Scientist accidentally stumbles across bizarre ancient ‘wrinkle structures’ in Morocco that shouldn't be there

Ancient fossil structures imprinted on rocks that were once deep beneath the ocean suggest the search for the first life on Earth needs to be broadened.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Newly discovered fossil imprints of ancient microbial colonies suggest that researchers need to broaden their search for the oldest life to deeper and more unstable areas.

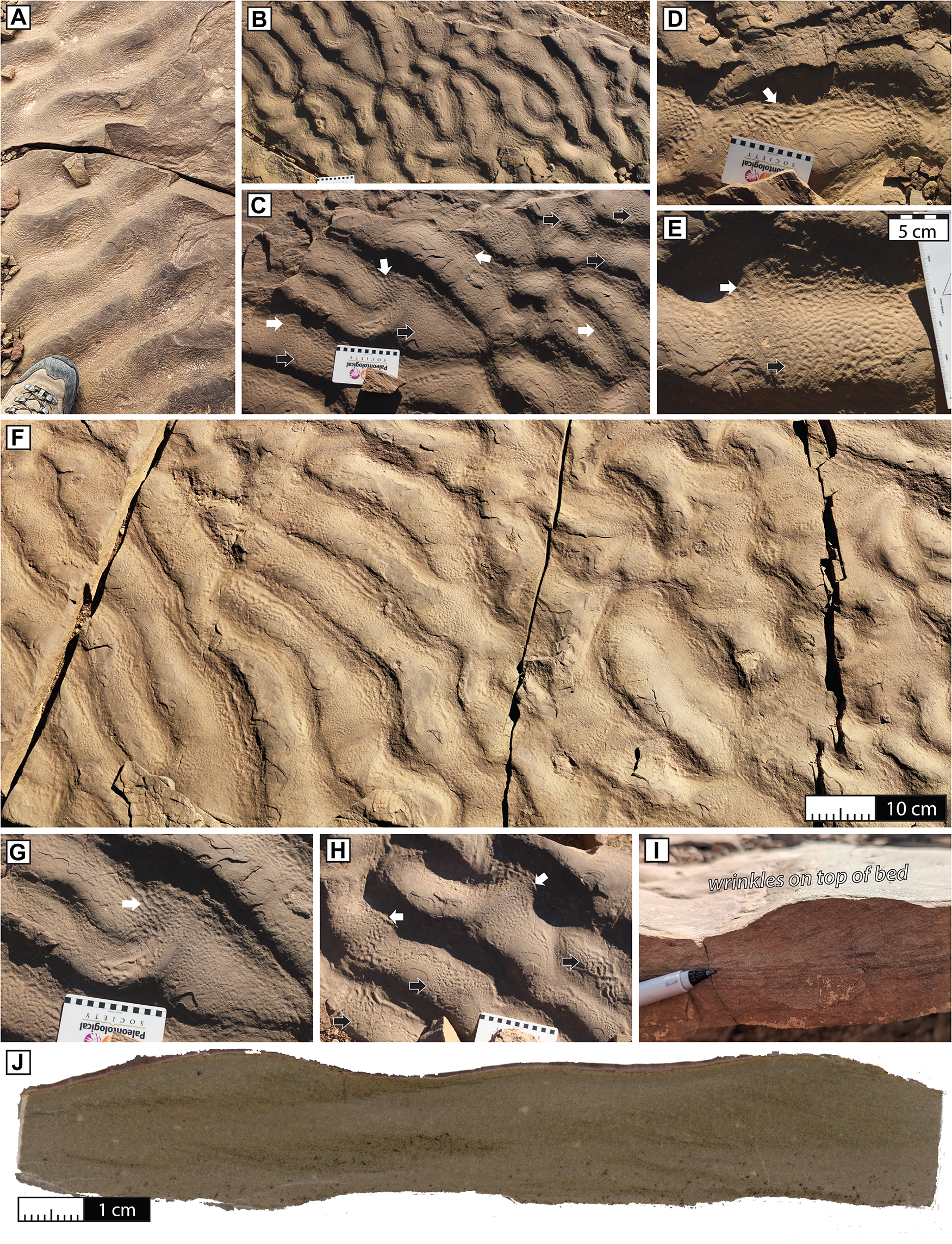

The wrinkled fossil structures, found in the Central High Atlas Mountains of Morocco, are imprinted on turbidites, which are deposits laid down by underwater landslides. The researchers were surprised to see the imprints on these turbidites, because most microbial mats today grow in shallow water, where photosynthetic bacteria can draw energy from light filtering through the waves.

The turbidites in Morocco, on the other hand, were at least 590 feet (180 meters) below the surface when they were laid down 180 million years ago.

Article continues belowWrinkle structures "shouldn't be in this deep-water setting," Rowan Martindale, a geobiologist at the University of Texas at Austin, said in a statement.

Martindale is the lead author of a paper published Dec. 3 in the journal Geology describing this surprising find. She stumbled — almost literally — across the fossils while studying ancient reefs in Morocco's Dadès Valley. While walking, she noticed wrinkly, ripple-like structures on the fine sandstone and siltstone below her feet.

These wrinkle structures looked like imprints of photosynthetic microbial mats, which are layered communities of bacteria that often form on sediments in ponds, oceans and other bodies of water. But those fossils are usually older than 540 million years because the delicate pattern is normally wiped away by animal activity over time, and there were few animals before 540 million years ago.

The fossils also couldn't have been photosynthetic, the researchers reported in their paper, because very little light would have penetrated the water to their level. However, chemical analysis revealed high levels of carbon in those rock layers — a sign that the wrinkles were formed by life.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This life was likely chemosynthetic, meaning it got its energy via chemical reactions rather than from sunlight, Martindale and her colleagues wrote. Instead, these organisms would have lived off of sulfur or other compounds. Today, chemosynthetic microbial mats form on continental shelves, where underwater landslides and turbidites also occur.

Those landslides may have been crucial to the cycle that allowed the microbes to thrive, the researchers found. Landslides tumbling from the continent toward the deep ocean would have dragged down organic material, which would have decomposed and created compounds such as methane or hydrogen sulfide — tasty snacks for chemosynthetic life. Between landslides, microbial mats would have thrived. Sometimes, they would have been washed away by another debris flow, but in other cases, their traces were preserved.

The finding suggests that scientists should widen their search for signs of wrinkle structures from shallow formations to rocks that were originally formed in deeper waters. This may lead them to more information about the oldest chemosynthetic organisms.

"Wrinkle structures," Martindale said, "are really important pieces of evidence in the early evolution of life."

Martindale, R. C., Sinha, S., Stone, T. N., Fonville, T., Bodin, S., Krencker, F.-N., Girguis, P., Little, C. T. S., & Kabiri, L. (2025). Chemosynthetic microbial communities formed wrinkle structures in ancient turbidites. Geology, 54(2), 173–178. https://doi.org/10.1130/g53617.1

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus