Scientists invent tool to see how 'healthy' your gut microbiome is — does it work?

A new tool can reveal whether someone has a "healthy" gut microbiome by providing a simple score, but many questions remain.

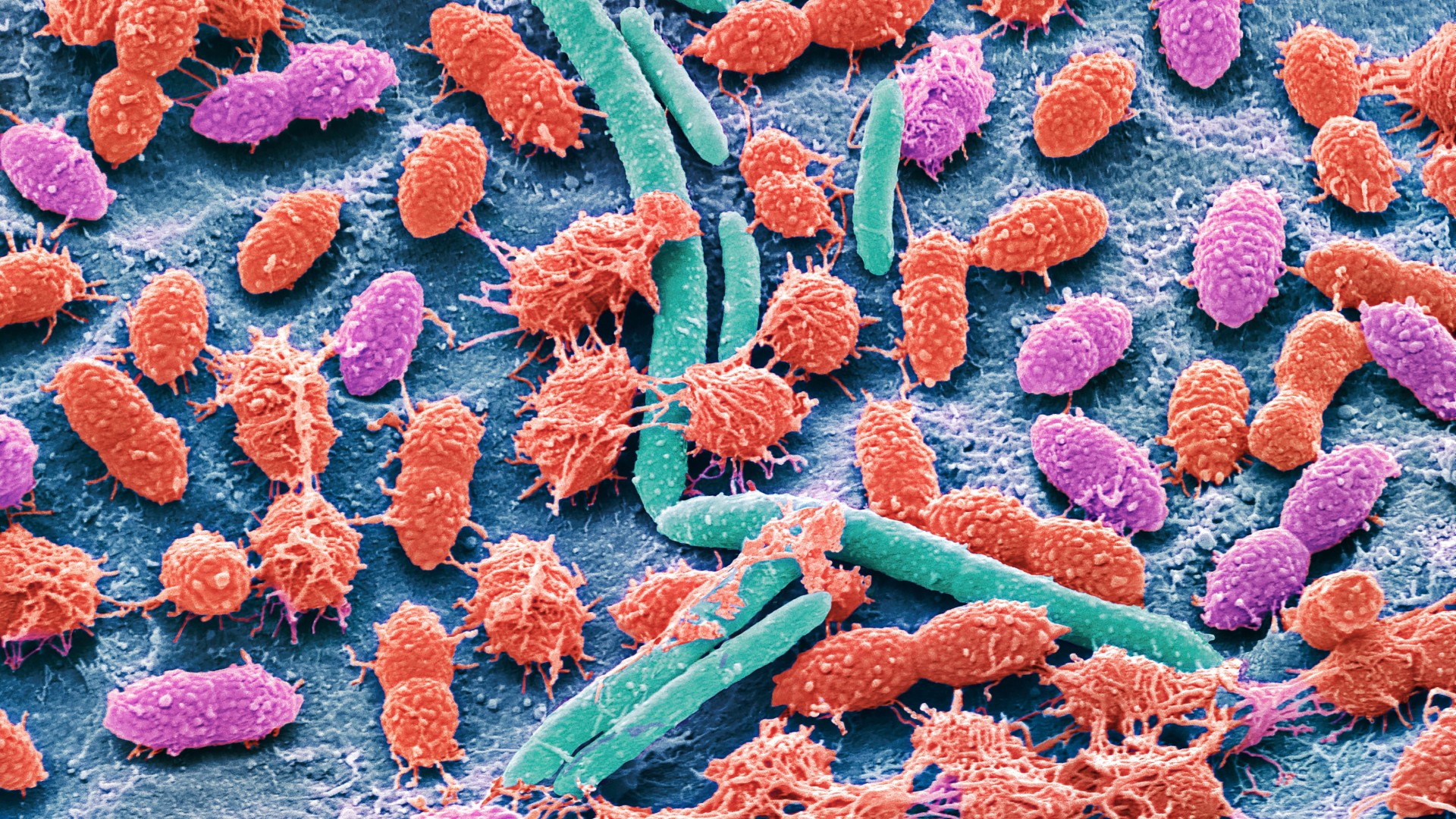

The gut microbiome, the community of microorganisms that live in the colon, may shape a person's risk of developing chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes and heart disease. Now, scientists have developed a computational tool that they say can reveal how "healthy" a person's gut microbiome is, using data from a single stool sample.

Although the concept is intriguing, experts told Live Science they have reservations about how useful the new tool would actually be to patients.

The tool, called the Gut Microbiome Wellness Index 2 (GMWI2), gives users a score between -6 and +6. The higher the score, the "healthier" their gut microbiome reportedly is, and vice versa. In a recent study, published Aug. 28 in the journal Nature Communications, researchers found that the GMWI2 was 80% accurate at differentiating between a "healthy" gut microbiome, on the positive end of the spectrum, and an "unhealthy" one, on the opposite end. The tool was trained on stool samples from 8,000 people and then tested on samples from 1,140 people.

Anyone can freely download and use GMWI2, but they'll need a "basic computer science or bioinformatics background" to interpret the results, study co-author Jaeyun Sung, an assistant professor of surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, told Live Science.

Related: The gut microbiome has a circadian rhythm. Here's how it might affect your health.

The team hopes that eventually, anyone will be able to get a gut health score from their local clinic by providing a stool sample, Sung said. However, other experts have expressed concerns about the potential utility of such a tool. They wonder what it means to have a "healthy" gut microbiome in this context and who might stand to benefit from learning their gut health score.

Defining "healthy"

GMWI2 is built upon a type of machine learning, an artificial intelligence (AI) tool that can make predictions about a piece of data based on a set of rules it has been trained to follow. Typically, scientists "train" the AI by providing troves of data from a given population, and then once it has picked up common patterns in that data, the tool can make predictions about new data from a different group of people.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In this case, the researchers trained GMWI2 to identify specific features of the gut microbiomes of people who have a disease — say, diabetes — and compare them to the gut microbiomes of people without that condition. They did this by feeding it data on the mix of microbes found in the stool samples from about 8,000 people from 26 countries on six continents.

Around 5,500 of those individuals had been previously diagnosed with one of 11 diseases, including colorectal cancer and the inflammatory bowel disease Crohn's disease. The remaining 2,500 people didn't have a diagnosis of any of the 11 conditions. After training the tool with these data, the researchers tested how well it worked on another 1,140 stool samples from patients who were either diagnosed with diseases, such as pancreatic cancer and Parkinson's disease, or not.

The researchers found that the higher a person's GMWI2 score is, the more closely their gut microbiome resembles that of someone who does not have one of these diseases. A lower score suggests the opposite — that their gut microbiome looks distinct from that of an individual with any of these conditions.

Unlike well-established diagnostic tools, such as colonoscopies for colorectal cancer, GMWI2 is not designed to diagnose specific diseases, the study authors emphasized. Rather, it's meant to flag subtle changes in a person's gut health that may hint that they're likely to develop a given disease, they wrote.

Instead of providing diagnoses, Sung said, the tool could potentially be used by people who are otherwise healthy but who want to optimize their gut health to prevent disease, he said. It may also be helpful to those who are more likely to develop a particular disease because it runs in their family, he suggested.

GMWI2 could also be used to assess how well someone's gut is recovering after they've been given chemotherapy or antibiotics, as both of these treatments can harm the microbiome, he added. These treatment-induced changes can weaken the immune system, making patients more vulnerable to future infections.

Related: Scientists unveil 'atlas' of the gut microbiome

No "one-size-fits-all" solution

Despite the potential appeal of a tool like GMWI2, experts told Live Science that they have some reservations about how it could be used in real life.

The study is a "heroic attempt" to tie specific gut microbiome signatures to either health or disease, said Willem De Vos, an emeritus professor of human microbiomics at the University of Helsinki who was not involved in the research. However, "one of the problems with the approach is that health is hard to define — health is more than the absence of disease," de Vos told Live Science in an email.

Some scientists argue that there is no universally accepted definition of health, because health is a relative condition. Health for one person doesn't necessarily mean the same thing as it does for another — for example, two people may get a GMWI2 score of +6, but the composition of their microbiome may completely differ. This can make it hard to define what a "healthy microbiome" is.

A person's health also changes throughout their lifetime, so any health scores that are garnered from a tool like GMWI2 would become "meaningless" unless they are repeated over time, said Dr. Fergus Shanahan, a professor and chair of the Department of Medicine at University College Cork in Ireland, who was not involved in the research but is an expert in the gut microbiome. The abundance of certain microbes in the gut also fluctuates daily, and can be influenced by a person's diet, stress levels or mood.

This means that a person who is trying to monitor the health of their gut microbiome after a round of antibiotics, for instance, would need to keep using the tool on a regular basis, such as every week or month, Sung said.

Furthermore, several versions of GMWI2 may need to be developed in order to tailor the tool to different populations, Shanahan told Live Science in an email. "Several studies have shown that the composition of the microbiome varies considerably in different ethnic groups, sometimes quite markedly," he said. This may be caused by varying social and environmental factors, including diet and lifestyle.

"Thus, any tool for measuring health of an individual must be adapted to the population within which the individual lives," Shanahan argued.

It's also currently unclear what people would do to alter a "suboptimal" GMWI2 score. In the paper, Sung and colleagues mention that it might prompt people to get more diagnostic tests or to modify certain aspects of their diet or lifestyle. However, without knowing what disease a patient has — if any — it may be difficult to implement any targeted interventions.

The team is now developing the next version of the tool, which will be known as the Gut Microbiome Wellness Index 3. (GMWI2 was an update to the more basic prototype, the Gut Microbiome Wellness Index, which was introduced in 2020 and trained on a much smaller number of stool samples.)

They aim to train the next iteration of the tool using at least 12,000 stool samples from a much more diverse cohort of people. They also plan to use more sophisticated machine learning algorithms to interpret the data, Sung said. Assuming they earn regulatory approval, it's possible that the tool could be put on the market within the next two years or so, he predicted.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus