Scientists discover 85 'active' lakes buried beneath Antarctica's ice

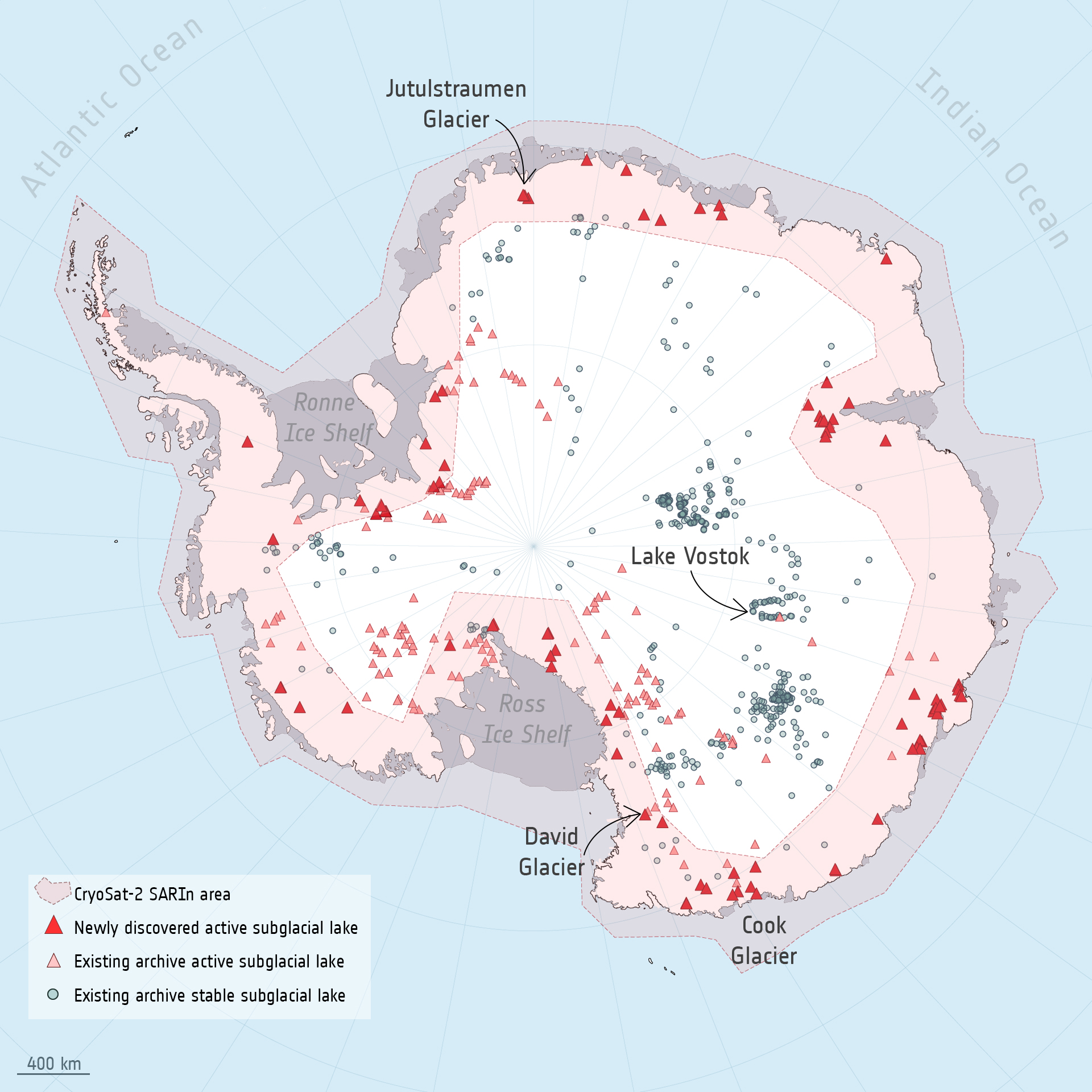

Data from ESA's Cryosat-2 satellite has revealed 85 never-before-seen, active subglacial lakes buried beneath Antarctica's ice — 58% more than were previously known.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists have identified 85 previously unknown lakes hidden beneath Antarctica's ice using a decade's worth of satellite data.

The newfound lakes are "active," meaning they periodically drain and refill, changing size and shape over months and years, the researchers said. This subglacial activity affects the stability of glaciers and their grinding movement over the Antarctic bedrock, which in turn could impact global sea levels, the team noted.

"It was fascinating to discover that the subglacial lake areas can change during different filling or draining cycles," study co-author Anna Hogg, a professor of Earth observation at the University of Leeds in the U.K., said in a statement from the European Space Agency (ESA). "This shows that Antarctic subglacial hydrology is much more dynamic than previously thought, so we must continue to monitor these lakes as they evolve in the future."

Before this latest discovery, 146 active subglacial lakes were already known in Antarctica. The new study brings the total number of active lakes to 231 and adds to scientists' understanding of when and how subglacial lakes drain and refill, study lead author Sally Wilson said in the statement.

"It is incredibly difficult to observe subglacial lake filling and draining events," said Wilson, who is a doctoral student in the Institute for Climate and Atmospheric Science at the University of Leeds. "Only 36 complete cycles, from the start of subglacial filling through to the end of draining, had been observed worldwide before our study. We observed 12 more complete fill-drain events, bringing the total to 48."

Subglacial lakes are pools of meltwater that form when geothermal heat from Earth's interior rises to the base of an ice sheet, or when enough frictional heat is generated by ice grinding on the bedrock. Subglacial lakes can sometimes periodically drain, creating a flow of water that lubricates the bottom of the ice sheet and helps it slide on the bedrock, accelerating the movement of ice toward the ocean.

For the study, the researchers analyzed data captured between 2010 and 2020 from ESA's Cryosat-2 satellite, which measures variations in the thickness of sea ice, glaciers and ice sheets worldwide. Cryosat-2 carries an instrument called a radar altimeter that can detect small changes in the height of ice features, including changes resulting from lakes draining and filling at the base of the ice.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The data revealed dozens of locations where the Antarctic Ice Sheet is sinking and rising slightly as a result of meltwater draining and refilling subglacial lakes beneath the surface. The observations also showed 25 clusters of lakes and five never-before-seen subglacial lake networks with interconnected drain-and-refill cycles, the researchers wrote in the study, which was published Sept. 19 in the journal Nature Communications.

The results are important because they improve scientists' understanding of ice sheet dynamics and how these impact global sea levels, which could help researchers design more accurate climate and Earth models. "The numerical models we currently use to project the contribution of entire ice sheets to sea level rise do not include subglacial hydrology," Wilson said. "These new datasets of subglacial lake locations, extents, and timeseries of change, will be used to develop our understanding of the processes driving water flow beneath Antarctica."

Some subglacial lakes in Antarctica are stable, meaning they do not drain and refill. An example is Lake Vostok, which sits beneath the East Antarctic Ice Sheet and holds more than enough water to fill the Grand Canyon, according to the statement. If Lake Vostok ever started emptying, it could affect the entire ice sheet and cause global sea levels to rise, the researchers noted.

"The more we understand about the complex processes affecting the Antarctic Ice Sheet, including the flow of meltwater at the base of the ice sheet, the more accurately we will be able to project the extent of future sea level rise," Martin Wearing, a digital twin Earth scientist and ESA's Polar Science Cluster coordinator, concluded in the statement.

Antarctica quiz: Test your knowledge on Earth's frozen continent

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus