Science history: 'Father of modern genetics' describes his experiments with pea plants — and proves that heredity is transmitted in discrete units — Feb. 8, 1865

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Milestone: Principles of inheritance discovered

Date: Feb. 8 and March 8, 1865

Where: Brno, in what is now the Czech Republic

Who: Gregor Mendel

On a cold day in February, an Augustinian friar described his experiments breeding garden-variety plants — and gave rise to the field of modern genetics.

Gregor Mendel was an Austrian priest who had spent eight years cultivating and crossbreeding more than 28,000 pea plants (Pisum sativum) in the garden of Monastery of St. Thomas in Brno (formerly known as Brünn), painstakingly recording details of the plants' progeny.

Mendel was actively discouraged from pursuing his research. His bishop giggled whenever Mendel told of his scientific experiments, according to a letter his abbot Cyril Napp wrote to him in 1859.

"He asked if I though [sic] it seemly for a man of your intellectual attainments to be plodding in a pea patch, prying into the germinal proclivities of peas. He suggested that pea propagation was a subject less worthy of your curiosity than, say, the writings of the Church Fathers or the Doctrine of Grace. My dear Brother Mendel, as sympathetic as I am to your researches [sic], we can ill afford to have the monastery made the laughingstock of the diocese."

But Mendel was undeterred from his research — not because of a deep-seated interest in plants, but because he wanted to reveal the principles of inheritance.

He had chosen to study the plants of this unassuming legume for a number of reasons. First, pea plants reproduced quickly and well in both pots and in the ground, according to an 1866 monograph he wrote about his research. Second, they seemed to have clear traits they passed along to their offspring — such as pink, white or red flowers — and the hybrids were perfectly fertile.

Finally, "accidental impregnation by foreign pollen, if it occurred during the experiments and were not recognized, would lead to entirely erroneous conclusions," he wrote.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

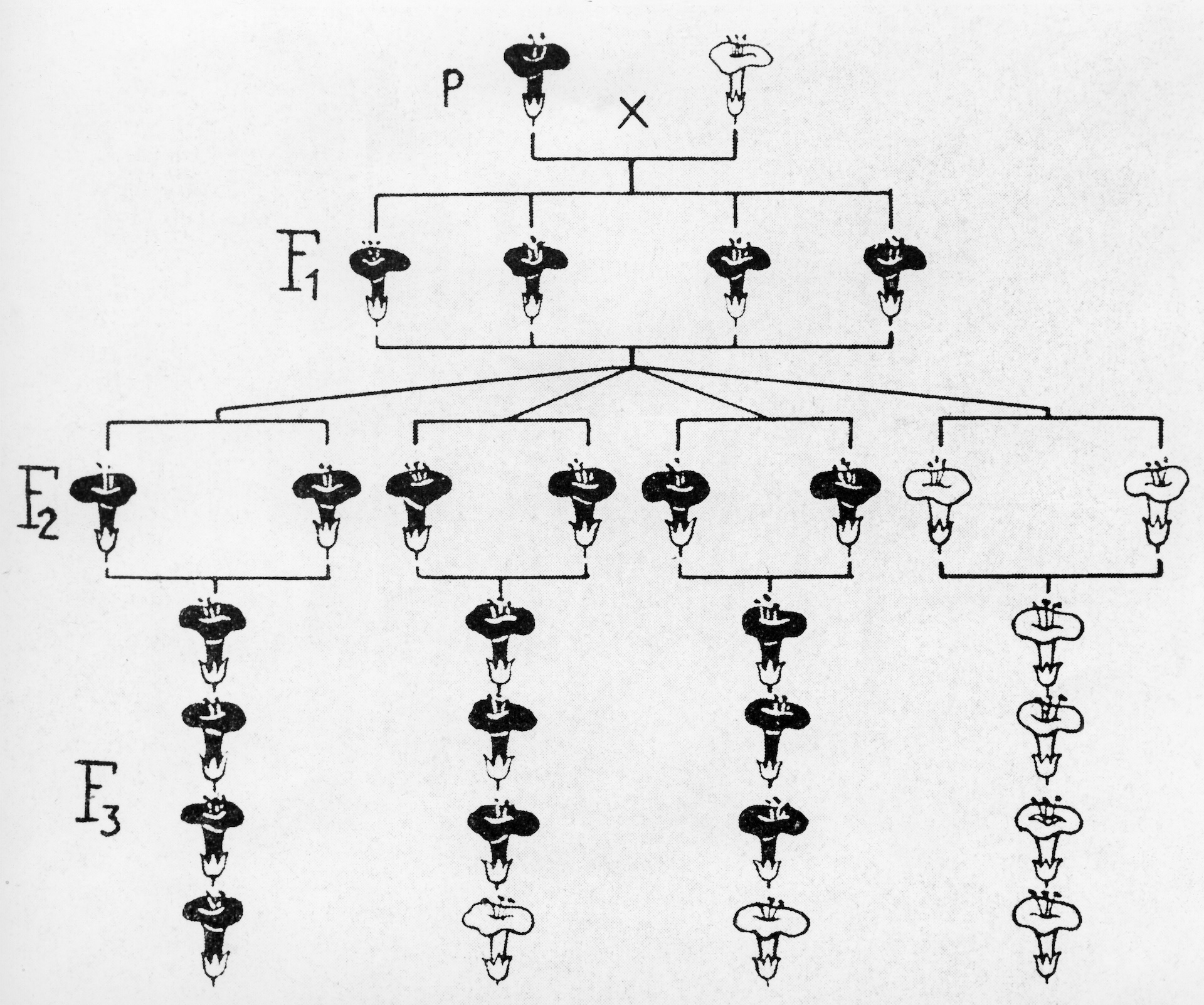

He identified several distinct traits to track — such as the color of the peas and their pods, the positions of the flowers, and the lengths of the stems — and then crossbred those with differing characteristics. Then, he let each distinct type of plant "self-breed" for two years, showing that the traits continued to be passed along to offspring.

Next, he crossbred those plants and crossbred the resulting hybrids. He painstakingly tallied all of the ways traits were inherited, denoting different traits from each parent with simple labels like Aa, Bb and Cc.

By analyzing the mathematical patterns in each subsequent generation, he deduced the basic principles of inheritance. First, he noted that some traits were transmitted in discrete units, or "particles" — if you cross a green-pea plant with a yellow-pea plant, you get either green or yellow offspring, not yellowish-green ones.

He also concluded that some traits were inherited in a "dominant" pattern. For instance, if plants bred for generations to have only smooth seeds were bred with those that had wrinkly seeds, the offspring would always have smooth seeds.

When Mendel crossbred hybrids, he noticed something strange: Most of the plants would look smooth, but about a quarter would look wrinkled. He deduced that the wrinkly trait was instead passed on in a "recessive" manner and that the trait actually came from the grandfather plant's generation.

Mendel wasn't content to study one "particle" at a time. He also crossbred plants that were hybrids for two different traits and learned that each trait was transmitted separately, which is now known as the principle of segregation.

Mendel's work wasn't recognized in his lifetime. And although Mendel is often known as the "father of genetics," the term "genetics" was not coined until the early 1900s, when English biologist William Bateson rediscovered Mendel's forgotten work and realized its overarching significance.

Soon after, some argued Mendel's data was "too good to be true," and that he must have fabricated his results. A 2020 study put that idea to rest, showing that given the seeds available then, what Mendel knew, and how seeds were classified then, his results were in fact what you'd expect.

Decades later, research would reveal that inheritance isn't as simple as Mendel's pea plants would suggest — some genes are inherited in a sex-linked manner, and other traits have incomplete "penetrance," meaning they don't always manifest the same way. And in early 2026 research revealed that some disease-causing genes we believed were dominant don't operate like we thought, which may challenge some of the fundamental tenets of Mendelian inheritance.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus