The largest reservoir of hydrogen on Earth may be hiding in its core

Earth's core contains nine to 45 times more hydrogen than the planet's oceans do, according to a new study that could settle a debate about when and how hydrogen was delivered to Earth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Earth's core contains up to 45 times more hydrogen than the oceans do, making it the largest hydrogen reservoir on the planet, a new study suggests.

Researchers found that this vast amount of hydrogen entered the core during its formation around 4.5 billion years ago, and did not arrive via comets that pummeled Earth once the core was established. The finding could settle the debate about when and how hydrogen was delivered to our planet.

"That hydrogen on Earth, including hydrogen in the core, was delivered during planet formation is an established hypothesis," study lead author Dongyang Huang, an assistant professor in the School of Earth and Space Sciences at Peking University in China, told Live Science in an email. "What differentiates the community is when hydrogen was delivered along Earth's formation."

Article continues belowThis debate has continued because hydrogen deep inside Earth is extremely difficult to quantify. Hydrogen is the smallest and lightest element in the universe, so most techniques do not have the resolution to properly detect it in high-pressure and high-temperature environments such as Earth's core.

But estimating how much hydrogen is locked inside the core is a key to understanding how the hydrogen got there in the first place, Huang said.

Previous research used a technique called X-ray diffraction to estimate the amount of hydrogen in Earth's core. This method quantifies the minerals and other substances in a material by analyzing how that material scatters X-rays. Because Earth's core is made almost entirely of iron, scientists added hydrogen to a sample of iron in the lab and measured the expansion of the iron's crystal structure to calculate how much hydrogen could be trapped inside the core.

The downside of X-ray diffraction in this case is that it makes a couple of crucial assumptions, Huang said. First, it assumes researchers have an accurate understanding of iron crystal structures and how they react under certain conditions. Second, it supposes that silicon and oxygen, both present in the core, do not deform the crystal structure when they dissolve into iron — which, it turns out, they do.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For the new study, Huang and his colleagues employed an alternative method known as atom probe tomography. This technique can "provide 3D nanoscale compositional mapping of all the elements in the periodic table" and is "ideal for high-pressure samples," Huang said.

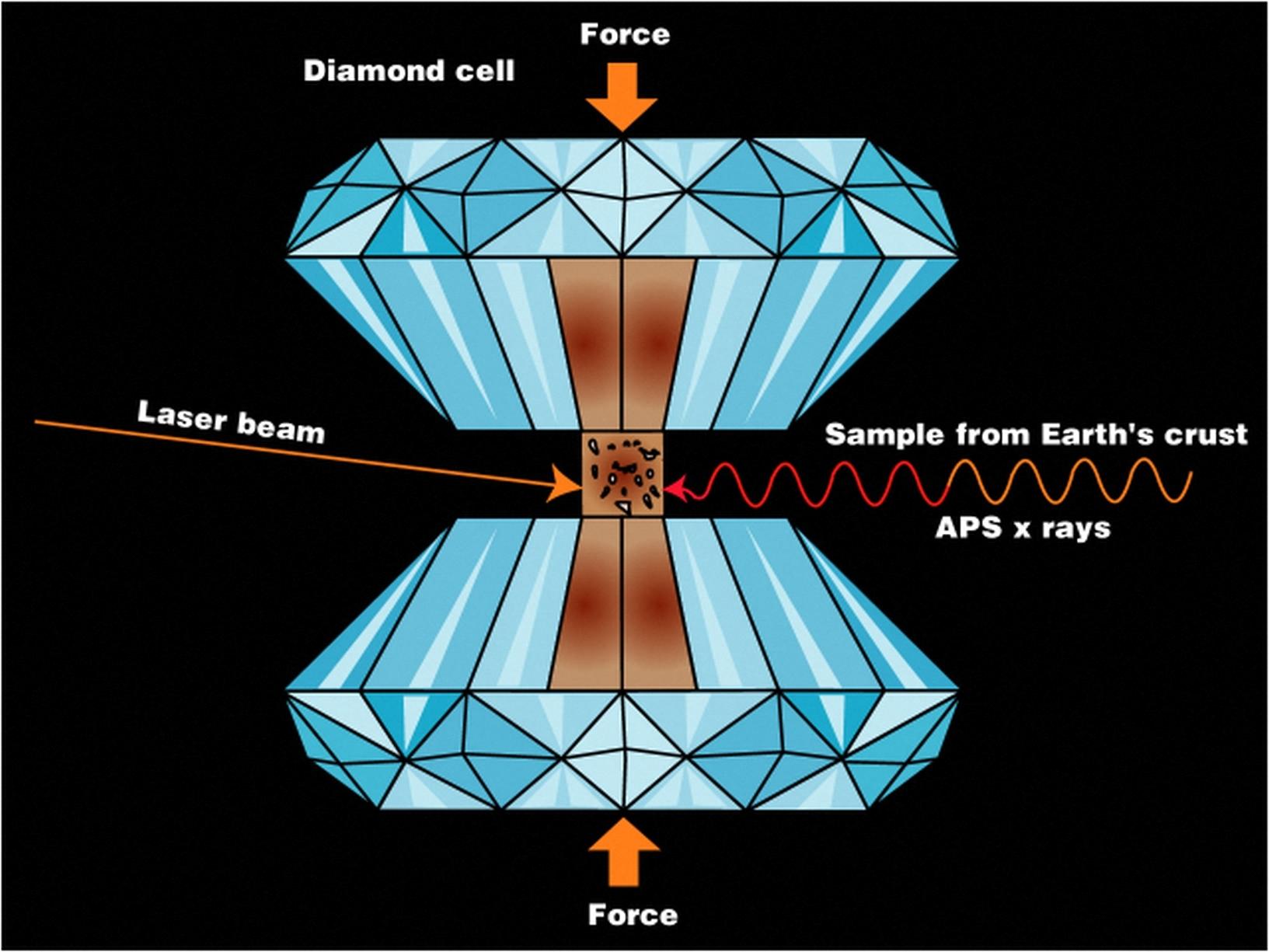

The researchers simulated the conditions that likely existed when Earth's core was forming. To begin, they coated a tiny sample of iron metal with hydrous silicate glass to model the core covered in magma. Then, they placed this object inside a diamond anvil cell — a device in which two diamond crystals squeeze together to generate extreme pressure similar to that found in Earth's core. To create high-temperature conditions, the scientists used lasers that heated the object to about 8,730 degrees Fahrenheit (4,830 degrees Celsius).

The researchers used atom probe tomography in this context. They discovered that hydrogen, oxygen and silicon dissolve into iron crystal structures simultaneously under extreme conditions, thus altering the crystals in previously unknown ways.

Crucially, equal amounts of hydrogen and silicon entered the "core" from the "magma" in the experiment, which helped the researchers estimate that hydrogen makes up 0.07% to 0.36% of Earth's core by weight.

The results, published Tuesday (Feb. 10) in the journal Nature Communications, suggest Earth's core contains nine to 45 times as much hydrogen as the planet's oceans. If comets had delivered hydrogen to Earth after the core had finished forming, hydrogen would mostly occur in Earth's shallower layers. But the finding that the core is Earth's biggest hydrogen reservoir indicates that hydrogen was delivered before the core was fully formed, Huang said.

"This is the first time that the mechanism of how hydrogen enters the core was identified," he said.

Huang, D., Murakami, M., Gerstl, S. & Liebske, C. (2026). Experimental quantification of hydrogen content in the Earth's core. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-68821-6

What's inside Earth quiz: Test your knowledge of our planet's hidden layers

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus