Sky River to Bust Northern California Drought This Week

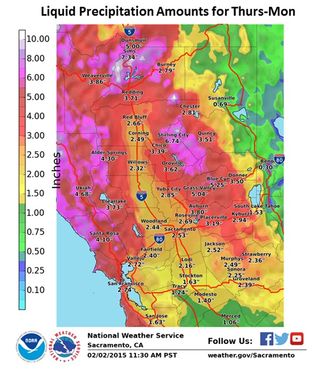

California forecasters are prepping the state's northern cities for a switch from extreme drought to drenching rain and damaging winds starting tomorrow (Feb. 5).

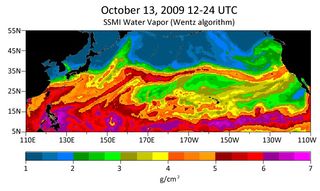

An incoming atmospheric river could deliver at least 10 inches (25 centimeters) of rain in coastal and inland mountains, and 5 inches (13 cm) in valley areas, according to the National Weather Service. Atmospheric rivers are narrow currents of warm, moist air that transport huge amounts of water vapor from the tropics toward cooler latitudes. The water is nearly invisible, just concentrated vapor that later condenses into rain and snow. That happens when the current hits land and the air is lifted and cooled over mountains like California's Coast Ranges and Sierra Nevada.

The storm arriving Thursday will be one of the most closely watched atmospheric rivers in history, as scientists plan to study the weather pattern from the ocean, in the air and on land. [In Images: Extreme Weather Around the World]

"This is unprecedented," said Marty Ralph, a meteorologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California, and a leader of the field campaign. "It's a major effort in our field to understand the processes that provide water in our state."

The $10-million field campaign, called CalWater 2015, represents a massive effort to unravel the mysterious processes that control atmospheric rivers. In California, atmospheric rivers are sometimes called drought-busters or the Pineapple Express, because the air currents deliver a deluge of tropical moisture that can ease severe droughts. The weather pattern has been recognized for decades, but major research efforts to understand atmospheric rivers weren't launched until 20 years ago, with the advent of satellites that could track atmospheric water vapor, Ralph said.

"That's when the light bulb went off," he said.

Scientists have now recognized atmospheric rivers around the world. The air currents occasionally deliver snow to desertlike East Antarctica. Warm air brought in by an atmospheric river boosted melting in Greenland in 2012, researchers think. Atmospheric rivers spawned in the North Atlantic often bring winter floods to Western Europe.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Forecasting storm impacts

But even forecasting where an atmospheric river will hit the West Coast remains a challenge, Ralph said. And in 2011, researchers discovered that aerosols — tiny particles in the atmosphere that come from pollution and natural sources — could influence how much rain is dumped during an atmospheric river.

"It was a pretty big surprise," said Kim Prather, a leader of the 2011 study and an atmospheric chemist at Scripps. "We thought aerosols would matter the least" in precipitation totals.

Four research airplanes equipped as flying laboratories will soar through the atmospheric river this week as part of the CalWater experiment, including one plane equipped to measure aerosols. Prather and climate modeler Ruby Leung of the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory will be on board the plane targeting the most likely patches of aerosols. "We beg to be up there," Prather said.

Two of the other planes spend their summers as hurricane hunters, and one will release dropsondes, miniature parachutes that record weather data on their downward trip. Finally, NASA's high-flying ER-2 aircraft, the civilian equivalent of the U-2 spy plane, will skim over the clouds at 45,000 feet (13,700 meters) above the surface.

The largest of NOAA's research ships is also part of the crew, having been stationed in the Pacific since January, waiting to catch an atmospheric river. Scientists on board that vessel are now positioned beneath this week's oncoming jet, with instruments that can measure factors such as air moisture, air pressure and wind. On land, existing weather networks will track the storm in concert with the research effort.

For California, atmospheric rivers can make or break a drought. Four to five of the storms typically arrive in California each year, but only one to two have made landfall in each of the last three years, a shortage that adds to the state's ongoing drought.

The most recent atmospheric river to arrive showed up in December, dumping almost 3.5 inches (9 cm) of rain on San Francisco. For comparison, there was no measurable rain in San Francisco in January, typically the city's wettest month of the year.

Atmospheric rivers "like the ones in Northern California are the equivalent of a hurricane," said Chris Fairall of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), who is studying atmospheric rivers from the sea as part of CalWater. In 1997, an atmospheric river triggered the "New Year's Day Flood" that soaked Northern California with more than 14 inches (36 cm) of rain, causing more than $1 billion in damages. [Top 10 Deadliest Natural Disasters in History]

The avalanche of data will help scientists create a 3D model of atmospheric rivers and the factors that govern their rainfall, such as aerosols and dust in the atmosphere. The results will also help to improve current forecast models, Ralph said. And the new data will refine climate models that predict how global warming will affect atmospheric rivers.

"We are going to use this kind of data to improve our ability to predict the future," Leung said.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.