Here's Why Antibiotics May Give Viruses a Leg Up

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Why are infections from the viruses that cause West Nile fever, dengue and even Zika deadly for some people but mild in others?

The answer thus far has been chalked up to being mostly a matter of human genetics. But a major factor in whether these viruses wreck your health may come down to the profile of bacteria that inhabit your intestines, called the gut microbiome, a new study in mice suggests.

The study, published today (March 27) in the journal Cell Reports, found that these particular viral infections were more likely to be deadly if the infected mice had been treated in advance with antibiotics. (More research is needed to confirm the findings in humans, whose microbiomes differ from those of mice.) [9 Deadliest Viruses on Earth]

The reason is that antibiotics wipe out the gut microbiome, and this weakened microbiome somehow"impairs your immune system," senior study author Dr. Michael Diamond, a professor of medicine, molecular microbiology, pathology and infectious disease at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

"The immune system is activated differently if the gut does not have a healthy microbiome," Diamond said in a statement. "If someone is sick with a bacterial infection, they absolutely should take antibiotics. But it is important to remember that there may be collateral effects. You might be affecting your immune response to certain viral infections."

Antibiotics kill bacteria, not viruses. Nevertheless, some doctors prescribe antibiotics for viral infections such as colds and the flu as an extra precaution, perhaps to ease the concerns of patients who think they need medicine, or to prevent a subsequent bacterial infection from arising while the body is weak. But that practice — giving antibiotics as a preventive measure— may backfire.

"Taking antibiotics [by chance] could affect [the] responses" of the immune system to a variety of viruses, Diamond told Live Science. "That would be an implication of our study, but, of course, [this] requires further validation — especially in humans."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Gut bugs and viruses

Scientists have uncovered many beneficial roles of the gut microbiome. Microbes in the small intestine help digest food, synthesize vitamins and regulate metabolism. What's more, the dominance of "good" bacteria helps to prevent the establishment of harmful bacteria, such as Clostridium difficile (C. diff.), which can cause a difficult-to-treat infection that can be life-threatening.

Only in recent years, however, have scientists homed in on the direct connection between the gut microbiome and the immune system. The presence of healthy bacteria seems to improve the body's ability to produce T cells, a type of white blood cell that attacks and destroys viruses and other disease-causing microbes, Diamond said.

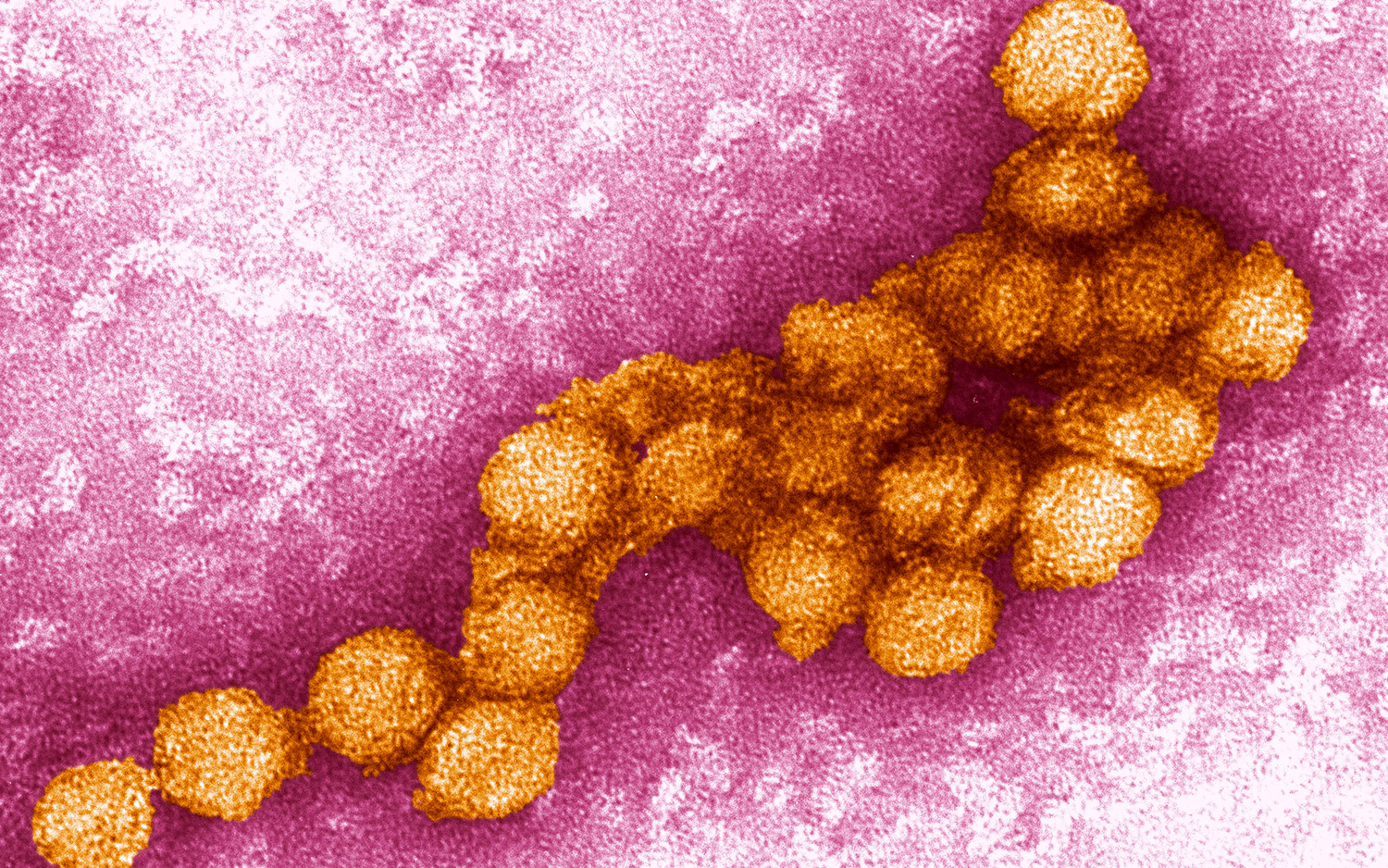

In the new study, the researchers infected mice with the Zika, West Nile and dengue viruses, all of which are part of a group of viruses called flaviviruses. All three viruses were more harmful to the mice who had received antibiotics prior to infection than to the mice that didn't receive antibiotics, the researchers found.

The researchers then examined West Nile virus in greater detail. This virus is typically spread by mosquitoes and can cause swelling in the brain. The researchers gave mice either a placebo or a cocktail of four antibiotics — vancomycin, neomycin, ampicillin and metronidazole — for two weeks before infecting them with the virus. About 80 percent of the mice that received no antibiotics survived the infection, while only 20 percent of the antibiotic-treated mice did. [5 Things You Need to Know About West Nile Virus]

Different antibiotic treatments administered separately or in combinations led to different changes in the bacterial community in the mouse gut, and these changes correlated with vulnerability to the viral infection in the study. For example, treatment with ampicillin or vancomycin alone made the mice more likely to die from West Nile infection. Metronidazole had no effect alone, but it amplified the effect of ampicillin or vancomycin.

"Once you put a dent in a microbial community, unexpected things happen," lead study author Larissa Thackray, an assistant professor of medicine also at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, said in a statement. "Some groups of bacteria are depleted, and different species grow out. It's likely that antibiotic use could increase susceptibility to any virus that is controlled by T-cell immunity, and that's many of them."

Independent research on rodents has found that a healthy microbiome may also help control influenza virus and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, a type of virus that infects rodents and is similar to the virus that causes Lassa hemorrhagic fever and similar diseases in humans.

The big question, the researchers said, is to what degree the microbiome outweighs other factors in disease progression, such as age, genetics, prior viral exposures and other diseases a person might have. In other words, does a person's microbiome play a larger role than these other factors in how bad a viral infection will be? More research is needed, particularly in humans.

Still, the findings suggest that for humans, taking antibiotics unnecessarily may be unwise because of the potential effects on immune responses, Diamond said.

Follow Christopher Wanjek @wanjek for daily tweets on health and science with a humorous edge. Wanjek is the author of "Food at Work" and "Bad Medicine." His column, Bad Medicine, appears regularly on Live Science.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus