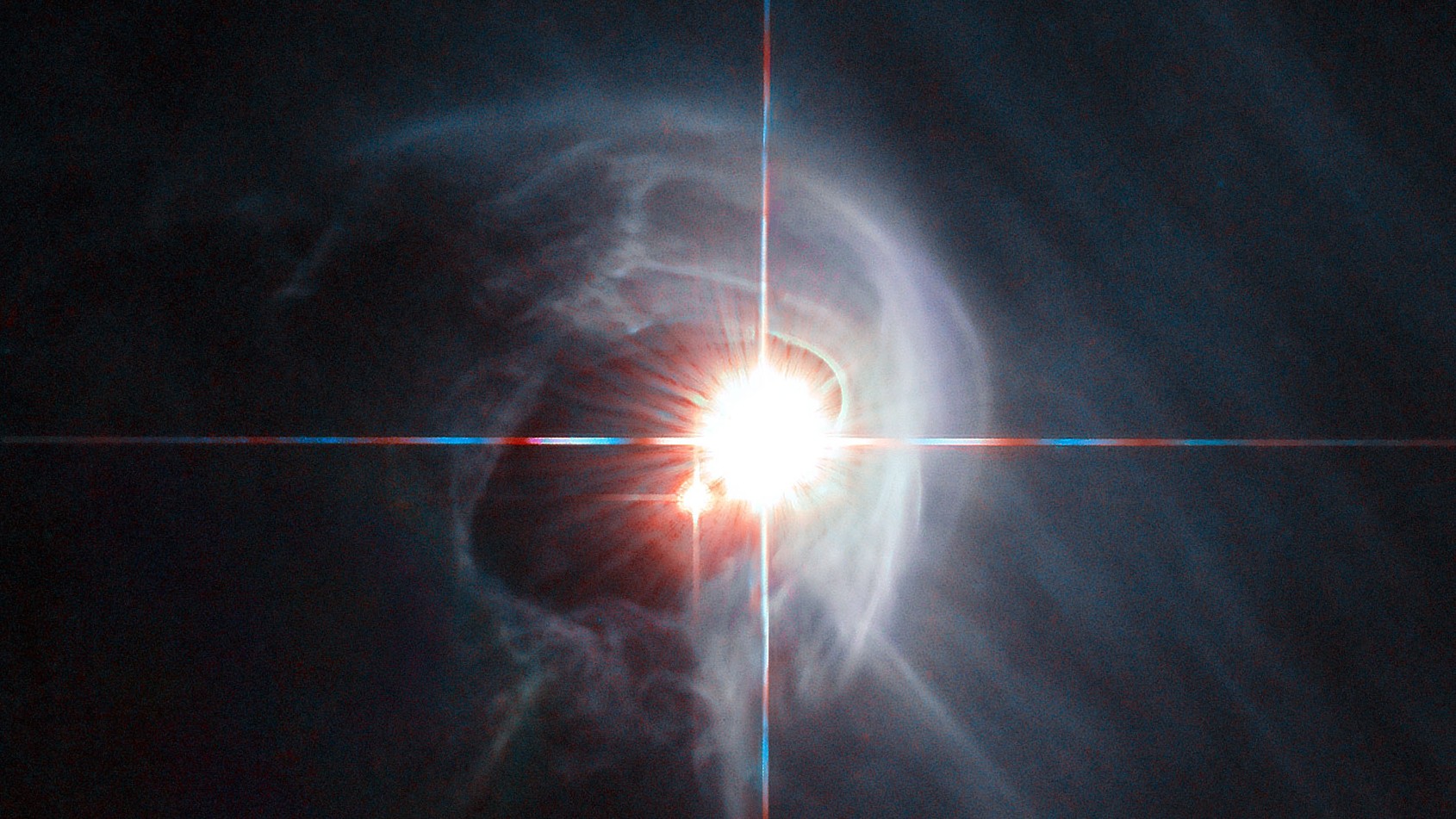

Two stars spiraling toward catastrophe are putting Einstein's gravity to the test

The two stars in the nearby system ZTF J2130 are spiraling toward a catastrophic supernova. In the meantime, scientists are using the pair's slow orbital decay to put Einstein's theory of gravity to the test.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Astronomers have observed a pair of stars locked in a death spiral, and their dance of doom is revealing more about how gravity works.

The system, called ZTF J2130, sits about 4,000 light-years away. Although astronomers have known about this system for a while, this is the first time they have observed it with such high clarity.

The two stars that make up the system will merge soon. Their spiraling motion agrees with theoretical predictions, which means even more refined future observations will allow researchers to use this system to test our understanding of gravity, the team wrote in a study submitted for publication in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics in October.

This is a very old system. One of the stars is a white dwarf, the white-hot leftover core of a sunlike star. The other is what's known as a subdwarf star, which is a small star near the end of its life cycle. The two stars are so close together that they complete an orbit in just under 40 minutes. In fact, they've already started to kiss. Their mutual gravity is so strong that they've stretched and distorted, with the subdwarf's material flowing onto the white dwarf companion.

Because the stars are pretty hefty and moving very quickly, they emit gravitational waves, which are ripples in the fabric of space-time first predicted by Albert Einstein and confirmed to exist in 2015. This emission of gravitational waves saps energy from the system, inching the two stars ever closer every year.

Using a combination of data from the Oskar Luhning telescope at the Hamburg Observatory in Germany and the CAHA Observatory in Spain in Germany and Spain, the astronomers undertook a painstaking campaign to measure the orbital period as precisely as possible. They found that the orbit is slowly decaying; with every passing second, the orbital period shrinks by about two-trillionths of a second.

This is in line with calculations based on our current theoretical understanding of gravity. But scientists have been eager to move past Einstein's theory of general relativity for more than a century, so any opportunity to test it immediately draws interest.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The astronomers discovered that an upcoming gravitational-wave observatory, known as the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), should be able to directly measure the gravitational waves emanating from this system. The European Space Agency plans to launch LISA in the 2030s, and this stellar pair will still be around next decade.

When the stars finally merge, they will release a supernova-level explosion that might be bright enough to be seen with the naked eye. In the meantime, before we get to enjoy that fireworks show, we'll just have to put gravity to the test.

Paul M. Sutter is a research professor in astrophysics at SUNY Stony Brook University and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. He regularly appears on TV and podcasts, including "Ask a Spaceman." He is the author of two books, "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space," and is a regular contributor to Space.com, Live Science, and more. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus