Total lunar eclipse this Wednesday will make supermoon turn blood red

The lunar eclipse happens on Wednesday, May 26.

If the full moon looks unusually large and reddish this Wednesday (May 26), don't be weirded out; count yourself lucky for catching the only total lunar eclipse of 2021.

May's full moon has a lot going on. In addition to the total lunar eclipse, which earns it the name "blood moon," because it will have a reddish tint, this moon is a supermoon and the closest full moon of the year, beating out April's full moon by 98 miles (157 kilometers), meaning it will appear infinitesimally larger to skywatchers on Earth. What's more, May's full moon is known as the Flower Moon, named for the wildflowers blooming in the Northern Hemisphere.

As with any lunar eclipse, questions abound: What's the best time and place to see the supermoon and the total lunar eclipse? Why will the moon appear red? Is it worth it to get special binoculars or a telescope? Read on to find out.

Related: Glitzy photos of a supermoon

On May 26, the moon will reach its fullest at 7:14 a.m. EDT (1114 UTC). However, the full moon reaches perigee, or its closest distance to Earth, the day before at 9:21 p.m. EDT on Tuesday, May 25 (0121 May 26 UTC), according to Space.com, a sister site of Live Science. Usually, the moon is an average of 240,000 miles (384,500 km) from Earth, but at that moment, the full moon will be 222,022 miles (357,311 km) from Earth, Heavens Above reported, making it a supermoon.

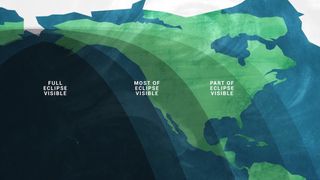

Most people, however, will have their eyes peeled for the total lunar eclipse. Weather permitting, skywatchers in the following places will see the moon become totally eclipsed by Earth's shadow and turn a rusty red for about 14 minutes: Australia, parts of the western United States, western South America and Southeast Asia, according to timeanddate.com. But other areas of the world and all of the United States will be able to see at least parts of the lunar eclipse, including its partial and penumbral phases.

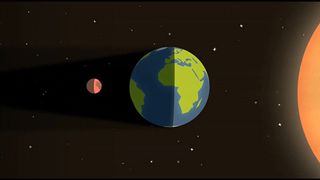

During a lunar eclipse, the Earth passes between the moon and the sun, meaning that Earth's shadow falls on the moon. Typically, the moon is full and bright when opposite the sun, because the moon's orbit is tilted about 5 degrees from the plane of Earth's orbit, so it avoids Earth's shadow, Space.com reported. Sometimes, including on May 26, the moon falls into one or more of Earth's shadows: Earth's outer, faint penumbral shadow, which leads to a penumbral eclipse, and Earth's inner dark shadow, known as the umbra, which can lead to a partial or total lunar eclipse.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If the moon is only partly in the umbra, skywatchers are treated to a partial eclipse. But once the moon is entirely within the umbra, or Earth's darkest shadow, it will reach totality, Space.com reported. At this time, the moon will appear to be rusty red. This happens because even though the Earth is blocking the moon from the sun, the sun's light still goes around Earth; this light travels through our atmosphere, which filters out shorter wavelengths, such as blue, but lets red and orange wavelengths through, Live Science previously reported. These long reddish wavelengths then hit the moon, making it appear a dull burgundy.

The entire eclipse will last for about five hours. Here's a schedule to keep handy: the penumbral eclipse begins at 4:47 a.m. EDT on May 26 (0847 UTC); next, the partial eclipse starts at 5:44 a.m. EDT (0944 a.m. UTC); then the full eclipse happens at 7:11 a.m. EDT (1111 UTC) and lasts for about 14 minutes, ending at 7:25 EDT (1125 UTC). In the middle of that, the maximum eclipse happens at 7:18 EDT (1118 UTC).

After that, the eclipse will start to wind down. The partial eclipse ends at 8:52 a.m. EDT (1252 UTC) and the penumbral eclipse ends at 9:49 a.m. EDT (1349 UTC), signaling the end of the Flower Moon's eclipse, according to timeanddate.com. In New York, only the initial penumbral eclipse will be visible because the sun rises at 5:31 a.m. EDT that day, according to sunrise-and-sunset.com.

Unlike the Great American Solar Eclipse of 2017, when it wasn't safe to look at the sun, it's perfectly fine to look directly at the moon during the lunar eclipse. As for gear, you'll get a great view with no tools at all. But, if you have them on hand, binoculars can help you see the moon's rough terrain, while a telescope will help you zero in on distinct features, such as cracks in the moon's surface known as rilles, which formed when ancient lava on the moon once filled basins before cooling and contracting, NASA reported.

Whether or not you see Wednesday's super Flower blood moon, be sure to mark your calendars for the next big lunar event, a partial lunar eclipse, will happen on Nov. 19, 2021.

Editor's Note: Live Science would like to publish your blood supermoon photos! If you snap an impressive shot of May's full moon and/or the lunar eclipse, email us the image at community@livescience.com. Please include your name, location and a few details about your viewing experience that we can share in the caption.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.