Photos: America's Only Lake Titicaca Frogs

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Rare frog

One of three critically endangered Lake Titicaca frogs on display at the Denver Zoo, the only place in the northern hemisphere where these amphibians are on view for the public. These frogs are endemic to Lake Titicaca, a high-elevation lake on the border of Peru and Bolivia. They're endangered in large part because they're the main ingredient in "frog juice," a blended concoction that's supposed to improve virility and health.

Strange skin

This juvenile frog at the Denver Zoo is small enough to fit in the palm of a hand, but Lake Titicaca frogs can grow to the size of dinner plates and weight more than 2 pounds (1 kilogram). They live a fully aquatic lifestyle and breath through their skin. The excess folds allow them to absorb extra oxygen from the cold waters of Lake Titicaca, which vary between 50 degrees and 60 degrees Fahrenheit (10 to 17 degrees Celsius).

Lake Titicaca Native

Twenty Lake Titicaca frogs arrived at the Denver Zoo in November 2015 and three were put on display in the spring of 2016. The frogs are the second-generation descendants of wild-caught Lake Titicaca frogs rescued from markets in Lima and other cities in Peru. Poaching is a major threat to the species, along with competition and predation by introduced fish species to the lake. Pollution run-off and a deadly skin fungus called chytrid also conspire to land these animals on the "critically endangered" list.

Wild Frog

A juvenile Lake Titicaca frog in its native habitat. Lake Titicaca sits at 12,500 feet elevation (3,811 meters). It's cold, has a high pH and a high mineral content — not, on the surface, an ideal environment for frogs, said Tom Weaver, the assistant curator of reptiles and fish at the Denver Zoo. Lake Titicaca frogs have adapted to this extreme environment by evolving saggy skin to let them capture more oxygen from the water.

Big frogs

Lake Titicaca frogs are the largest totally aquatic frogs in the world. Older, larger frogs tend to live deeper in the lake and can be harder to find than the juveniles who stay closer to the shoreline. The Lake Titicaca frog is critically endangered, meaning that likely less than 80 percent of its historical population remains.

Fieldwork at Lake Titicaca

Denver Zoo outreach specialist James Garcia holds a wild Lake Titicaca frog during fieldwork in Peru. Researchers can scuba dive to about 10 meters (33 feet) in the lake, but can't go lower because of the lack of medical care in the region should something go awry. Garcia is part of an education effort with local high school students to build an underwater remotely operated vehicle equipped with cameras that will be able to dive to 100 meters (328 feet) to survey frog populations.

Lake Titicaca's Diversity

Lake Titicaca frogs can vary in size and coloration, but researchers still have lots of questions about their biology and life cycle. There are now captive breeding populations in Peru and Bolivia, and conservationists hope that the Denver Zoo frogs will breed as well. If they do, some frogs are likely to be transferred to other U.S. zoos, said Tom Weaver, the assistant curator of reptiles and fish at the Denver Zoo.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Frogs on Display

Three Lake Titicaca frogs are on display in this tank at the Denver Zoo. The water is kept chilled to 60 degrees F (17 degrees C) and a back-up chiller is ready to spring into action in case the first chiller breaks. Frogs are extremely sensitive to temperature and chemical fluctuations in their water, said curator Tom Weaver. They're easy to keep alive in captivity — as long as their environment stays within precise parameters.

Denver Zoo Frogs

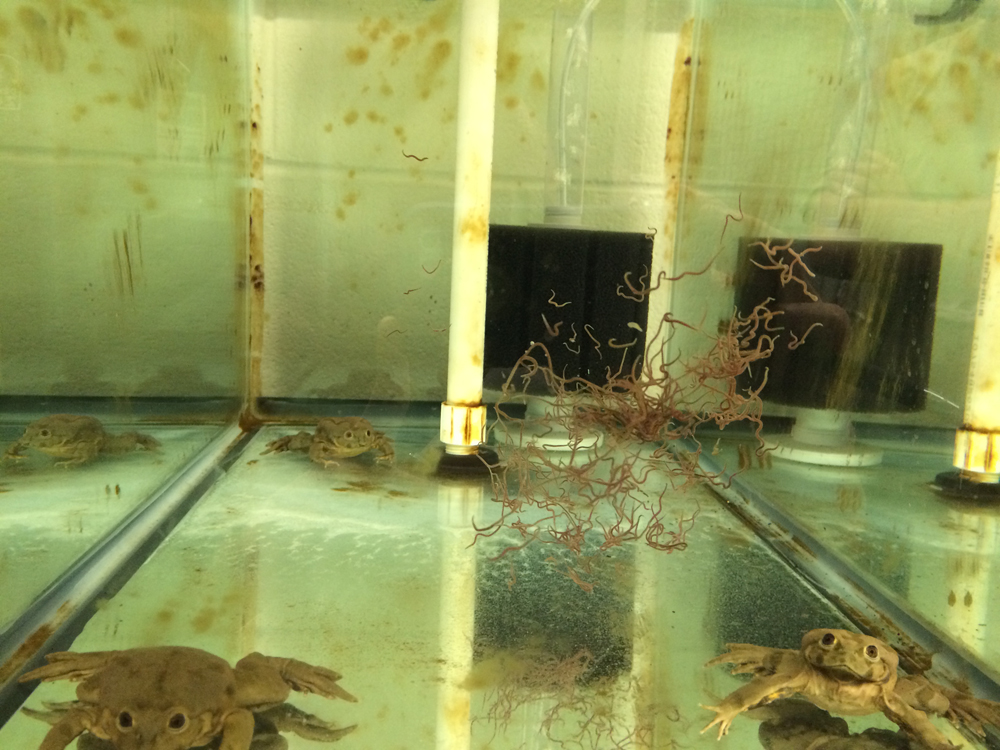

Two Lake Titicaca frogs blend in with their surroundings at the Denver Zoo. The frogs often rest on the bottom of the tank and execute small hops that look like push-ups. This movement pushes water over their skin and lets them absorb more oxygen. They live off a diet of worms, especially threadlike red wigglers.

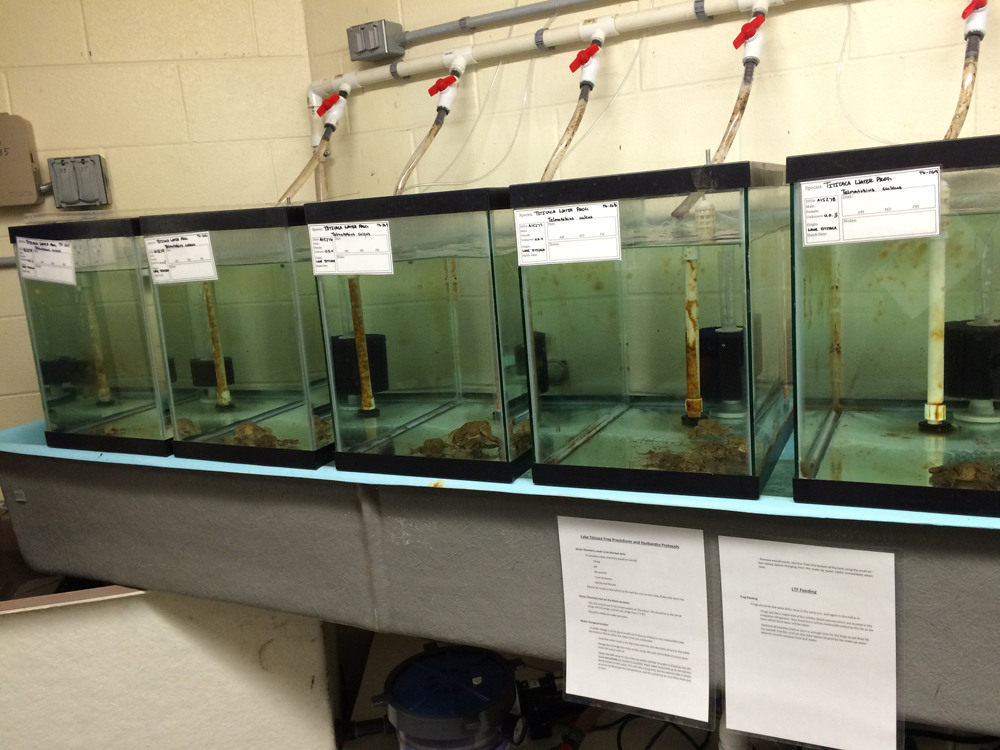

Lake Titicaca Collections

Only three of the Denver Zoo's 20 frogs are on display. The other 17 are kept in these tanks, flanked by a massive filtration system to keep their water clean and chemically consistent. So far, the frogs have lived in harmony with one another, Weaver said, though they do occasionally miscalculate when eating and nip each other's limbs.

Feeding Time

A Lake Titicaca frog perks up as a cloud of red wiggler worms falls to the bottom of its tank. The frogs have ravenous appetites. Their forward-facing eyes likely help them hunt visually, said outreach specialist James Garcia. The frogs blink as they swallow because they use the muscles around their eyes to help force food down their throats.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus