Catastrophic Comet Chilled and Killed Ice Age Beasts

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

An extraterrestrial object with a three-mile girth might have exploded over southern Canada nearly 13,000 years ago, nearly wiping out an ancient Stone Age culture as well as megafauna like mastodons and mammoths.

The blast could be to blame for a major cold spell called the Younger Dryas that occurred at the end of the Pleistocene Epoch, a period of time spanning from about 1.8 million years ago to 11,500 years ago.

Research, presented today at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) in Acapulco, Mexico, could shed light on major questions about the megafauna extinction, the demise of the Clovis people, and an abrupt climate change.

“Based on the distribution of material, it looks like this impact probably occurred in southern Canada near the Great Lakes, over what at that time would have been a major glacier, the Laurentide ice sheet,” said one of the presenters, Richard Firestone of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Comet chemistry

They couldn’t find a distinct crater, suggesting the comet burst in the air rather than slamming into Earth. Even an airburst should leave its mark, so the scientists think the Laurentide Ice Sheet absorbed much of the impact.

A much smaller object burst in the air over Siberia in 1908, flattening 800 square miles of forest

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Firestone and his colleagues investigated buried carbon-rich layers dating back 12,900 years and blanketing more than 50 areas that span from California through Canada and into Belgium. They found a slew of extraterrestrial markers, including nanodiamonds, which are formed by energetic explosions in space, elevated amounts of the rare element iridium and tiny capsules of glass-like carbon.

“Glass-like carbon is essentially carbon that’s been melted at very high temperatures,” like those from a comet impact, Firestone explained. They also found elevated levels of the rare Earth element iridium that are too high to be from Earth.

Mega die-off

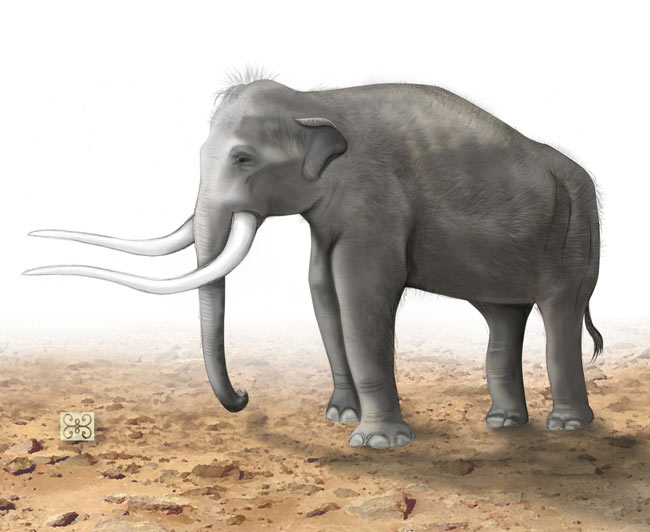

During the last catastrophic animal extinction, more than three-fourths of the large Ice Age animals, including woolly mammoths, mastodons, saber-toothed tigers and giant bears, died out. Scientists have debated for years over the cause of the extinction, with both of the major hypotheses—human overhunting and climate change—insufficient to account for the mega die-off.

An extraterrestrial explosion could have triggered a wave of massive wildfires that reduced to ashes the mastodons of the day, say the scientists. At one site called Murray Springs in Arizona, a well-known Clovis site, the scientists found megafauna covered by the comet debris.

“This black mat drapes over the bones of partially butchered mammoths as if somebody was in the process of working on these animals while they were actually killed,” Firestone told LiveScience in a telephone interview. “And between this black mat and the bones of this mammoth we find this ejecta layer. So it’s as if the [impact] event occurred right on top of these mammoth bones and then this black mat occurs on top of that.”

Once put out, the fires would have left a barren landscape devoid of food for any remaining animals.

“I would argue that most of the megafauna either died or starved after this thing,” Firestone said. “But certainly there must’ve been pockets of survival of large animals even mammoths that may have survived for thousands of years beyond that, ultimately to be hunted to death or whatever happened to them.”

Chill out

The comet theory could also explain the abrupt plunge in temperatures during the Younger Dryas period. Presenters at this AGU symposium argue that the comet impact or explosion would have heated up the area, causing the Laurentide Ice Sheet to melt and send massive amounts of water into the Atlantic Ocean. The input would affect ocean currents, which are responsible for keeping the atmosphere at livable temperatures.

Plus, the massive wildfires would have loaded the atmosphere with Sun-blocking dust, soot, water vapor and nitric oxides. The result would be the abrupt climate cooling.

The explosion would have been life-shattering for humans living in North America, particularly near the Great Lakes.

"It would have had major effects on humans," said one of the researchers, Douglas Kennett of the University of Oregon. "Immediate effects would have been in the North and East, producing shockwaves, heat, flooding, wildfires, and a reduction and fragmentation of the human population."

Any Clovis survivors would have been driven into isolated groups in search of food and warmth. Kennett said archaeological evidence at the Clovis sites is “suggestive of significant population reduction and fragmentation, but additional work is necessary to test the data further."

One thing is for sure, “It was a bad day in North America for those folks who were living there,” Kennett said in a telephone interview.

The evidence for a comet impact is substantial.

“I think the fact that there’s an impact is pretty definite. There are too many markers there for it all to be coincidence or happenstance explanations,” Firestone said, adding, “What will be debated is whether the extent of the impact was sufficient for instance to kill all of the megafauna or whether other factors were also equally important.”

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus