Ancient 'alien goldfish' shot toothy 'tongue' out of its gut to catch prey

The 'alien goldfish' might just be an early mollusk.

Ancient creatures nicknamed "alien goldfish" had toothy, tongue-like structures in their guts that they fired out of their bodies to catch prey 330 million years ago, but they weren't so different from some modern-day mollusks in that regard, a new study finds.

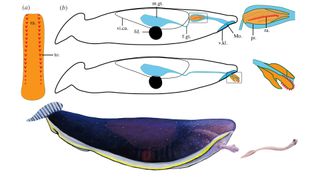

Toothed tongue-launcher Typhloesus wellsi was first described in 1973, and has been an evolutionary enigma in scientific circles for many decades. The freaky animal dates from the Carboniferous period (358.9 million to 298.9 million years ago). But fossils of the vaguely fish-like animals were so different from other Carboniferous animals that scientists joked they belonged to extraterrestrials. Now, thanks to some exceptionally well-preserved fossils in Montana, researchers have found that these so-called aliens have a feeding mechanism resembling that of mollusks — a large group of soft-bodied invertebrates that includes snails, clams and octopuses.

Many mollusks have a similar inverted tongue-like structure called a radula, which carnivorous and herbivorous members of the group use to grab food. The researchers, therefore, suspected that the mysterious T. wellsi was an early mollusk.

"We would like to think we've solved a small evolutionary conundrum," lead author Simon Conway Morris, an emeritus professor of paleobiology at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, told Live Science.

Related: Ancient toothless 'eel' is your earliest known ancestor

Conway Morris dubbed T. wellsi the "alien goldfish" in a 2005 article published in the journal Astronomy & Geophysics. He whimsically imagined the species arriving on Earth during the Carboniferous because a visiting intergalactic commodore grew tired of keeping them as pets and threw them into a lagoon, baffling human scientists who found their fossilized remains hundreds of millions of years later.

"Nobody seriously believed that they were extraterrestrial goldfish, but they certainly looked extremely strange," Conway Morris said. Along with the toothy gut tongue, T. wellsi had a soft body that measured up to 3.5 inches (9 centimeters) long, with a prominent fin at the back to propel them forward.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For the new study, researchers studied T. wellsi specimens acquired by the Royal Ontario Museum and saw that one of them had an exceptionally well-preserved set of teeth. The teeth weren't where a mouth would be on humans; rather, they were deep inside the body of the fossil and pointing backward.

The scientists concluded that the front end of the gut must have shot out of the body, inverting the position of the teeth to grasp prey — in other words, turning the predator's foregut inside out. Conway Morris compared this to a plastic glove with a pressed-in finger that's filled with water or blown into until the finger pops out. Researchers know that T. wellsi was an active predator because the remains of tiny worm-like prey called conodonts are found inside them.

The researchers proposed in the new study that T. wellsi was an early gastropod, which is the group of mollusks that includes modern snails and slugs, because many of these living species extend their foreguts to grasp prey. "It's the discovery of this radula-like structure, which we suggest is the really crucial piece of evidence," Conway Morris said.

As scientists discover new fossil specimens and re-examine fossils in museum collections, they may tweak the positions of ancient species on the tree of life. This new study suggests T. wellsi was a mollusk, but its taxonomic status is still up for debate. Mark Purnell, a professor of palaeobiology at the University of Leicester in England, told the Guardian that the presence of a radula does not definitively declare the species to be a mollusk, because animal lineages can evolve radula-like features independently from one another.

"It is still a very strange animal," Purnell told the Guardian. "[The researchers] have found some tantalising new information, but it is far from being a slam-dunk case in terms of definitely knowing what this weird thing is."

Conway Morris accepts that the radula could have evolved independently from mollusks and that future research may amend the new paper's findings, but he embraces that aspect of doing research.

"Welcome to science," Conway Morris said. "It's all work in progress."

The study was published online Sept. 21 in the journal Biology Letters.

Originally published on Live Science.

Patrick Pester is a freelance writer and previously a staff writer at Live Science. His background is in wildlife conservation and he has worked with endangered species around the world. Patrick holds a master's degree in international journalism from Cardiff University in the U.K.

Most Popular