Physicists capture rare illusion of an object moving at 99.9% the speed of light

For the first time, physicists have simulated what objects moving near the speed of light would look like — an optical illusion called the Terrell-Penrose effect.

Using ultra-fast laser pulses and special cameras, scientists have simulated an optical illusion that appears to defy Einstein's theory of special relativity.

One consequence of special relativity is that fast-moving objects should appear shortened in the direction of motion — a phenomenon known as Lorentz contraction. This effect has been confirmed indirectly in particle accelerator experiments.

But in 1959, mathematician Roger Penrose and physicist James Terrell pointed out that an observer with a camera wouldn't actually see a squashed object at all. Instead, because light from different parts of the object takes different times to reach the camera, it would appear rotated.

Although previous models have worked with this illusion, now called the Terrell-Penrose effect, this is the first time it has been done in a lab setting. The team described their results in the journal Communications Physics.

"What I like most is the simplicity," Dominik Hornof, a quantum physicist at the Vienna University of Technology and first author of the study, told Live Science. "With the right idea, you can recreate relativistic effects in a small lab. It shows that even century-old predictions can be brought to life in a really intuitive way."

Re-creating the illusion

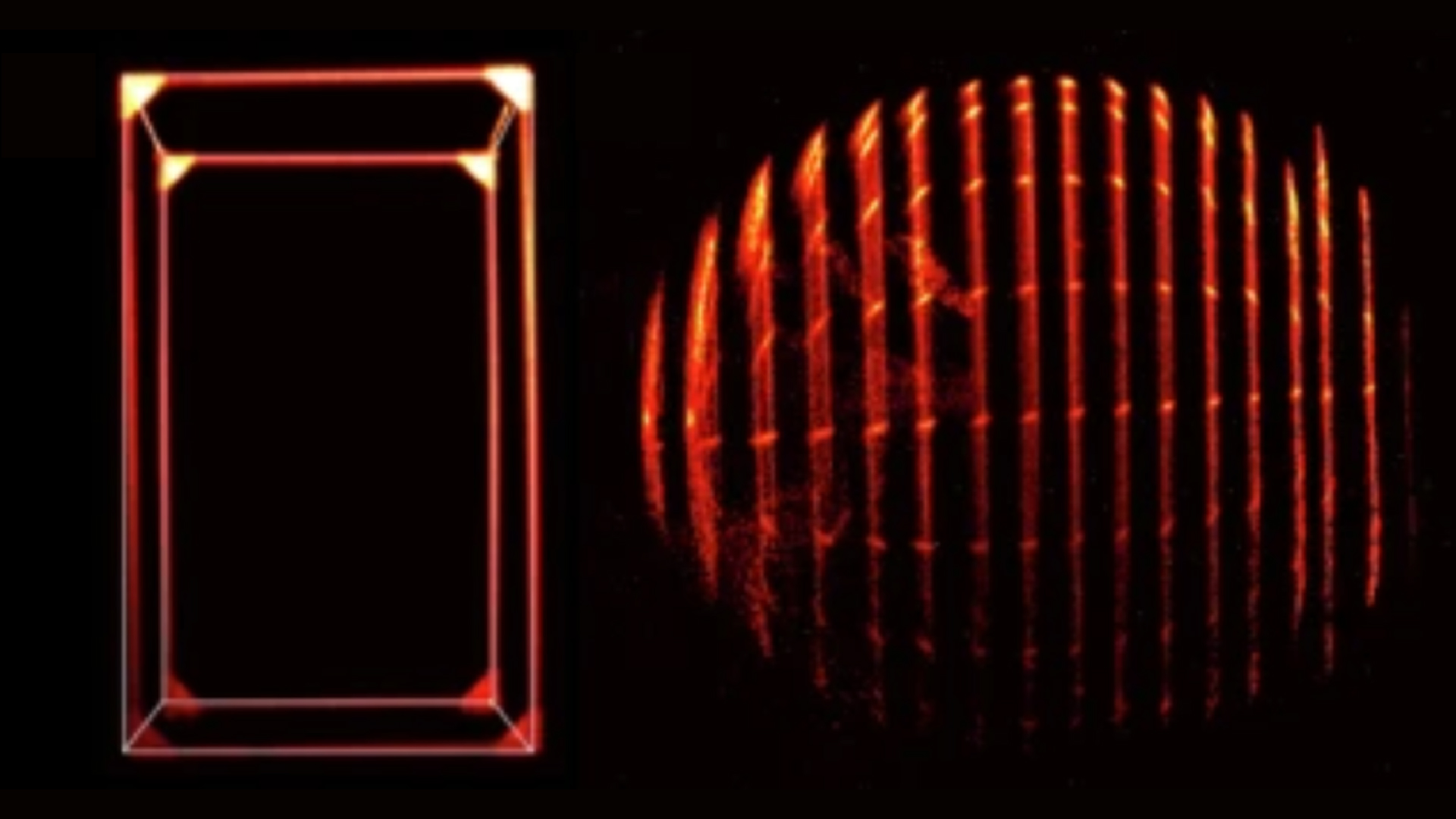

In the new study, physicists used ultra-fast laser pulses and gated cameras to produce snapshots of a cube and a sphere "moving" at nearly the speed of light. The results showed snapshots of rotated objects. This proved the Terrell-Penrose effect to be true.

But like every study, this one also had its difficulties. Moving any object at or near the speed of light is currently impossible. "As you get closer to the speed of light, the energy you need grows by a lot," Hornof said. We cannot generate enough energy to accelerate something like a cube, and "that's why we need huge particle accelerators, even just to move electrons close to that speed. It would take a huge amount of energy."

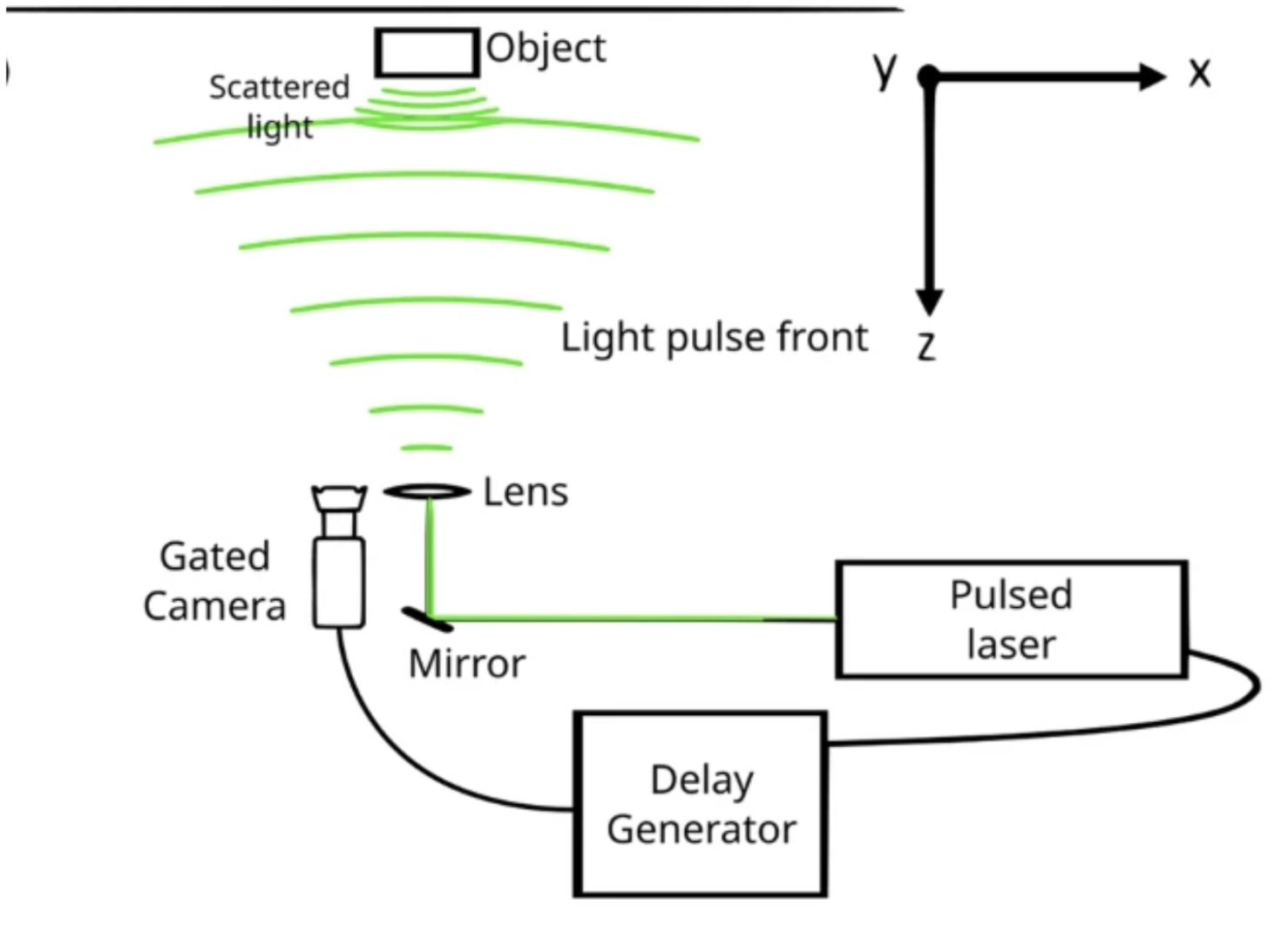

So the team used a clever substitute. "What we can do is mimic the visual effect," Hornof said. They started with a cube of about 3 feet (1 meter) on each side. Then, they fired ultra-short laser pulses — each just 300 picoseconds long, or about a tenth of a billionth of a second — at the object. They captured the reflected light with a gated camera that opened only for that instant and produced a thin "slice" each time.

After each slice, they moved the cube forward about 1.9 inches (4.8 cm). That is the distance it would have traveled if it were moving at 80% the speed of light during the delay between pulses. Then, the scientists put all of these slices together into a snapshot of the cube in motion.

"When you combine all the slices, the object looks like it's racing incredibly fast, even though it never moved at all," Hornof said. "At the end of the day, it's just geometry."

They repeated the process with a sphere, shifting it by 2.4 inches (6 cm) per step to mimic 99.9% light speed. When the slices were combined, the cube appeared rotated and the sphere looked as if you could peek around its sides.

"The rotation is not physical," Hornof said. "It's an optical illusion. The geometry of how light arrives at the same time tricks our eyes."

That is why the Terrell-Penrose effect does not contradict Einstein's special relativity. A fast-moving object is physically shortened along its direction of travel, but a camera doesn't capture that directly. Because light from the back takes longer to arrive than light from the front, the snapshot shifts in a way that makes the object appear rotated.

"When we did the calculations, we were surprised how beautifully the geometry worked out," Hornof said. "Seeing it appear in the images was really exciting."

Editor's note: This article was updated on Tuesday (Oct. 14) at 11:15 a.m. ET to remove an innacuracy in a quote about Einstein's theory of relativity. We apologize for this error.

Larissa G. Capella is a science writer based in Washington state. She obtained a B.S. in physics and a B.A. in English creative writing in 2024, which enabled her to pursue a career that integrates both disciplines. She reports mainly on environmental, Earth and physical sciences, but is always willing to write about any science that sparks her curiosity. Her work has appeared in Eos, Science News, Space.com, among others.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus