High-fiber diet may 'rejuvenate' immune cells that fight cancer, study finds

A laboratory study reveals an interaction between dietary fiber and the gut microbiome that may be helpful for fighting cancer.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Microbes in the gut can help the immune system fight cancer, and a fiber-rich diet may be the key to unlocking those benefits, a study in mice suggests.

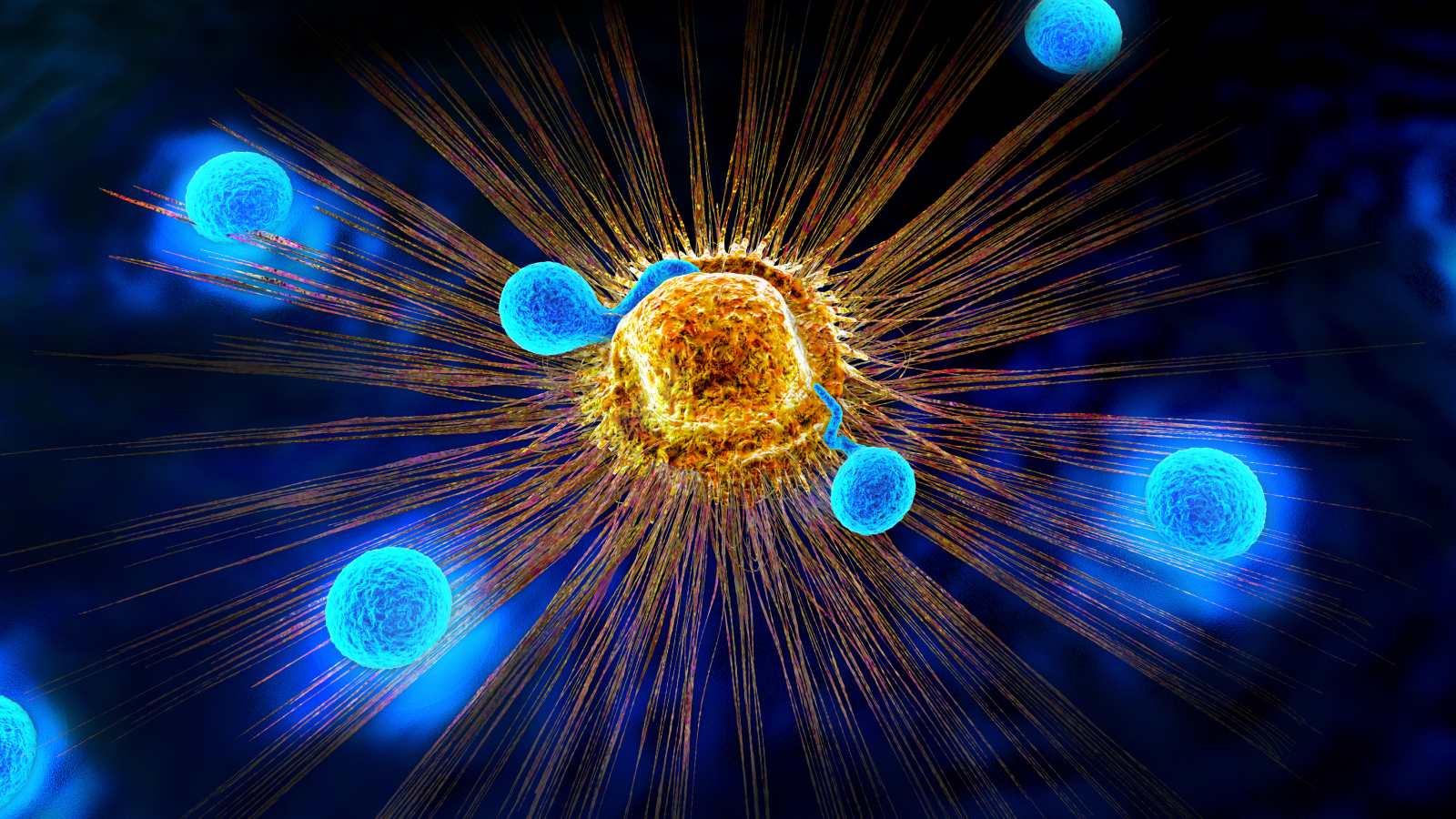

The immune system is a key player in the body's battle against cancer. On the front line of this resistance are CD8+ killer T cells, a type of immune cell that marauds around tumors and then exterminates the cancerous cells. But after each successive battle, these cells become worn out and don't find tumors as effectively. As such, treatments that provide the cells with enough pep to finish their job are in high demand.

Now, in a study published Nov. 11 in the journal Immunity, researchers report that simple dietary changes may help revive these key immune cells by affecting the gut microbiome — the collection of microbial species in the gastrointestinal tract.

The team, led by Dr. Sammy Bedoui, an immunologist at the University of Melbourne in Australia, didn't set out to study cancer at all. Instead, their project began nearly a decade ago with "blue-sky discovery research," without a particular outcome in mind, he told Live Science.

The team was broadly exploring how CD8+ T cells defend the body. Some of their research involved mice that were genetically modified to lack gut microbiomes, and the team noticed that T cells transferred into these rodents started to die out after a couple of weeks. They began to look for a factor released by the microbiome that could help T cells thrive.

In a 2019 paper, they found that factor. When a lot of dietary fiber reaches the gut, bacteria in the colon cause the fiber to ferment. This process releases different chemicals, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Bedoui, alongside study co-author and senior research fellow Annabell Bachem, showed that a particular SCFA — butyrate — rejuvenated tired-out T cells.

"They look very much like those cells that we would like to have when we treat patients or mice with immunotherapies," Bedoui said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Having initially shown this effect in healthy microbiota-free mice, the researchers built on this idea in their new study. They tested whether butyrate could amp up T cells in mice with the skin cancer melanoma. They put half of these mice on a high-fiber diet, which, in turn, ramped up SCFA production by their gut microbes. The mice remained tumor-free longer than mice fed a low-fiber diet, and they had smaller tumors overall; in short, the high-fiber group had slower cancer progression.

In another experiment, the team bred mice that lacked T cells and subjected them to the same protocol. Among these mice, the high-fiber diet didn't come with improved cancer outcomes, suggesting that something specific about the fiber's effect on T cells was what slowed disease progression.

The team explored how the SCFAs might be altering the mice's T cells. In the mice fed more dietary fiber, the team found more T cells specialized to fight melanoma. Specifically, these cells were seen in the tumor-draining lymph node, a staging post where T cells amass before tackling a tumor.

Importantly, these cells carried a protein that pointed to cancer-fighting prowess. "They can stay around in the body for a really long time," Bachem said of the cells. "They have the potential to get activated well, and then to differentiate into different subsets."

The team's findings differed from previous studies in that it didn't focus on the medical value of particular bacterial species, Bedoui said. No lone bug in the team's analysis contributed to the impact; it was a group effort.

"It's not so much who is there in terms of bacteria but what they are doing," Bedoui said.

These findings have opened a rich vein of future research. Bedoui and Bachem will now explore in clinical studies whether additional dietary fiber might help human melanoma patients and whether butyrate might also give other T cells their mojo back.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical or dietary advice.

RJ Mackenzie is an award-nominated science and health journalist. He has degrees in neuroscience from the University of Edinburgh and the University of Cambridge. He became a writer after deciding that the best way of contributing to science would be from behind a keyboard rather than a lab bench. He has reported on everything from brain-interface technology to shape-shifting materials science, and from the rise of predatory conferencing to the importance of newborn-screening programs. He is a former staff writer of Technology Networks.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus