Toxic Lead Pollution Left Its Mark in Andes Mountains

Toxic lead buried in icy layers of an Andes glacier reveals that leaded gasoline was the region's worst polluter in the past 2,000 years, a new study reports.

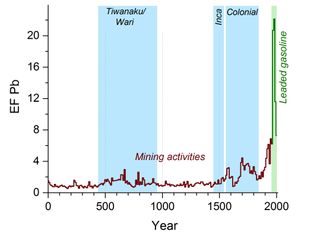

Traces of lead pollution from precolonial mines and metallurgy (such as the extraction of silver and other metals) are present in the glacier going back hundreds of years. For instance, the research team found spikes in lead pollution during the height of the Tiwanaku-Wari culture (450 to 950) and the Inca Empire (450 to 1532). Pollution levels also rose when invaders expanded the local silver and copper mines during colonial times (1532 to 1900), and when there was a tin boom in the early 1900s, according to the report, published March 6 in the journal Science Advances.

But the Swiss researchers discovered that lead levels tripled in the 1960s, when leaded gasoline was introduced, adding more lead pollution to the glacier than at any time in the past 2,000 years. The contamination levels dropped sharply after governments phased out the use of leaded gasoline, the report found.

"In the cradle of New World metallurgy, pollution from leaded gasoline dominates over lead emissions from mining and metallurgy," said Anja Eichler, lead study author and a research chemist at the Paul Scherrer Institute in Villigen, Switzerland. [10 of the Most Polluted Places on Earth]

The results come from lead isotopes trapped in ice at Bolivia's Illimani glacier, on the country's second-highest mountain, just south of La Paz. Lead from mining and metalwork produces ratios of lead isotopes that are different from fossil fuels lead isotope ratios, thus allowing the scientists to distinguish between the sources of pollution. (Isotopes are atoms of an element that have different numbers of neutrons.)

Lead is a neurotoxin that is harmful to both humans and the environment, Eichler said. The lead in the glacier was deposited by snow, capturing a record of past lead levels in the atmosphere. (Lead from gasoline spreads into the air via exhaust fumes, while lead from mining often travels on dust particles.)

Previous studies in ice cores from Greenland, Europ and Asia have also shown that atmospheric lead levels spiked after 1960, but this is one of the first studies to confirm the trend in the Southern Hemisphere. Similar evidence has been found in lake sediment cores, but the lakes are located close to the old mines. The ice core record from the remote Andes glacier confirms that atmospheric lead pollution reached distant regions of the Southern Hemisphere.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The research team now plans to measure other metals in the ice core, to see whether precolonial mining and smelting for gold, copper and zinc left a pollution record in the glacier.

"For me, it is fascinating to reveal the recent and historical environmental impacts from natural archives such as glaciers," Eichler said. "Hopefully, we can retrieve all of their stored information before they are gone."

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Most Popular