5 Reasons Why Placentas Are Amazing

A grow-as-required organ

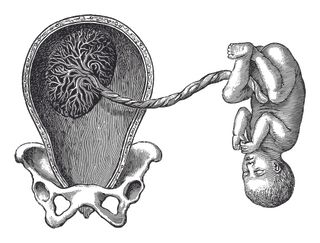

The placenta is a bowl-shaped mass of tissue with branching blood vessels that acts as a life support system for a fetus. It forms in the uterus at a pregnancy's start and grows over approximately 40 weeks of pregnancy. The placenta attaches to the uterine wall at the top or side and connects to the fetus through the umbilical cord, which supplies the fetus with oxygen and nutrients, and carries waste away.

It is the only organ that reproductive-age humans grow entirely from scratch. But there is also much about the placenta that scientists are just discovering, as they clarify the mechanisms through which it nourishes and sustains a fetus in utero, and how it may regulate body functions related to not only pregnancy, but also the lasting health of the mother after birth.

Here are just a few reasons why the placenta is so fascinating.

Predictor of postpartum depression

A hormone released by the placenta is associated with postpartum depression when found in high quantities prenatally, researchers reported in a study presented in May 2013 at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Although the findings did not suggest that the hormone — called placental corticotropin-releasing hormone (pCRH) — was a cause of postpartum depression, they did show that elevated levels of pCRH during pregnancy could serve as an early warning signal that a woman might be at risk for depression after the baby is born, the study authors explained.

Kick-starts labor

What triggers labor? The answer to this long-unsolved mystery might lie in gene expression within the placenta.

Levels of a substance known as a corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) increase in the body during pregnancy, incrementally over time. And high levels of CRH are known to be present when labor starts, suggesting that the hormone plays a role in signaling the body that it is ready to give birth.

When CRH is produced in the placenta, it triggers the release of another hormone that stimulates the placenta to produce even more CRH, suggesting that the placenta is a vital part of the biological "clock" that marks the end of pregnancy and the beginning of labor, according to a study published in August 2015 in the journal Science Signaling.

Defines the bulk of the mammal family tree

Most of the living mammals are placental mammals; the group includes more than 5,100 species. They arose from a common ancestor that emerged soon after nonavian dinosaurs went extinct, about 65 million years ago.

Scientists reconstructed this creature — called a "hypothetical ancestor," because no fossils of it exist — by using a computer program called MorphoBank to generate a roster of traits representing DNA and morphological data from known placental mammals, and then mapping them to a point in the family tree that would have marked their earliest appearance.

The so-called "mother of all placental mammals" is thought to have been an insect-eater about the size of a squirrel, with an elongated skull and a long, furry tail.

Inspires wound-healing technology

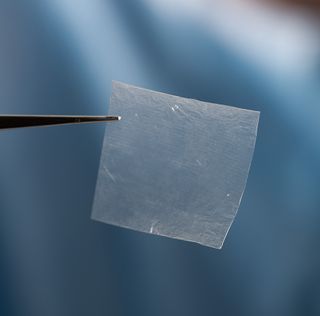

Surrounding the placenta is a thin, protective layer known as the amniotic membrane, an intricate scaffold of proteins that carries nutrients and stem cells for fetal development. Scientists are testing the amniotic membrane as a covering for open wounds that are slow to heal, an idea that was first explored in 1910.

Concerns over the possible transmission of blood-borne diseases such as HIV caused research on amniotic membranes to decline in the 1980s and 1990s. But recently, improved sterilization methods reinstated its use for treating diabetic ulcers and as biological dressings in eye surgeries.

You can eat it (but that doesn't mean you should)

Placentophagia — consuming the placenta after birth — is an established behavior that has been observed among mothers in most placental mammal species, except those that are semiaquatic or fully aquatic, according to a study published in February 1980 in the journal Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews.

And some human societies observe rituals based around preserving and eating the placenta, Mark B. Kristal, a psychology professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo, wrote in the study.

The notion of eating the placenta after childbirth — raw or cooked — or taking pills made from powdered placenta has risen in popularity in recent years, and the practice is rumored to help with breastfeeding difficulties or postpartum depression. Celebrity Kourtney Kardashian publicly championed the "life changing" powers of placenta-eating in a January 2015 post on Instagram.

However, researchers who analyzed 10 scientific studies found that there were no measurable health benefits to human mothers from eating placenta, according to findings published in October 2015 in the journal Archives of Women's Mental Health.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.