Get a Grip: How Frogs Hold on in Flowing Water

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Torrent frogs have an amazing ability to climb in wet environments near waterfalls, where ordinary tree frogs would be washed away.

Researchers compared the gripping ability of torrent frogs, a class of frogs that live in fast-flowing mountain or hill streams, to that of tree frogs, and found that torrent frogs were much better at gripping wet, steep and rough surfaces.The frogs' sticky secret, the researchers found, involves hugging wet and rough surfaces with their toes, belly and thighs.

"Torrent frogs adhere to very wet and rough surfaces by attaching not only their specialized toe pads (like many tree frogs do), but also by using their belly and ventral (inner) thigh skin," study researcher Thomas Endlein, of the University of Glasgow in Scotland, wrote in a statement. [40 Freaky Frog Photos]

Tree frogs can climb smooth surfaces, thanks to capillary forces between the fluid molecules between the wet surfaces and the frogs' toe pads. Yet, puzzlingly, torrent frogs can cling to surfaces even when there's enough water to destroy this adhesive boundary.

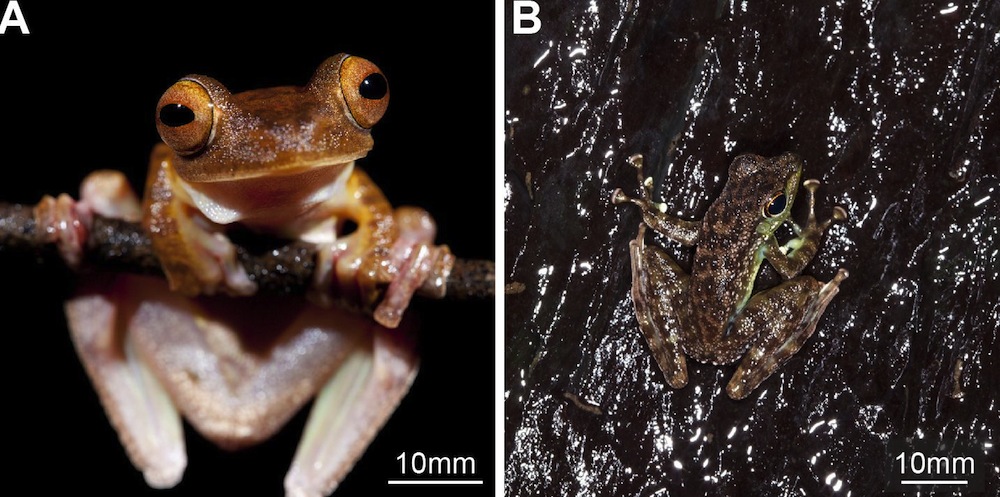

Endlein and his colleagues decided to put the amphibians' incredible sticking abilities to the test. They placed a species of torrent frogs (Staurois guttatus) and trees frogs (Rhacophorus pardalis) on a platform that could be tilted from horizontal to upside-down, and tested how long the animals could cling at different angles, levels of roughness and water flow.

On dry, smooth surfaces, both frogs hung on equally well. But on wet surfaces, at both high and low flow rates, the torrent frogs adhered at steeper angles than the tree frogs — even when their toe pads were submerged in water, results showed.

The rotating platform was transparent, allowing the scientists to measure the areas of the frogs' bodies in contact with the surface.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In addition to their pads, both frog species appeared to use large parts of their bellies and thighs to get a grip. But whereas the tree frogs' bellies and thighs detached from the platform at steeper angles, the torrent frogs increased their use of these body parts.

Measurements from a force transducer showed the forces on different skin parts weakened in wet conditions by nearly the same amount in both types of frog, suggesting the torrent frogs' better grip was due to the greater body area in contact with the surface.

Using a scanning electron microscope, the researchers also found that the toe pads of torrent frogs are equipped with elongated cells on their edges, with straight channels in between. These channels could allow excess water to drain away, helping the frogs keep their grip.

The study was detailed today (Sept. 25) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus