In a 'race against time,' archaeologists uncovered Roman-era footprints from a Scottish beach before the tide washed them away

Archaeologists raced against the tide to record a unique set of footprints made 2,000 years ago on a Scottish beach.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

While walking their dogs along a cliff-flanked Scottish beach after an intense storm, a couple stumbled upon a series of unusual markings on the damp ground — patterns that looked like ancient human and animal footprints.

Their discovery sparked an archaeological race against the clock to document and study the prints before they disappeared into the surf.

"It's very rare that you get involved in a genuine archaeological emergency where, if we didn't do it very, very quickly, the whole site would be gone," Kate Britton, an archaeologist at the University of Aberdeen, said in a video about the find.

On the beach at Lunan Bay in eastern Scotland, locals Ivor Campbell and Jenny Snedden — along with their dogs Ziggy and Juno — spotted a fresh layer of clay in the storm-damaged dunes with what appeared to be prints. They notified Aberdeenshire council archaeologist Bruce Mann, who brought in Britton and her team to excavate the newly uncovered site before it was lost forever.

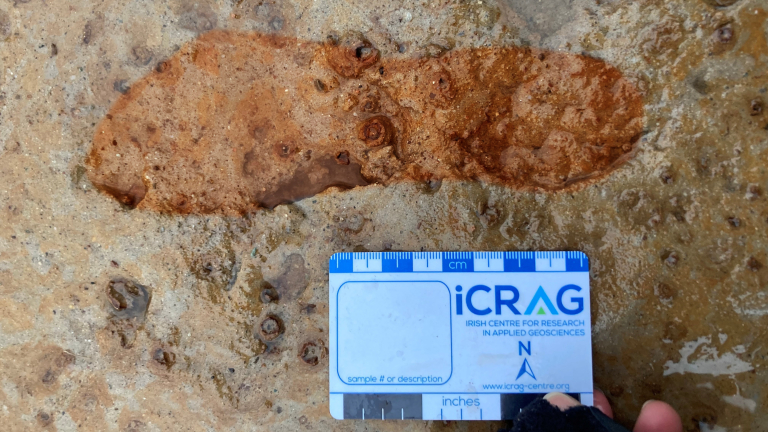

The team of archaeologists worked in wind gusts up to 55 mph (88.5 km/h), racing to document the prints as the site was eroded with each high tide. They used drones, cameras and, later in the lab, 3D modeling software to record images of the archaeological site. They also used plaster to create molds of some of the better-preserved prints, which were made by barefoot humans and several animals, including red deer (Cervus elaphus) and roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), according to the statement.

"I'd never seen a site like this in Scotland," Britton said. "It was just immediately clear that this was something special."

Underneath the prints, the archaeologists found a layer of charred plant remains. They carbon-dated the plants to 2,000 years ago, during the late Iron Age.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The late Iron Age dates are in keeping with what we know about the rich archaeology of nearby Lunan Valley," Gordon Noble, an archaeologist at the University of Aberdeen, said in the statement. "It's very exciting to think these prints were made by people around the time of the Roman invasions of Scotland and in the centuries leading up to the emergence of the Picts."

The Lunan Bay site "tells us how this now sandy beach was once a muddy estuary and that humans were using this environment, perhaps for hunting deer or to collect wild plant foods," William Mills, an archaeologist at the University of Aberdeen, said in the statement.

Britton and her team excavated the site for two days, recording as much as they could. When they returned a week later, the prints were completely gone.

"Footprints that represent actions of people over minutes, thousands of years ago, were destroyed within days," Britton said.

Although the Lunan Bay site is unique in Scotland, Britton said, "what it does mean for us now is there could be potentially other sites like this out there."

This footprint find is exciting because trackways can reveal much about the people who left them, including their approximate weight, height and age, as well as how fast they were walking and if they were wearing shoes. They can even reveal behavior; for example, footprints left at White Sands National Park in New Mexico appear to have been left by ice age children who had jumped in muddy puddles. In Portugal, 78,000-year-old footprints left by Neanderthals suggest that a man, child and toddler had been foraging for food, practicing ambush hunting or stalking prey, as some of the footprints overlapped those of large mammal tracks.

We look forward to any further analyses of these footprints from Scotland and what they might tell us about the Iron Age people who lived there.

Roman Britain quiz: What do you know about the Empire's conquest of the British Isles?

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus