Mega-iceberg A23a, formerly the world's largest, turns into bright 'blue mush' as it finally dies after 40 years at sea

New satellite photos reveal that one of the world's largest and longest-lived icebergs, A23a, has developed vibrant blue striations on its surface. The striking snaps hint that the "megaberg" will soon disappear forever, ending a surprisingly eventful four-decade-long saga.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The world's formerly largest iceberg, A23a, has been transformed into a beautiful blob of stripy "blue mush," signaling its imminent demise, new satellite photos reveal. The dying ice mass, which until recently was three times larger than New York City, is one of the oldest bergs on record, now nearing its 40th birthday.

A23a is an oddity among icebergs. The megaberg, dubbed the "queen of icebergs," broke off from Antarctica's Filchner-Ronne Ice Sheet in the summer of 1986, but quickly became stuck in place when its submerged bottom caught on the seafloor. It remained trapped for most of the last four decades, barely shrinking in size due to its close proximity to its parent ice shelf. However, A23a finally broke free from its seafloor tether in 2020 and began drifting away from Antarctica.

Its subsequent journey has been eventful. First, the hefty ice mass was trapped again, this time in a massive ocean current, or gyre, which caused it to spin in place for months. Then, after breaking free from the vortex in December 2024, the dizzy berg made a beeline for the island of South Georgia, sparking fears among researchers that it would ground again and trigger a potential ecological disaster for the island's resident penguins. However, this worst-case scenario was avoided when A23a began to break apart in May 2025, shortly before reaching the island.

Article continues belowSince then, the largest remaining chunk of the iceberg has drifted further north into the South Atlantic Ocean, where warmer waters circulating down from South America are taking their toll.

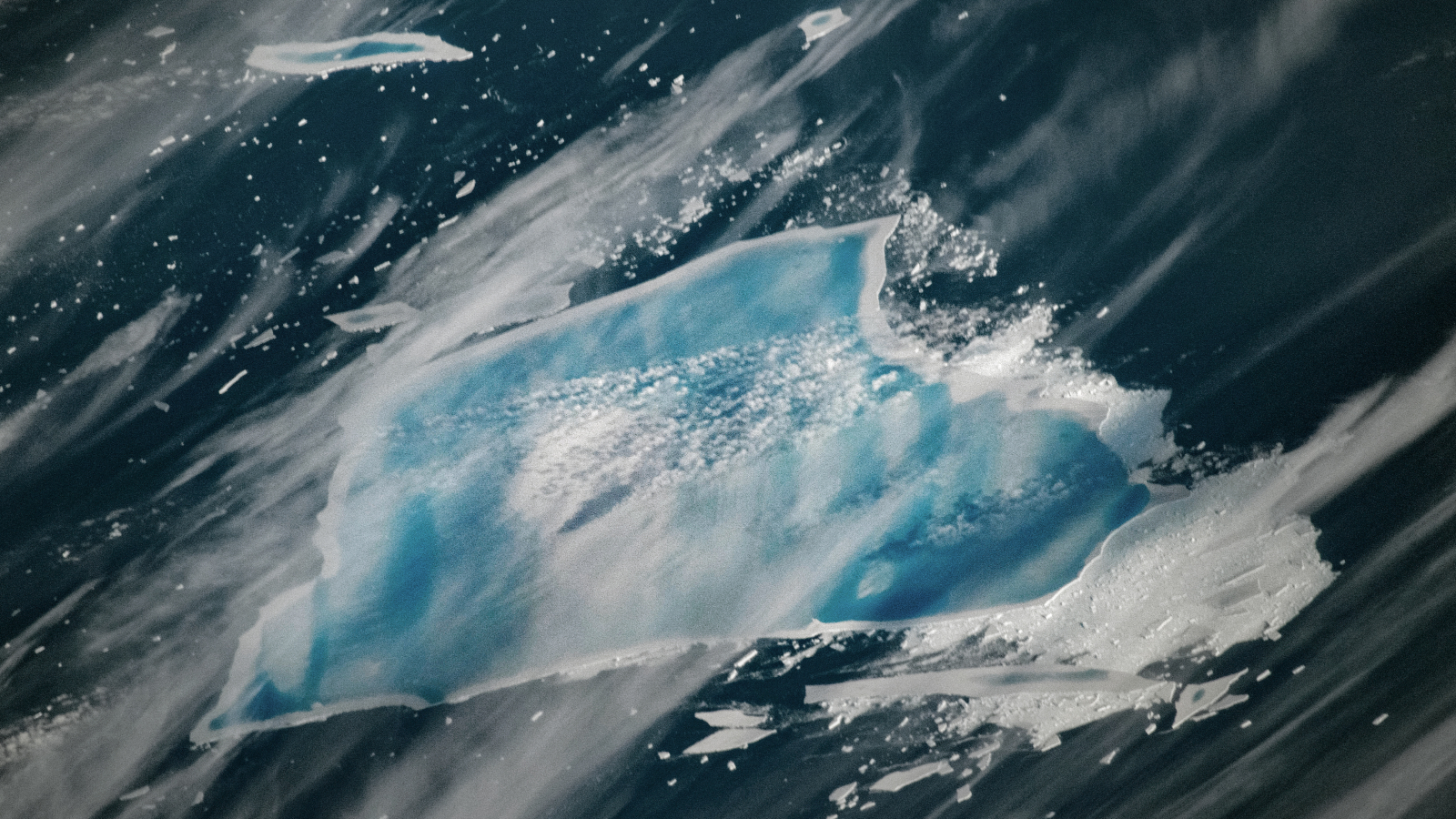

New photos, captured on Dec. 26 by NASA's Terra satellite, reveal a completely unrecognizable version of A23a. The iceberg, which is now around a third of its original size, is shown covered with pools of blue water encircled by thick borders of white ice, dubbed "ramparts." In the image, A23a is also flanked by a pool of gray sludge, known as ice melange, which has likely leaked out from under the iceberg. It is also further surrounded by hundreds of smaller bergs that have broken off its edges.

A23a was around three times the size of New York City before its run-in with South Georgia last year.

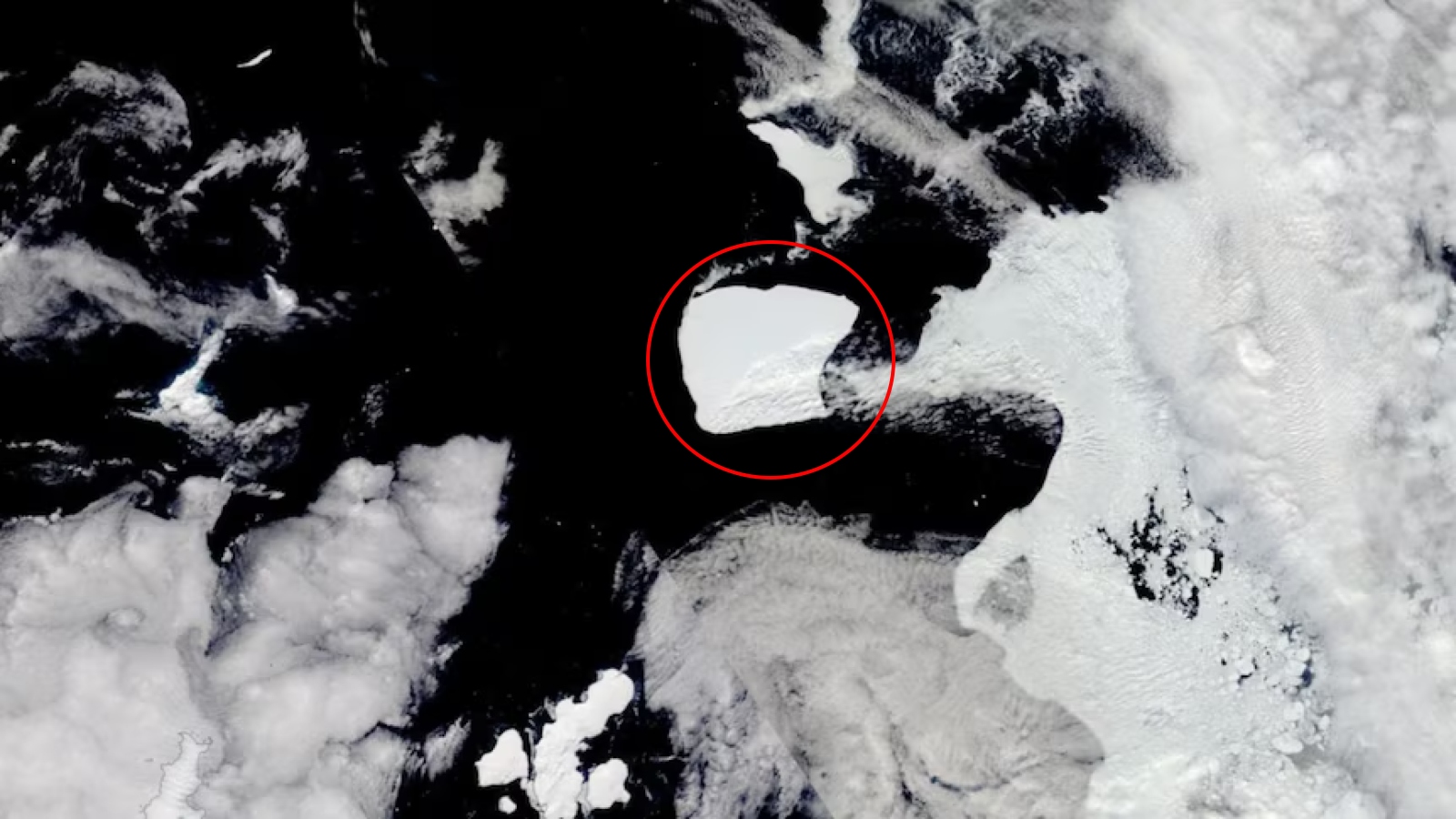

A23a (circled) was previously trapped just offshore from Antarctica's Filchner-Ronne Ice Sheet between 1986 and 2020.

Large chunks have been breaking off from A23a for months as it's moved into warmer waters.

A23a temporarily became stuck off the coast of South Georgia, but quickly began to break apart before moving further North.

The "blue mush" visible on A23a is made up of melt ponds, which form when surface ice loses its structural integrity, Ted Scambos, a climate scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder, said in a NASA statement. These ponds align into streaks, likely caused by the "weight of the water sitting inside cracks in the ice and forcing them open," Scambos added.

The cracks likely run parallel to grooves on the iceberg's underside, which were carved into the ice by centuries of movement over the ground while still attached to the Filchner-Ronne Ice Sheet, Walter Meier, a senior research scientist at the National Snow & Ice Data Center (NSIDC), said in the statement. "It's impressive that these striations still show up after so much time has passed," added Chris Shuman, a retired glaciologist formerly with the University of Maryland.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The vibrant striations may have already started to disappear, according to another photo, snapped on Dec. 27 by an unnamed astronaut onboard the International Space Station. This subsequent image shows a more uniform pool of blue water on the iceberg's surface (see below).

It is currently unclear how much of A23a remains or if it has already begun to disappear fully.

Due to its persistent massive size, A23a has repeatedly held the title of "world's largest iceberg" throughout its long lifespan.

It most recently regained the title in June 2023, when the previous largest iceberg, A-76A, broke apart; then, it lost the accolade again in September 2025, shortly after its encounter with South Georgia. (Some outlets have misreported that A23a remains the world's largest iceberg, likely due to an outdated page from Guinness World Records.)

The world's current largest iceberg is now D15A, which has a surface area of around 1,200 square miles (3,100 square kilometers), according to NSIDC, making it a few hundred square miles smaller than A23a at its peak.

For more incredible satellite photos and astronaut images, check out our Earth from space archives.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus