Snapshot of Hawaii: Why NASA Is Studying Islands' Volcanoes & Reefs

MARINE CORPS BASE HAWAII — Whether it's the noxious gases rising from the Kilauea volcano, or the lively coral reefs that sprawl across the seafloor around the island chain, Hawaii's ecosystems are under some serious scientific scrutiny this month.

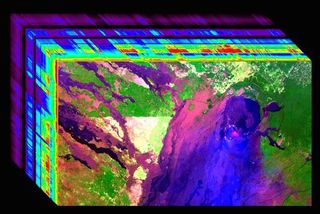

Researchers are here gathering data using NASA's high-altitude airplanes, outfitted with cameras that capture visible light as well as infrared radiation. One airplane, the ER-2, can soar to 67,000 feet, or "the edge of space," as NASA systems engineer Michael Mercury put it. From that height, on daily flights over the islands, the cameras snap images that the scientists then stitch together and analyze, Mercury said, explaining the project at a media briefing that the space agency held here on Wednesday (Feb. 8). [Earth Pictures: Iconic Images of Earth from Space]

The goal of this current work in Hawaii is to find the best ways to use these measurements to gain new insights into volcanic activity and coral reef health. For example, scientists studying Hawaii's active volcano are trying to refine their models that predict exactly how and when the "vog," or volcanic smog that forms from Kilauea's gases, will blanket Hawaiian cities instead of blowing out over the Pacific. Other researchers, who study coral reef ecosystems, are using the images from the high-altitude flights to better understand what aspects of water quality make the difference between a thriving reef and one that is overgrown with algae.

But there is a larger goal, too. NASA has plans to launch an Earth-observing satellite into low-Earth orbit in 2022. That project, called the HyspIRI mission (or Hyperspectral Infrared Imager), will provide researchers with images of Earth's surface that are similar to those being gathered now in Hawaii, and from ecosystems all over the world.

The current project in Hawaii will help the researchers to figure out exactly which instruments and equipment are most useful for their work, and should be the ones that are loaded up onto that satellite.

Eventually, the satellite could be used to gather data not only on volcanoes and corals, but also on many other features that change the Earth's surface over time, such as wildfires that destroy vegetation, thinning glacial ice or changes in the health of croplands.

Once the HyspIRI satellite is in place, researchers plan to use it in conjunction with aircraft- or ground-based instruments. "The satellite might see something new, [and] point us to new places to go with the airplane," Randy Albertson, deputy director of the NASA Airborne Science Program, told Live Science. [Colorful Creations: Incredible Coral Photos]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the meantime, the Hawaii projects are in full swing. In the coral project, the images taken by the instruments aboard the aircraft can help the researchers spot changes in the color of a reef, said Steven Ackleson, an oceanographer with the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C., who is in Hawaii to work on the project.

"Reef pigments come from both the zooxanthellae and from the corals themselves," Ackleson told Live Science, using the scientific term for the algae-like organisms that live in symbiosis with the coral polyps. "Colors indicate health," he said.

The researchers want to figure out the best ways to draw information from the images to determine coral health, he said. For example, the scientists are hoping to learn more about why some types of zooxanthellae tolerate warming waters better than others. The answer may involve differences in the chloroplasts between the different types of zooxanthellae, he said.

The researchers who are working on the volcano project are using the images to better study the composition of the gas plume that arises from Kilauea, and how it changes as the plume spreads out, said Vincent Realmuto, a geoscience researcher at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

A key part of the project is looking at how the plumes affect Hawaii's air quality, Realmuto said.

For example, one question the volcano researchers are trying to answer with the new data is exactly how quickly the sulfur dioxide gas that the volcano emits becomes aerosolized, meaning it combines with other compounds to form particulate matter, which can be harmful to human health.

The current estimate is that process takes 10 hours, Realmuto said. But that estimate is very rough. "The local temperature, the humidity, the topography – all of these impact the conversion rate," he said. The new data will help the scientists to create better models to predict the formation and movements of the particulate matter, which could lead to better forecasts of the vog. [The 10 Biggest Volcanic Eruptions in History]

Albertson noted that even when it launches, the new satellite won't eliminate the need for gathering data from instruments aboard aircraft and on the ground. Ground-based instruments can gather measurements on a much finer scale than the satellite will. But the satellite's capacity to get images from the entire Earth in a short amount of time will be a huge advantage for researchers.

To put this in perspective, Mercury said, the current six-week effort will capture images, using the visible-light camera, for most of Hawaii. If that camera were on a satellite, for the same amount of time, the researchers would be able to capture the same level of imaging for the entire Earth's surface, four times over, he said.

Originally published on Live Science.