Here on the little space rock we call Earth, humans often wonder whether or not we are alone in this universe. Though that question was not answered in 2020, many discoveries seemed to increase the prospect of extraterrestrial entities existing. Findings on the closest planet to us, in the outer solar system and the far beyond seemed to point to the possibility that other worlds could host organisms ranging from bacteria to technological beings. Perhaps, new results in the coming year will finally reveal who else might be out there.

Is E.T. phoning us from Proxima Centauri?

The answer to weird signals happening in the universe is never aliens, until maybe it is. Earlier this month, researchers announced that they had captured a very mysterious beam of energy in the radio part of the electromagnetic spectrum at 980 megahertz, coming from the closest star to our own. Proxima Centauri, which is just 4.2 light-years away, hosts one gas giant and one rocky world 17% larger than Earth that happens to be in its star's habitable zone, meaning liquid water could exist there. The unexplained signal reportedly shifted slightly while it was being observed, in a way that resembled the shift caused by the movement of a planet. Researchers are excited but cautious, explaining that they will need to figure out if more mundane sources, such as a comet, hydrogen cloud or even human technology, could be mimicking an alien signal, and that it will likely take time before they know one way or another if E.T. is phoning us.

Read more: Alien hunters detect mystery signal from the closest star system

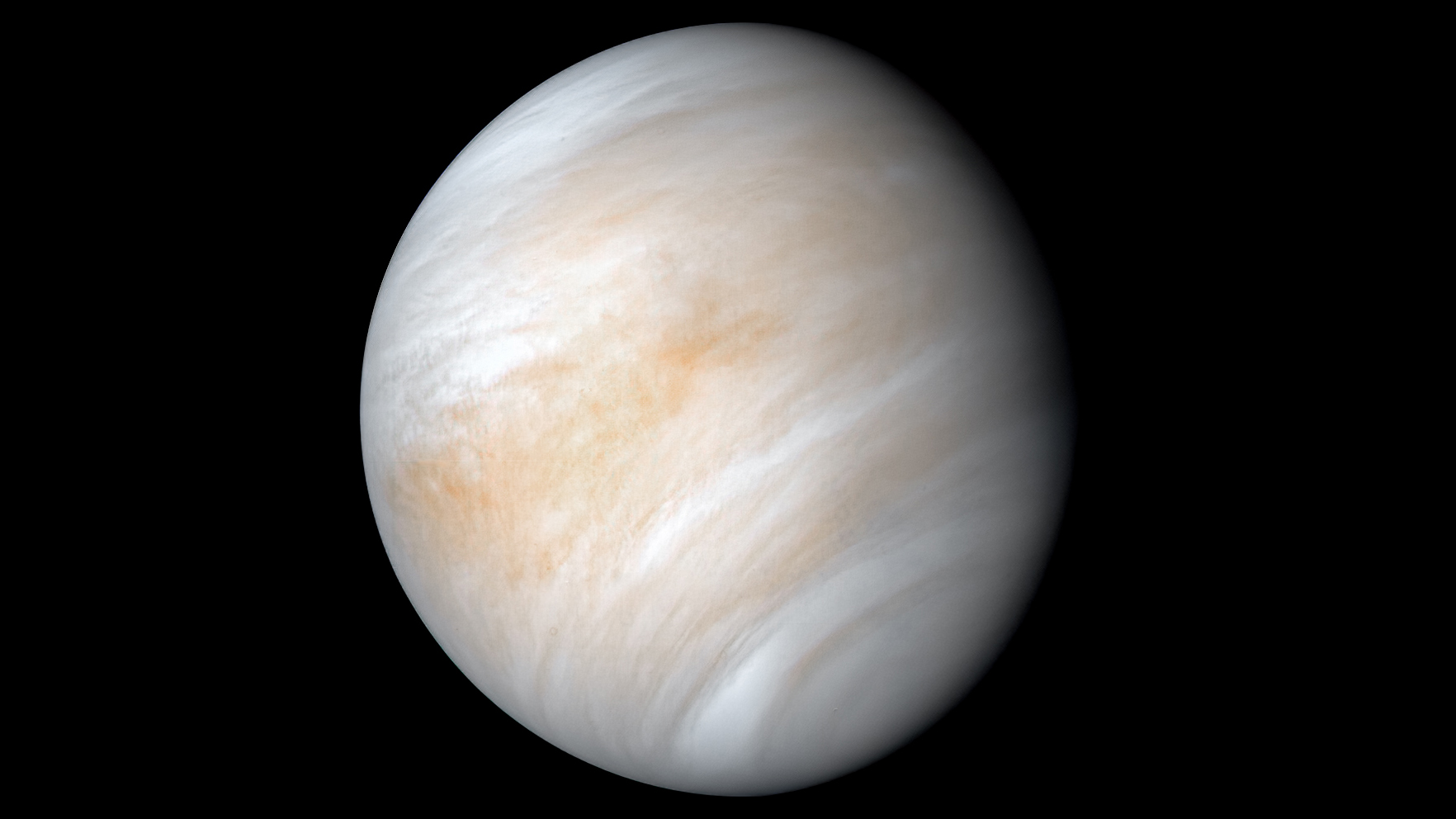

Alien bacteria might live in the clouds of Venus

Astrobiologists were a-twitter with anticipation and skepticism in September when news broke of potential evidence of life in the upper clouds of Venus. The announcement pointed to the presence of phosphine, a rare and often poisonous gas that, on Earth at least, is almost always associated with living organisms. With its hellish surface temperature, outlandish pressure and sulfuric-acid clouds, Venus has long played second fiddle to the seemingly more potentially habitable Mars. But a team aimed both the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii and the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array in Chile at Venus and picked up phosphine's signature in a Venusian cloud layer with downright Earth-like temperatures and pressures. Terrestrial bacteria are known to thrive in some pretty tough conditions, making the biological explanation a not unreasonable one. The research team doesn't claim that it is airtight evidence of space bugs, and many in the community aren't quite convinced, but if nothing else it will mean more funding in the hunt for life in unlikely places.

Read more: Possible hint of life found in the clouds of Venus

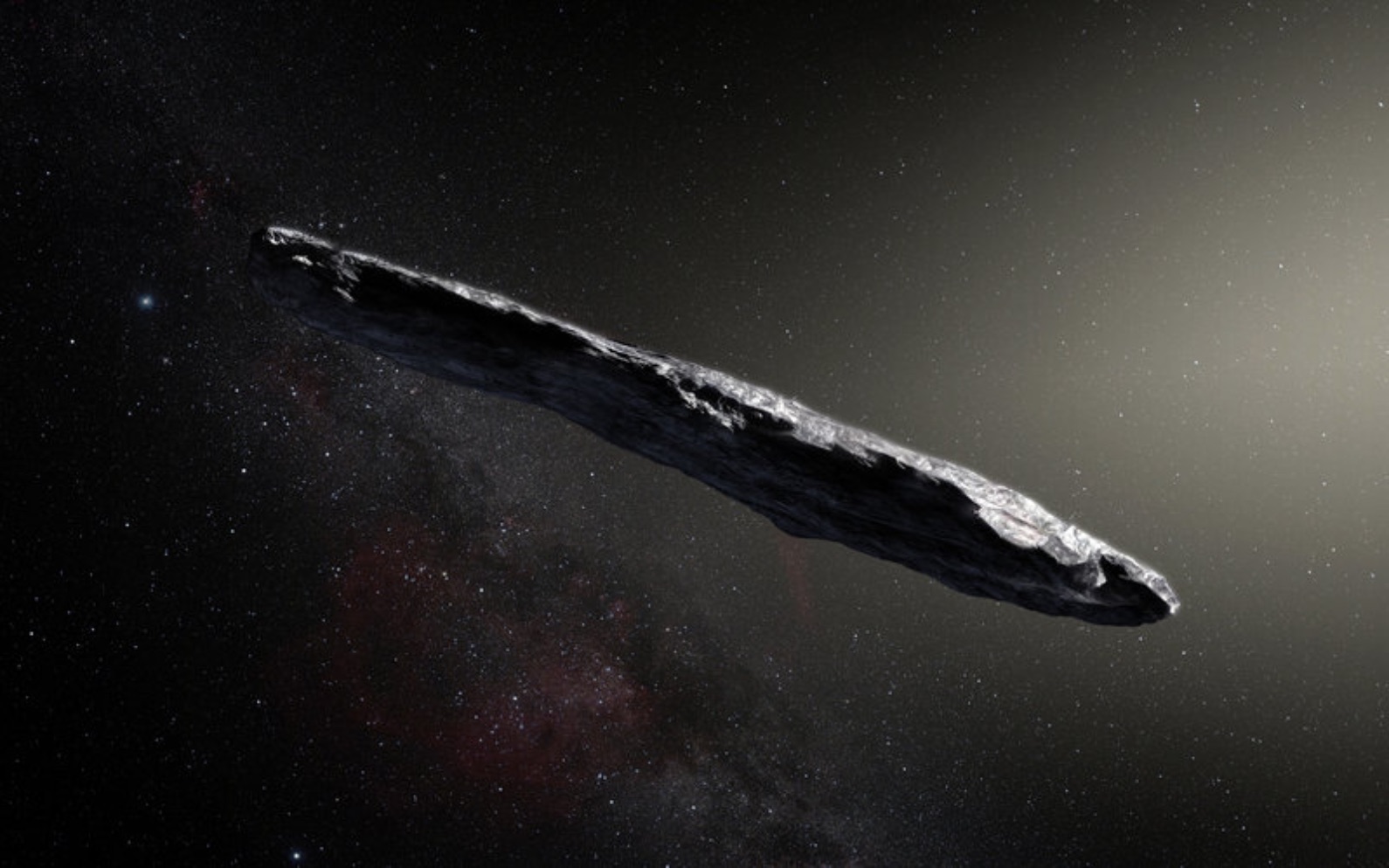

'Oumuamua could still be an alien artifact

Two years ago, scientists spotted a cigar-shaped object hurtling through the solar system. Dubbed 'Oumuamua, the entity is considered by most to be an interstellar comet flung out from around another star. But close observations showed that 'Oumuamua was accelerating, as if something were propelling it, and scientists still aren't sure why. Avi Loeb, a Harvard University astrophysicist has proposed that, instead of a comet, the interstellar visitor could have been an alien probe pushed by a lightsail — a wide, millimeter-thin piece of material that accelerates as it's pushed by solar radiation. Other scientists have thrown cold water on Loeb's idea, pointing out that hydrogen ice could have melted off the object in a way that was similar to a rocket engine or other propulsion method. But in August, Loeb fired back, writing in a study stating that hydrogen ice is very easily heated, even in the cold depths of interstellar space, and should have sublimated away before 'Oumuamua reached our system. It seems the debate might go on for a little longer at least.

Read more: Interstellar visitor 'Oumuamua could still be alien technology, new study hints

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Navy declassifies UFO videos but don't believe the hype

A fair number of Earthlings don't care what ambiguous evidence scientists come up with to show that aliens are out there. They are convinced that we've been visited by technological beings many times, pointing to stories about UFOs and alien encounters (pretty much all of which have been debunked). True believers received a boost in April when the U.S. Navy released footage captured by pilots that showed odd wingless aircraft traveling at hypersonic speed, looking for all intents and purposes like bizarre alien machinery. Despite the existence of such videos, people should still be wary, argued freelance journalist Sarah Scoles in her book "They Are Already Here: UFO Culture and Why We See Saucers" (Pegasus Books, 2020). After deciding to look into the Navy evidence, Scoles was unable to determine if it really showed alien aircrafts. But she found a much more human story by speaking to leaders in contemporary UFO culture and discussing our very basic need to believe in something beyond ourselves.

Read more: Navy declassifies UFO videos

Milky Way could be teeming with ocean worlds

Ocean worlds, which are classified as those having significant amounts of water on or just beneath their surfaces, are surprisingly common in the solar system. Earth is obviously one such place, but Jupiter's moon Europa is thought to host vast seas under its icy shell and Saturn's moon Enceladus is known to have watery geysers spewing from its exterior. Momentum is in fact building in the astronomy community to send a probe that could land on either satellite sometime in the 2030s and check if any living things might lurk under their shells. As for ocean worlds beyond our sun, in a study released in June, researchers looked at 53 exoplanets similar in size to Earth and analyzed variables including their size, density, orbit, surface temperature, mass and distance from their star. The scientists conclude that, of the 53, roughly a quarter might have the right conditions to be considered ocean worlds, suggesting that such places could be relatively common in the galaxy.

Read more: Ocean worlds could fill the Milky Way

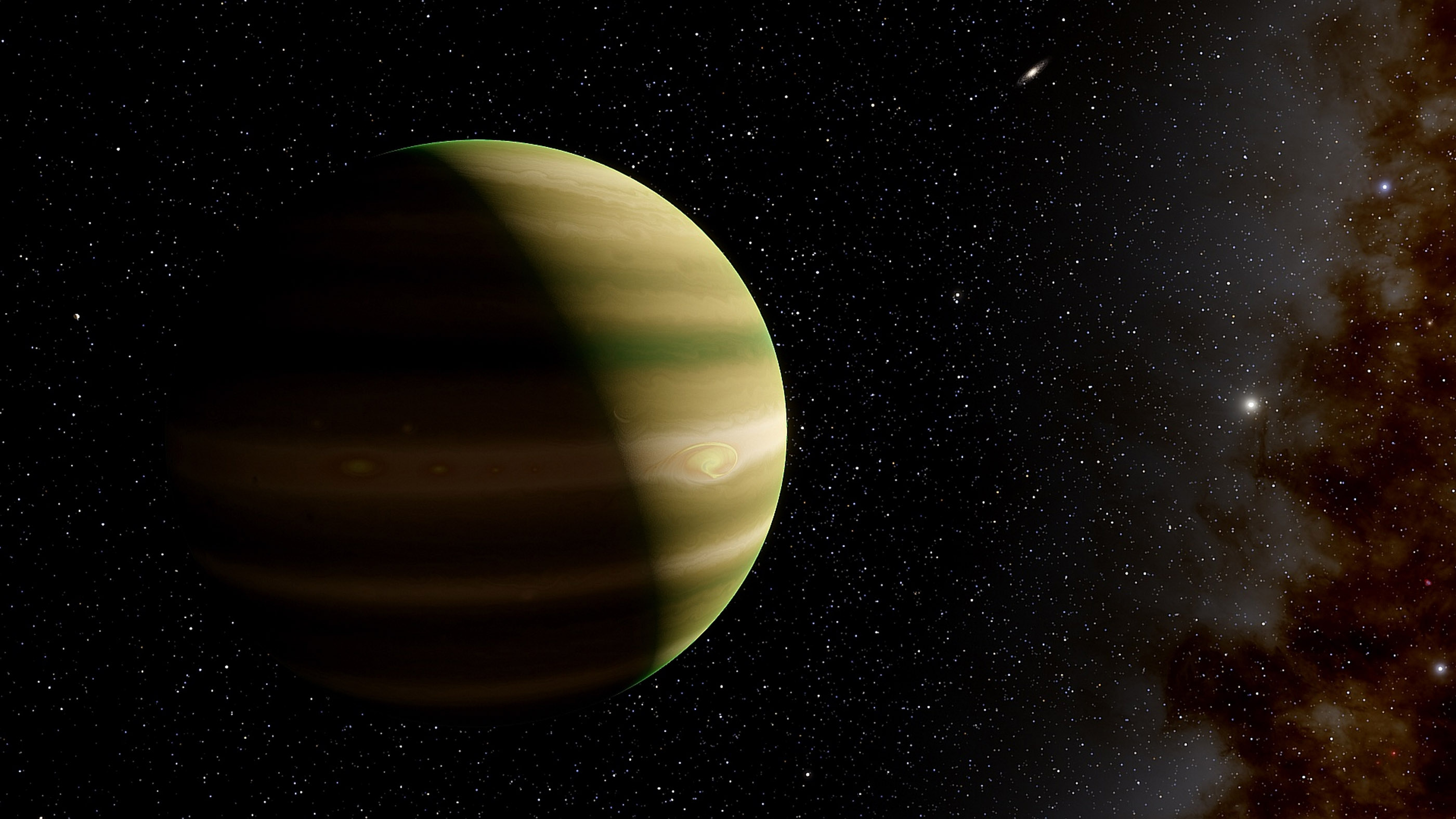

Earth bugs breathe hydrogen, maybe aliens do too

Most Earthlings require oxygen to survive. But oxygen isn't common in the cosmos, making up about 0.1% of the ordinary mass of the universe. There's far more hydrogen (92%) and helium (7%), and many planets, including gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn, are made mostly from these light elements. In May, scientists took E. coli (a bacteria found in the guts of many animals, including humans) and ordinary yeast (a fungus used to bake bread and make beer) and tried to see if they could live in different environments. Such microbes are already known to survive without oxygen and, when placed in a flask filled with either pure hydrogen or pure helium, they managed to grow, albeit at slower rates than usual. The findings suggest that when searching for organisms elsewhere in the universe, we might want to consider places that don't look exactly like Earth.

Read more: This bacteria can survive on pure hydrogen. Can alien life do the same?

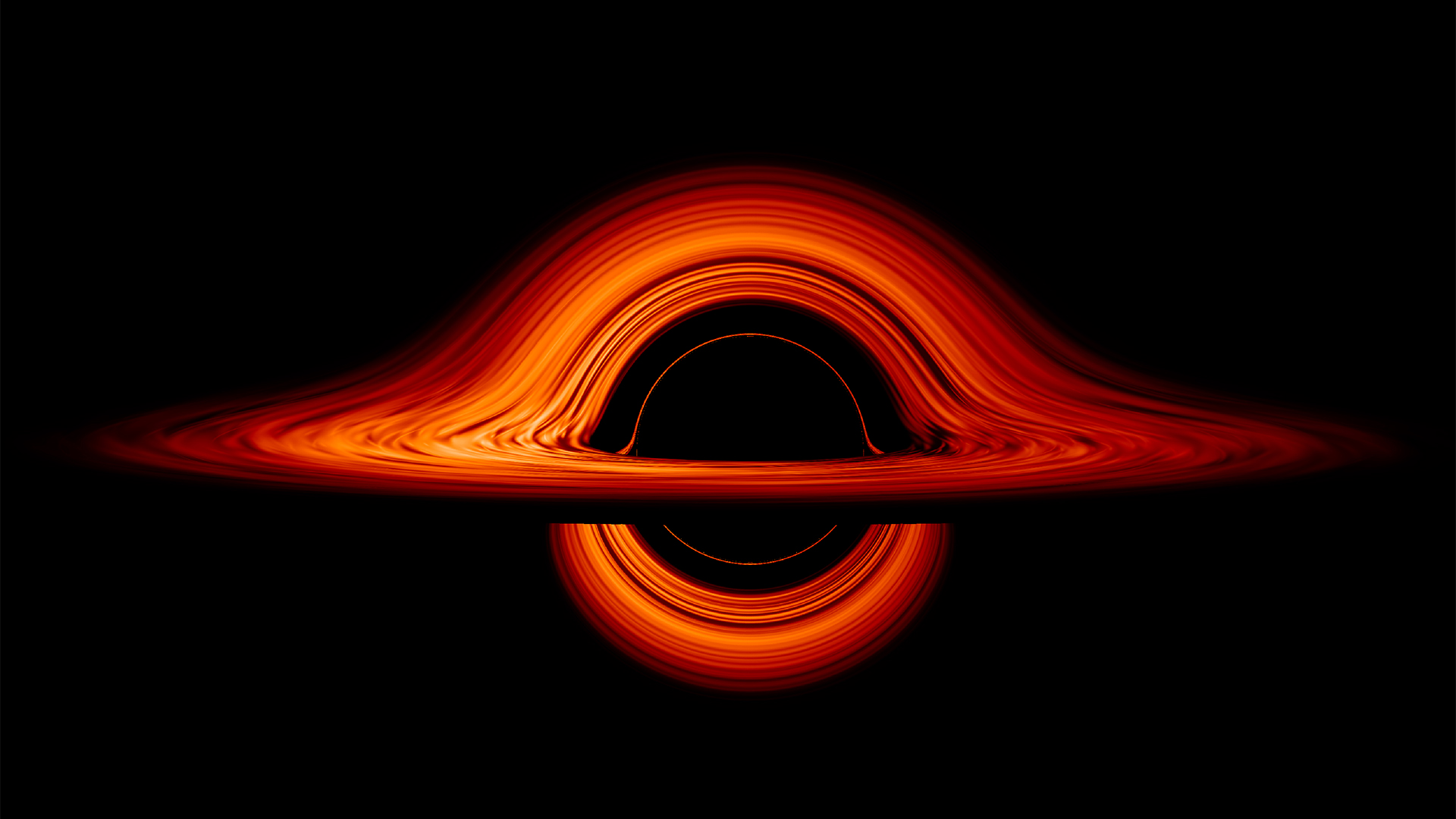

Life could live around a black hole

When hunting life on other worlds, most scientists stick to what they know — searching for Earth-size worlds orbiting sun-like stars. But far more exotic configurations could exist such as a planet circling around and heated by a black hole. At first glance, such a scenario seems absurd. But, contrary to popular depictions, black holes don't just suck in everything around them. Gravitationally stable orbits are possible and the light from the cosmic background radiation — a relic with temperatures at near absolute zero from the early universe that permeates all of space — would get heated as it fell into the black hole. As a paper released in March showed, this could provide warmth and energy to any organisms that happened to evolve in such a strange location.

Read more: Is life possible around a black hole?

1,000 places ET could be watching us from

As we hunt for beings beyond our planet, it's important to keep in mind that we might not be the only ones doing so. In October, researchers came up with a catalog of 1,004 nearby stars that would be in a good position to detect life on Earth. "If observers were out there searching [from planets orbiting these stars], they would be able to see signs of a biosphere in the atmosphere of our Pale Blue Dot," study lead author Lisa Kaltenegger, an associate professor of astronomy at Cornell and director of the university's Carl Sagan Institute, said in a statement. Using observational tools similar to the transit-timing methods that human astronomers use to study exoplanets, such alien onlookers could hunt for oxygen and water in our atmosphere and perhaps conclude that Earth is a good home for organisms.

Read more: Aliens on 1,000 nearby stars could see us, study suggests

Most aliens are probably dead

Where there's life, there's also death. While we like to imagine that our galaxy is teeming with technological beings capable of contacting us, the flip side is recognizing that all cultures rise and fall, meaning that plenty of cosmic societies likely bit the dust long ago. A model released in December put some numbers to these truths, taking into account such things as the prevalence of sun-like stars hosting Earth-like planets; the frequency of deadly, radiation-blasting supernovas; the time necessary for intelligent life to evolve if conditions are right; and the possible tendency of tool-bearing beings to destroy themselves. The analysis found that the highest probability of life emerging in the Milky Way likely happened around 5.5 billion years ago, before our planet even formed, suggesting that humanity is a relative latecomer to the galaxy and that plenty of our potential otherworldly partners are no longer around to talk to us.

Related: The Milky Way is probably full of dead civilizations

We should be open-minded as we search for life elsewhere

The human brain has plenty of constraints. We are misled by cognitive biases, optical illusions and inattentional blindness to things we don't expect to see. One question that has always dogged research into alien creatures is whether or not we could recognize life that is so different from what we encounter here on Earth. Scholars have long urged us to expect the unexpected, trying not to let theory too heavily influence what we count as significant. Life on other planets might not leave the same biological signatures as terrestrial organisms, making them difficult to spot from our vantage point. And, as Claire Webb, an anthropology and history of science student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told Live Science in January, we must train ourselves to "make the familiar strange," looking at ourselves through an alien lens in an effort to constantly reexamine our own assumptions. That way, we might be able to better understand ourselves through the eyes of another and perhaps meet creatures on other worlds on their own terms rather than ours.

Read more: To find alien life, humans need to start thinking like an extraterrestrial

Originally published on Live Science.

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.