Science history: Computer scientist lays out 'Moore's law,' guiding chip design for a half century — Dec. 2, 1964

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Milestone: Moore's law introduced

Date: Dec. 2, 1964

Where: San Francisco Bay Area

Who: Gordon Moore

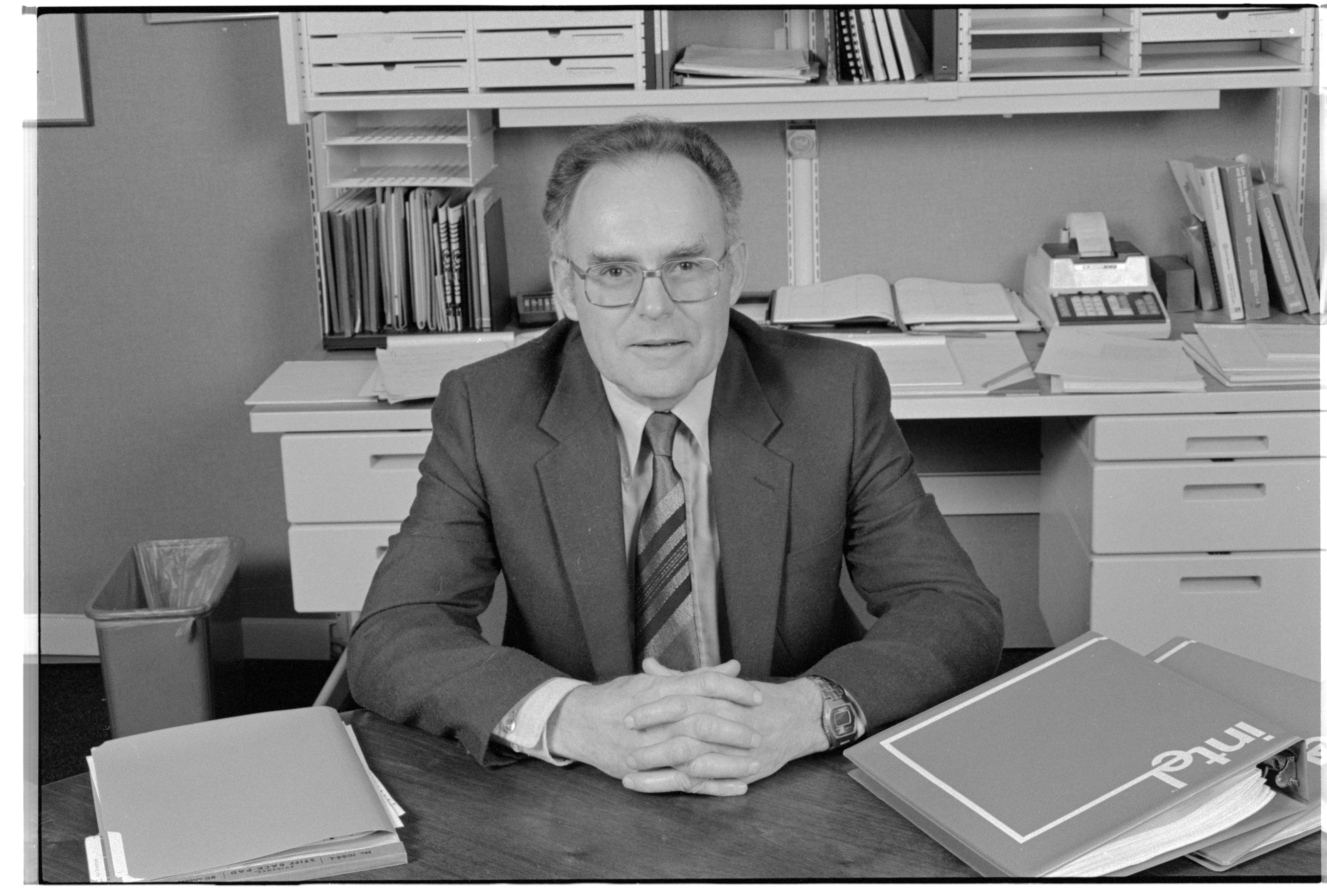

At a low-key talk for a local professional society in 1964, computer scientist and chemist Gordon Moore laid out a prediction that would define the world of technology for more than 50 years.

In the presentation for The Electrochemical Society, titled, "The Evolving Technology of the Semiconductor Integrated Circuits," Moore predicted that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit would double every year.

The final version of this prediction would become known as "Moore's law," and it would drive progress in the semiconductor industry for decades.

Although it's called a law, it was a prediction based more on economic dictates and industry trends than on the physical laws of nature.

Moore was a director of research and development at Fairchild Semiconductors when he gave the talk, and his goal was ultimately to sell more chips. At the time, computers were gigantic machines that took up a whole room, and integrated circuits, known as microchips, had somewhat limited practical applications.

The silicon transistor, the workhorse that does calculations in a computer, had been invented just a decade earlier, and the integrated circuit, which allowed computers to be miniaturized, had been patented just five years earlier. In 1961, the electronics company RCA had built a 16-transistor chip, and by 1964, General Microelectronics had built a 120-transistor chip.

Moore witnessed this dramatic progress and noticed that a mathematical rule seemed to be governing that progress. This mathematical correlation was later given the name "Moore's law" by other people.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Although Moore laid out the principle to The Electrochemical Society in 1964, it gained widespread traction in April of the following year, when he was asked to write an editorial in Electronics magazine. In it, he boldly predicted that as many as 65,000 components could be squeezed onto a single chip — an unheard-of number at the time. It's a charmingly small-potatoes number now, given that in 2024, a company unveiled a 4 trillion-transistor chip.

In 1968, Moore would co-found the chipmaker Intel, where his doubling law would go from a casual observation to a motivation for innovation.

Despite its name, Moore's law was never an ironclad rule. In 1975, Moore downgraded the pace of progress to transistor doubling every two years, rather than every year. That more modest doubling rate would become the official Moore's law, which would hold for years after. This relentless drive toward more computing power and miniaturization is what enables virtually all modern electronics, from the personal computer to the smartphone.

For years, people predicted that the law would become outdated, but it proved remarkably resilient for quite some time.

"The fact that we've been able to continue [Moore's law] this long has surprised me more than anything," Moore said in an interview with The Electrochemical Society in 2016. "There always seems to be an impenetrable barrier down the road, but as we get closer to it, people come up with solutions."

However, eventually, the principle would no longer hold. It's not clear exactly when Moore's law became defunct. In its canonical form, the standard likely died in 2016, as it took Intel five years to go from the 14-nanometer-size technology to 10 nanometers. Moore saw this happen, as this was years before he died at the ripe old age of 94 in 2023.

Eventually, Moore's "law" had to peter out because it runs up against the actual laws of physics. As transistors became ever smaller, quantum mechanics, the physics that governs the very small, began to play an outsize role. The world's smallest transistors can face problems with "quantum tunneling," wherein electrons in one tiny transistor can tunnel into another, thereby allowing current to flow in transistors that should be in the "off" position.

As a result, chipmakers are looking at designing chips with new materials and new architecture. The next Moore's law may apply to quantum computers, which harness quantum mechanics as a feature, not a bug, of calculations.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus