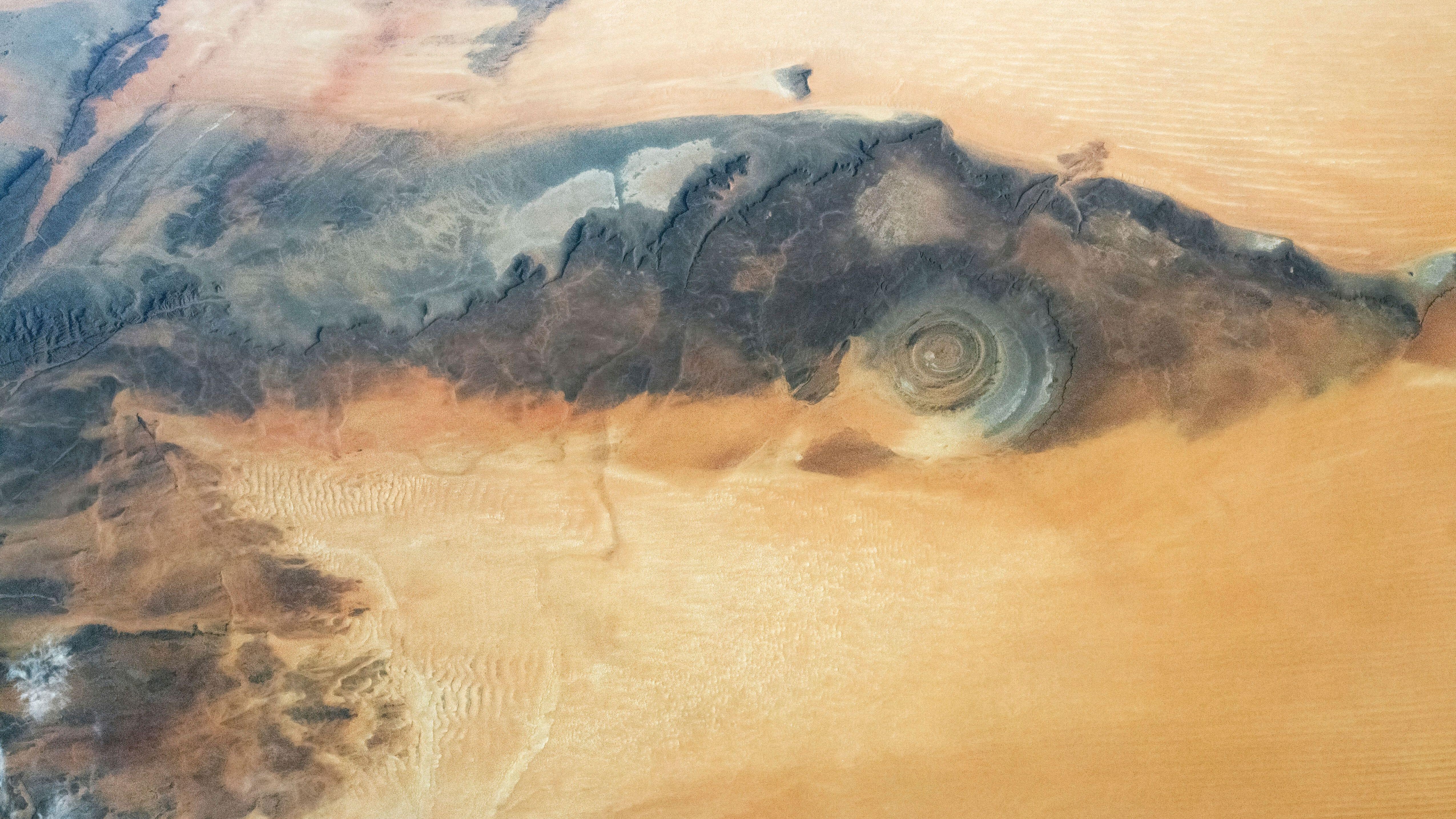

Eye of the Sahara: Mauritania's giant rock dome that towers over the desert

The Eye of the Sahara, also known as the Richat structure, stands out like an oversized ammonite among the sand dunes of the Sahara desert in Mauritania.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Name: Eye of the Sahara

Location: Adrar Plateau, Mauritania

Coordinates: 21.114714464479544, -11.394300583868517

Why it's incredible: The eye is so big you can see it from space.

The "Eye of the Sahara" — also known as the "Eye of Africa" or the Richat structure — is a giant rock dome, carved with concentric rings, that looks like a giant bullseye when seen from above. The eye is visible from space and has been known to astronauts and scientists since the earliest crewed missions in the 1950s, according to the European Space Agency (ESA).

Estimates of the Eye of the Sahara's dimensions range from 25 to 31 miles (40 to 50 kilometers) in diameter. The eye forms a near-perfect circle in the desert of Mauritania, which initially led scientists to think it was an impact structure from a meteor. However, subsequent research found the dome was shaped by tectonic uplift during the Cretaceous period (between 145 and 66 million years ago) and laid bare through erosion.

The Eye of the Sahara stands out like an oversized ammonite among an immense sea of sand known as the Erg Oudane, which stretches roughly 350 miles (560 km) east to Mali. Ergs are areas of desert that span at least 48 square miles (125 square kilometers) and feature wind-swept sands with little to no vegetation. The eye towers about 660 feet (200 meters) above the surrounding sands, which rise against its southern edge and occasionally obscure parts of the structure in photographs, according to ESA.

The center of the Eye of the Sahara is a round plateau of limestone and breccias — sedimentary rocks with large, broken fragments that are cemented together by a fine-grained matrix — according to a 2021 study. The rest of the eye slopes down from this plateau in a circular pattern of ridges and grooves that have been sculpted by wind and water over the eons. The ridges are mostly made of resistant quartzite, while the grooves consist of less-resistant sedimentary rocks that wear away more quickly.

The reason why the eye is so round remains unclear, according to the Lunar and Planetary Institute. Erosion has exposed four types of igneous rock — gabbros, rhyolites, carbonatites and kimberlites — which are younger than the center of the eye, indicating that jets of molten rock rose and solidified at the surface. Several faults are also visible on the outer rings of the eye, suggesting that layers of rock shifted apart in the process.

The Eye of the Sahara is a geological marvel, but it also holds archaeological significance, according to Geographical, a magazine published by the U.K.'s Royal Geographical Society. Excavations have unveiled 2-million-year-old Acheulean and pre-Acheulean tools that are associated with two species of ancient human ancestors: Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Proponents of the debunked myth of Atlantis — a "lost" island subcontinent idealized by some as an advanced, utopian society — claim the Eye of the Sahara is evidence of the city described by Plato in his "Timaeus" and "Critias" dialogues.

But "together, modern archaeology and geology provide an unambiguous verdict," Ken Feder, a professor emeritus of archaeology at Central Connecticut State University, previously told Live Science. "There was no great civilization called Atlantis."

There's no need to turn to mythology for answers when geology provides enough of its own.

Discover more incredible places, where we highlight the fantastic history and science behind some of the most dramatic landscapes on Earth.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus