Frogs 'Talk' Using Complex Signals

Frogs are known for producing a wide range of sounds, and they certainly aren't shy about piping up to win mates or warn intruders off their territory. But some types of frogs have a broader "vocabulary" than others, combining different vocalizations with gestures to say, "Come hither!" or "Keep your distance!"

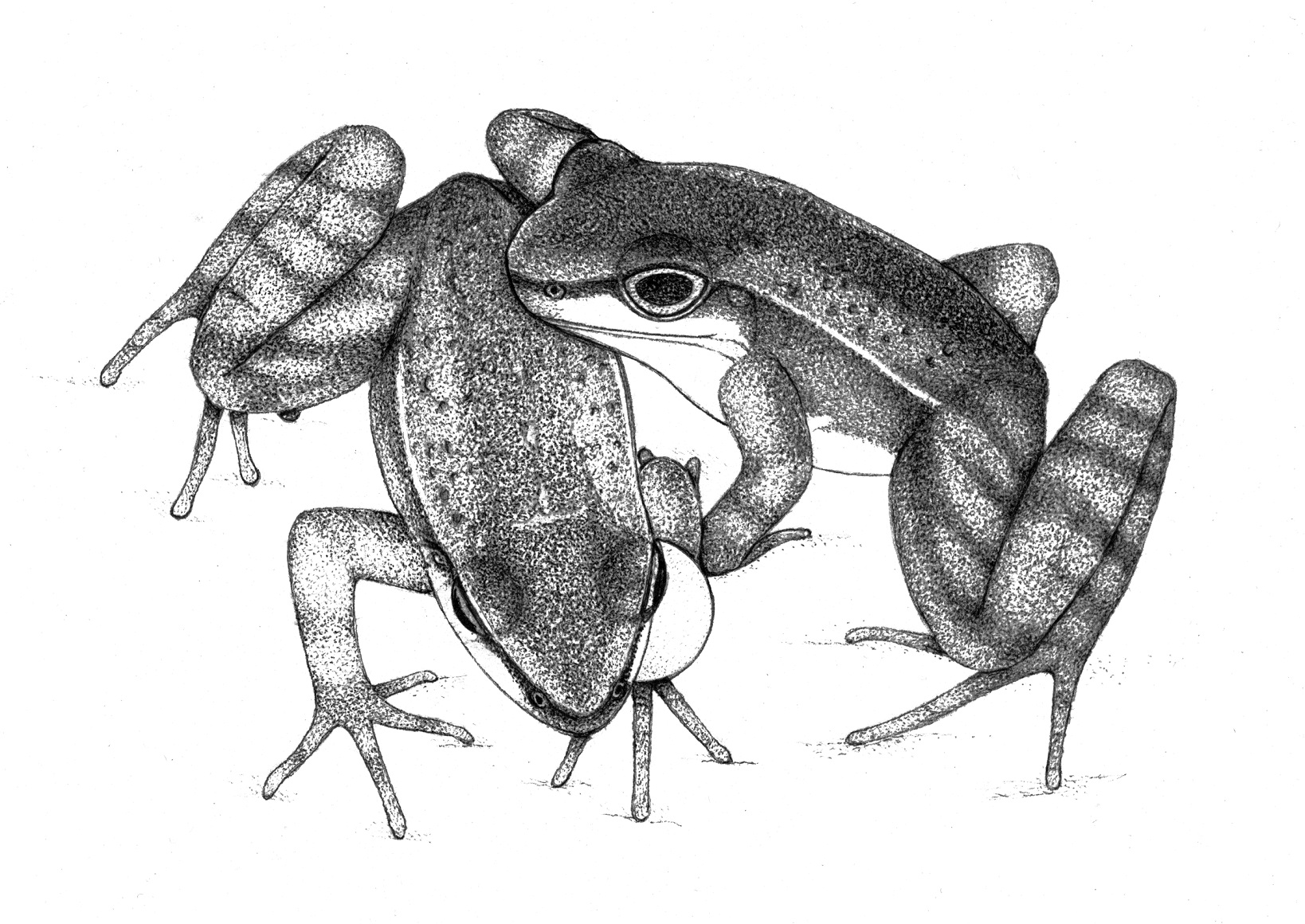

A recent study of a Brazilian torrent frog, Hylodes japi, shows that this species employs a more nuanced communication system than any other known frog species. These outgoing amphibians use a combination of tactile, vocal and visual signals — including squealing, head bobbing and alternate-arm waving — to get each others' attention, the scientists said.

In fact, researchers found that the tiny H. japi had a sizable repertoire of calls and displays that was more complex than any seen before in anurans, the animal order that includes frogs and toads. The species' "vocabulary" included five visual displays never seen before in anurans at all. [Video: Brazilian Frogs Talk with More Than Just Voices]

Scientists have long recognized that vocal calls are frogs' chief means of communication, but recent studies detail a growing body of evidence for visual cues used in communication among several frog species, said the study authors. This is especially true for species that are diurnal, or active during the day, and which breed in noisy environments, the investigators said. Diurnal, stream-dwelling Brazilian torrent frogs would thereby be good candidates for studying visual displays, the authors said they suspected.

"Torrent frogs" is a broad term that describes a diverse collection of frog species that inhabit fast-flowing creeks and streams in mountains and hills around the world. They tend to be small, with mottled grey-brown coloration that camouflages the amphibians among wet earth and stream beds, and they are well-adapted to adhere to wet, slippery rocks, clinging with specialized toe pads and the skin on their bellies and thighs.

The torrent frog in the new study, H. japi, is found in Brazil's Serra do Japi forest in the state of São Paulo, and was only recently discovered. The frog was first described in Dec. 2015 by the current study's lead author, Fábio de Sá.It is slender-bodied, generally measuring between 0.9 inches and 1 inch (23 and 28 millimeters) in length, with females somewhat larger than males.

Call center

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Frogs' calls provide some of the clues that biologists use to tell species apart, said de Sá, who is a Ph.D. candidate at São Paulo State University (Universidade Estadual Paulista). De Sá told Live Science in an email that when he and his colleagues first discovered the frogs, the animals' array of communication techniques helped the scientists understand that they were seeing, and hearing, something completely new.

"We noticed the complex repertoire and that we were dealing with a new species," de Sá said.

For the study, the scientists observed 68 frogs, including males and females, in their habitats, making 17 trips to the Serra do Japi forest in 15 months. The researchers noted that males would call during all months except October, and that during breeding season, between February and April, the competition and interactions between males became "intense."

"From the moment the resident male hears intruders' calls or sees an intruder male, he starts to direct visual signals to the invader," de Sá told Live Science.

Let's dance

Some of the frogs' displays, like certain types of walking and jumping, were similar to those seen in other frogs. But as the researchers tallied the signals for territory disputes and for mating, the list kept growing. Toe wagging and leg stretching? Check. Arm lifting and waving? Added. And hand shaking and body jerking and alternate vocal sac inflation and peculiar walking … the list went on and on, far longer than is typical for most species of frogs, the scientists said.

And then things really got weird. Male frogs pushed off from the ground with their arms to elevate the front parts of their bodies. They bobbed and wove their heads from side to side in snakelike figure-eight patterns. While sitting, they picked their feet up and showed their toes. Some of these displays were for courtship, some were warnings to rival males and some were used for both. None had ever been observed in frogs before, the researchers found.

The males used their voices, too, with a vocal playlist that included peeps, squeals and a special courtship call made up of five notes. Altogether, the researchers recorded 18 distinct communication signals that involved some sort of vocalization or display action. Males and females even shared special tactile signals, something else that was previously unknown in frog courtship. Males peeped courtship calls in response to a female's touch. [Freaky Frog Photos: A Kaleidoscope of Colors (Gallery)]

The study, de Sá said in a statement, shows that not only is communication in this species "more sophisticated than expected," but also suggests that communication among all frog species is more complex than once regarded. This is especially true in tropical areas, where greater diversity could drive species to evolve highly specialized signals to distinguish their own kind, de Sá said.

So the next time you eavesdrop on the chirping tones of a frog chorus, remember: Their conversation is probably more meaningful, and more ribbit-ing, than you'd think.

The findings were published online today (Jan. 13) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.