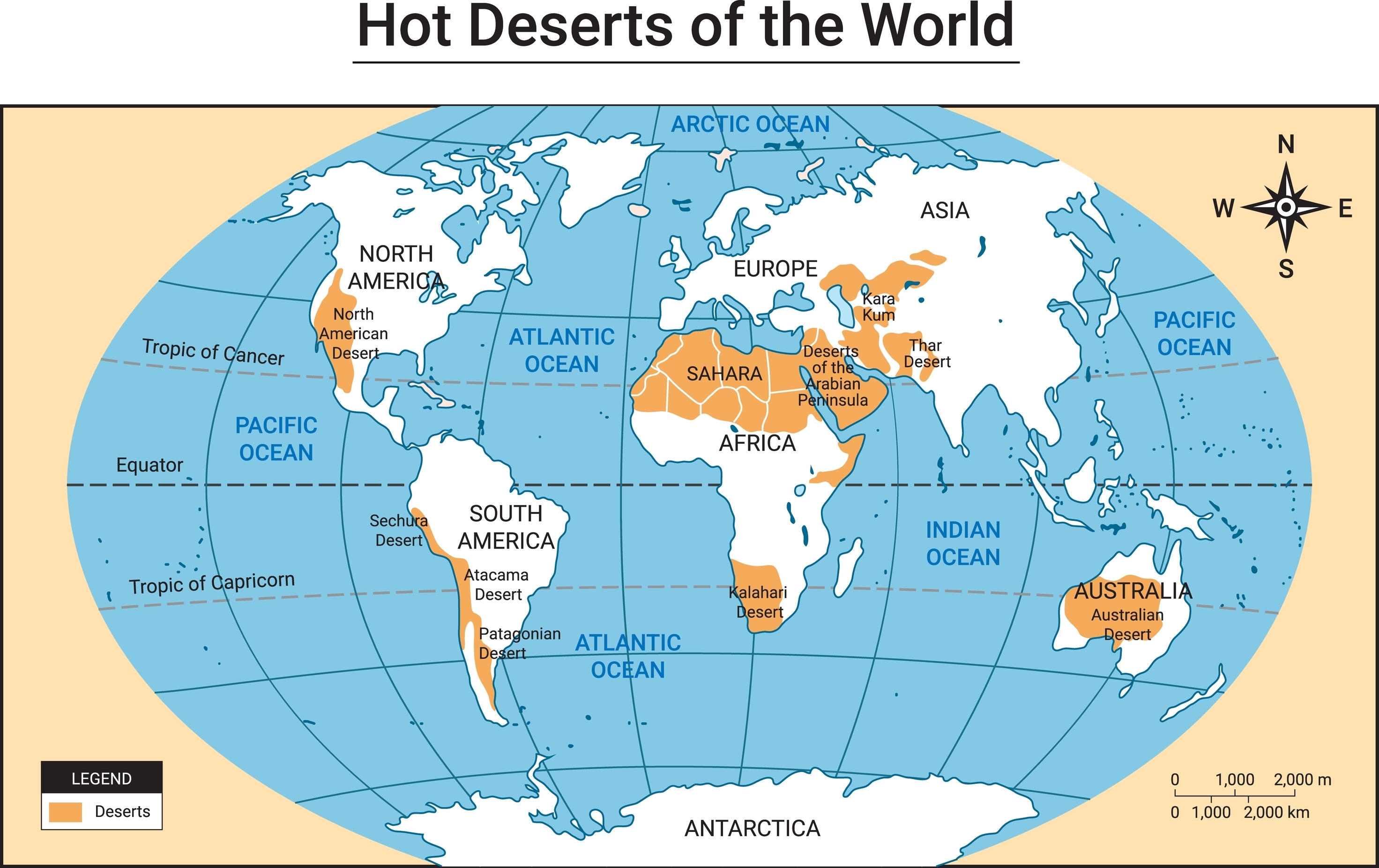

If you look at a world map, you'll notice that most deserts sit above or below the equator. That's because the equator receives the most direct sunlight and causes the air to warm and rise. As the warm air rises, it creates a low-pressure system — a region where atmospheric pressure is lower than its surrounding area, Kreamer explained. Any moisture in the air cools and condenses into clouds and rain. That's why the regions along the equator are home to lush forests, like the Amazon.

Sign up for our weekly Life's Little Mysteries newsletter to get the latest mysteries before they appear online.

That rising air spreads outward and sinks between 20 and 40 degrees north and south of the equator, and suppresses cloud formation — which explains why there are so many deserts along the subtropical belt, such as the Sahara and the Kalahari.

Then, there is the horizontal movement of air across the planet. Near the equator, trade winds blow from east to west. These winds tend to drop moisture on the eastern sides of continents, leaving their western sides drier. In the case of the Namib, for example, when it does rain, that rain doesn't fall in the desert itself but rather in the mountains to the east, said Abi Stone, a physical geographer at the University of Manchester in England.

Cold ocean currents also play a role. The air that's being blown across the cold current cools on contact with it and picks up some of its moisture, and because of the coldness, the air becomes quite stable. "We kind of envisage packages of air, in some ways, like a balloon, because they don't totally mix, but the balloon skin is really flexible, and they can expand and contract," Stone told Live Science. "The cold air won't tend to do much of that expansion." Without any convection, the pack of air becomes trapped, unable to rise. "But what it can do is hold some moisture, and at the low level, that can get blown on land, and you end up with quite foggy environments at the western part of those coastal deserts," Stone said.

The presence of mountains impacts the dryness of these deserts as well. When moist air is forced over a mountain range, it cools and drops rain on the windward side, Kreamer explained. By the time the air descends on the leeward side, much of its moisture is gone, creating a rain shadow, or an area by the mountains that gets reduced rain. For instance, Seattle, which is located on the western side of the Cascade Mountains, gets an average of 39.3 inches (99.8 centimeters) of rain a year, while Yakima, located on the eastern side of the Cascades, gets an average of 8 inches (20.3 cm) of rain annually.

In the case of the Atacama, Kreamer said, "the wind that comes in South America drops a lot of rain on the east side over the Amazon, and then it hits the Andes. The Andes sap more water off the wind and then right along the coast of South America on the west side, where Chile is," leaving the Atacama exceptionally dry.

These factors give coastal deserts unique characteristics that aren't found in other deserts. They tend to have cooler and more stable climates than inland deserts do, and they're home to plants and animals that have evolved special traits to capture moisture. In the Namib, for example, some beetles harvest water by pointing their butts toward the foggy air.

"People have studied what that surface looks like to make more effective fog nets," Stone said. "There are some amazing creatures."

The formation of polar deserts, like most of Antarctica and the northernmost parts of the Arctic, is driven by many of the same factors as warm coastal deserts. The temperature also plays a role, since the air is so cold in these parts of the world that it can't hold moisture. "In the case of Antarctica, the strong winds and ocean current around the continent is effective at blocking weather systems traveling onto the continent," Stone said.

Equator quiz: Can you name the 13 countries that sit on Earth's central line?

Sara Hashemi is a journalist and fact-checker covering environmental justice, climate and the intersection between science and society. Her work has appeared in Sierra, Smithsonian Magazine, Maisonneuve and more. She has a master's degree in science journalism from NYU.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus