7 Amazing Archaeological Discoveries from Egypt

Uncovering Egypt

From the boy-king's glitzy tomb to the Rosetta stone, which was written by a council of priests, to the pyramids at Giza, to papyri holding gospels and magical spells, Egypt holds a vast and mysterious trove of history with interesting stories to tell. Archaeologists continue to discover these ancient sites and artifacts. Here, Live Science takes a look at seven of the most amazing finds from Egypt.

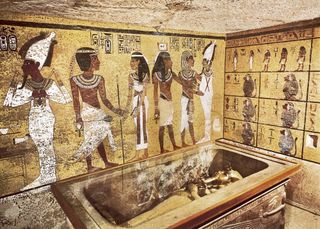

King Tut's tomb

The tomb of Tutankhamun in Egypt's Valley of the Kings is, arguably, the most famous archaeological discovery ever made. Unearthed in 1922 by a team led by Howard Carter, the tomb was filled with fantastic treasures, including Tutankhamun's death mask, which today is practically an icon.

Carter entered the tomb on Nov. 26, 1922: "As one's eyes became accustomed to the glimmer of light, the interior of the chamber gradually loomed before one, with its strange and wonderful medley of extraordinary and beautiful objects heaped upon one another," he wrote in his diary as he struggled to describe the wonders he saw that day.

The boy king, as Tutankhamun is sometimes called, died in his teens. Analysis of his remains suggests that he suffered from a variety of health problemsand used a cane to walk around. He spent much of his rule (ca. 1332 B.C - 1323 B.C.) trying to restore Egypt's traditional polytheistic religion, something that had been interrupted when his father, the pharaoh Akhenaten, started a revolution that emphasized the primacy of the Aten, the sun-disc.

When Tutankhamun's tomb was discovered, it sparked a media frenzy and a rumor that opening the tomb had unleashed a curse.

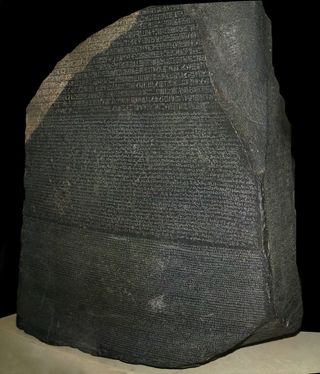

Rosetta Stone

Dating to 196 B.C., the Rosetta Stone holds a decree written by a council of priests that affirms the right of pharaoh Ptolemy V (who was 13 years old at the time) to rule Egypt.

What makes the Rosetta Stone remarkable is that the decree was written in three languages: hieroglyphic, Demotic and Greek. When the stone was discovered in 1799, only the Greek language was known, but because the Greek inscription communicated the same decree as the other two languages, it helped scientists decipher those tongues. This allowed for texts written in hieroglyphic and Demotic to be read.

A scientific team that was accompanying a military expedition led by Napoleon found the stone in 1799. The British later captured the stone, which is now in the British Museum. The Egyptians have asked Britain to return the stone to Egypt.

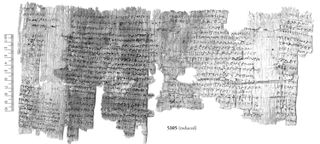

Oxyrhynchus Papyri

Between 1896 and 1907, archaeologists Bernard Grenfell and Arthur Hunt discovered over 500,000 papyri fragments, dating back around 1,800 years. The investigators found the fragments in the ruins of Oxyrhynchus, a sizable ancient town in southern Egypt that flourished at a time when the Roman Empire controlled Egypt. The town's arid conditions meant that the papyri used by residents survived nearly 2 millennia.

The papyri include Christian gospels, magical spells and even a contract to fix a wrestling match.

Today, the United Kingdom's Egypt Exploration Society (which sponsored the Grenfell and Hunt expeditions) owns many of the papyri, keeping them at the University of Oxford. Scholars have been analyzing and translating the papyri ever since the fragments were discovered, but the sheer number of texts means that many are still unpublished.

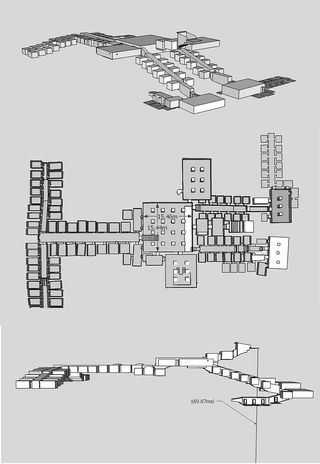

Pyramid town at Giza

Since 1988, a team of archaeologists from AERA (Ancient Egypt Research Associates) has been excavating a town near the Pyramid of Menkaure, on the Giza Plateau. The pyramid for the pharaoh Menkaure (who reigned from roughly 2490–2472 B.C.) was the last pyramid constructed at Giza, and the people who lived at Giza would have been involved in building the structure.

The discoveries made at the town include barracks for soldiers, agiant house for senior officials and a port for importing goods. The discoveries provide a vast amount of information about the people who built the pyramids and the logistics behind pyramid construction, such as how the pyramid builders were fed.

Tomb KV5

In 1995, excavations at KV5 revealed that the little-studied tomb was actually the largest ever constructed in the Valley of the Kings. Excavations are ongoing and at last report, archaeologists had found 121 corridors and chambers in the tomb; the researchers said they think more than 150 will eventually be found.

Archaeologists found that the tomb was used to bury the sons of pharaoh Ramesses II (reign 1279-1213 B.C.).

"At least six royal sons are known to have been interred in KV5. Since there are more than 20 representations of sons carved on its walls, there may have been that many sons interred in the tomb," wrote archaeologists from the Theban Mapping Project in a reportpublished on the group's website.

The Silver King

In 1939, archaeologist Pierre Montet discovered the tomb of Psusennes I, a pharaoh who ruled Egypt around 3,000 years ago. His burial chamber was located in Tanis, a city on the Nile Delta. The pharaoh was buried in a coffin made of silver and was laid to rest wearing a spectacular gold burial mask, Montet found. (Psusennes I is sometimes called the "Silver King" because of his silver coffin.)

Because of the delta's humidity, some of the grave goods did not survive; however, canopic jars (used to store some of the pharaoh's organs) and shabti figurines (meant to serve the king in the afterlife) were also discovered. Because the tomb was discovered when the Second World War was starting, it received little media attention.

Pyramid-Age papyri

In 2013, a team of archaeologists led by Pierre Tallet and Gregory Marouard announced the discovery of a port built along the Red Sea about 4,500 years ago, during the reign of the pharaoh Khufu. Among the finds are papyri that discuss the building of the Great Pyramid at Giza, the largest pyramid ever constructed.

The papyri say that limestone, used in the outer casing of the Great Pyramid, was shipped from a quarry at Turah to Giza along the Nile River and a series of canals. One boat trip between Turah and Giza took about four days, the papyri say. The papyri also shed light on how long Khufu ruled Egypt, and reveal that in the pharaoh's 27th year of rule, a vizier named Ankhhaf was in charge of pyramid construction.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.