The James Webb telescope proves Einstein right, 8 times over — Space photo of the week

The James Webb Space Telescope's latest image shows eight spectacular examples of gravitational lensing, a phenomenon that Albert Einstein first predicted some 100 years ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

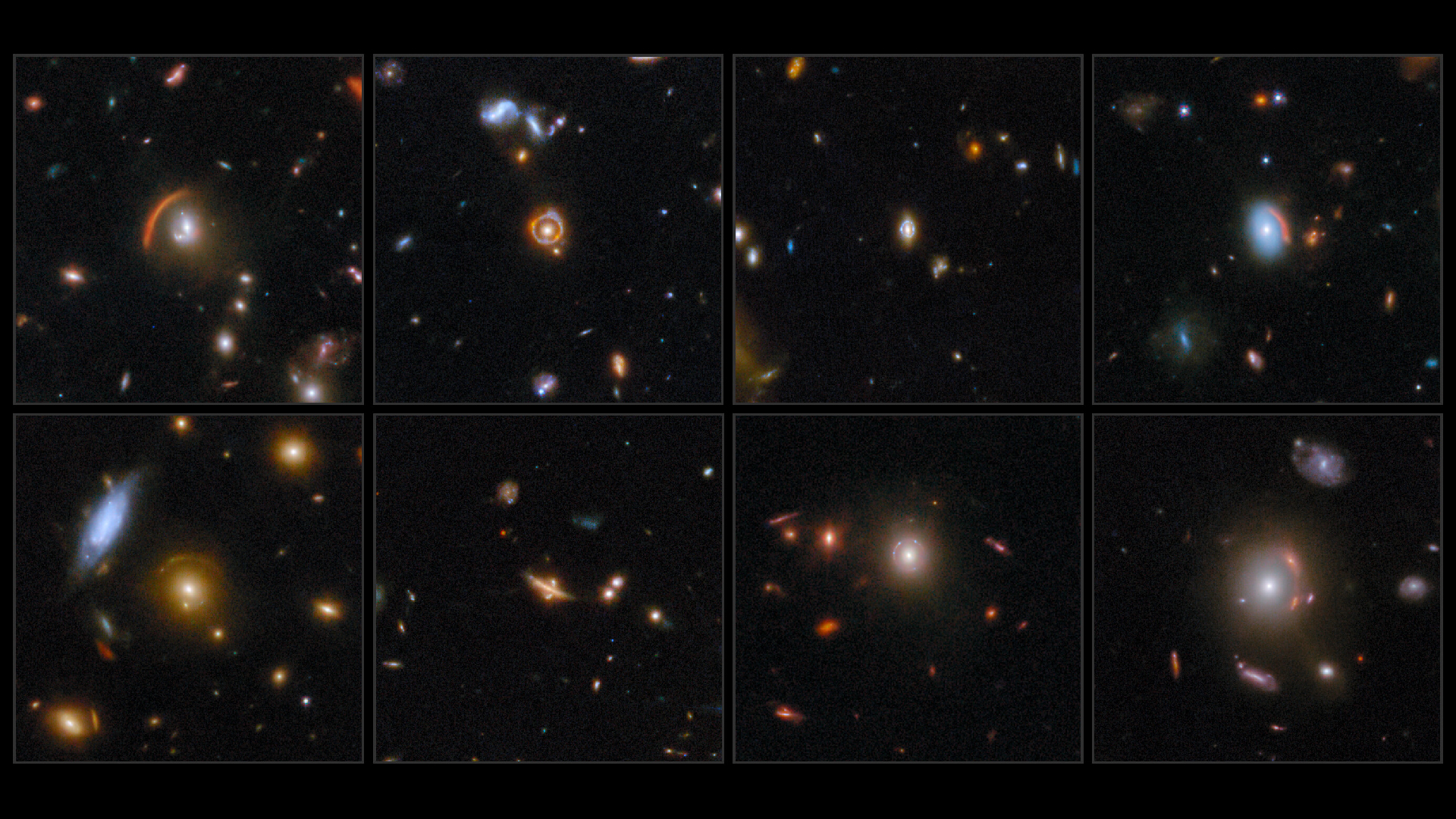

What it is: Eight "Einstein rings," officially known as gravitational lenses

Where it is: The deep sky

When it was shared: Sept. 30, 2025

As telescopes peer into the universe, they sometimes see quirks of nature that magnify faraway objects. These eight galaxies recently imaged by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) appear stretched, warped or even bent into perfect circles.

The odd shapes aren't camera tricks. They're caused by a cosmic effect called gravitational lensing, which turns massive galaxies into natural magnifying glasses.

Imagine space as a stretchy fabric. When a massive object, such as a galaxy, sits on that fabric, it bends the space around it. When light from a more distant galaxy passes through this warped space, its path curves. When the alignment is just right, that background galaxy's light is distorted into arcs or rings. The effect can create a glowing circle of light called an Einstein ring, named after Albert Einstein, who predicted this strange phenomenon more than 100 years ago. However, partial arcs and rings are more common.

Gravitational lensing helps astronomers see farther and clearer than ever before. These lenses magnify and amplify light from very distant galaxies that would otherwise be invisible. They also allow scientists to measure the mass of galaxies, including mysterious dark matter that can't be seen directly.

These spectacular new deep-field galaxy images come from a project called COSMOS-Web, one of the largest observing programs carried out with JWST. Scientists spent 255 hours pointing the telescope at more than 42,000 galaxies and found more than 400 possible examples of Einstein rings. The eight here are some of the most dramatic.

Perhaps the standout is the second image along the top. It shows COSJ100024+015334, a perfect circle that reveals a galaxy as it existed when the universe was just a billion years old — a fraction of its current estimated age (more than 13 billion years old).

Some of the galaxies had been seen before with the Hubble Space Telescope, but JWST's sharper infrared vision reveals details that were completely hidden until now. Others are brand-new discoveries, including galaxies made red by dust and distance.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The rare alignments that create Einstein rings allow astronomers to study the building blocks of galaxies, star clusters and exploding stars. These windows into the distant past reveal how galaxies formed and how dark matter shaped the cosmos in its early years.

For more sublime space images, check out our Space Photo of the Week archives.

Jamie Carter is a Cardiff, U.K.-based freelance science journalist and a regular contributor to Live Science. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners and co-author of The Eclipse Effect, and leads international stargazing and eclipse-chasing tours. His work appears regularly in Space.com, Forbes, New Scientist, BBC Sky at Night, Sky & Telescope, and other major science and astronomy publications. He is also the editor of WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus