Found: Fossil Crocodile with a Mammal's Smile

Chew on this: A partial skull and jaw of a small crocodile relative that lived 100 million years ago has teeth that are more like a mammal's than a crocodilian's, according to a new study.

While crocodiles' toothy grins typically feature only cone-shaped teeth, this ancient crocodile relative from Morocco had more complex teeth, with specialized shapes that had pits surrounded by multiple pointed ends known as cusps.

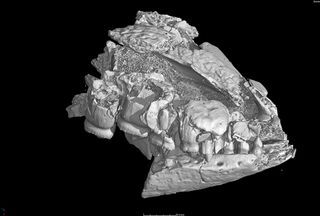

High-resolution X-ray computed tomography (CT) scans allowed the scientists to examine the fossil noninvasively and revealed layers of replacement teeth that would've emerged as old teeth were worn down. In addition, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) magnified details of wear patterns, which were likely created when the crocs cracked and pulverized the exoskeletons of insect meals. [Image Gallery: Ancient Beast Fossils Leap into 3D World]

The conical tooth shape in modern crocodiles is perfectly suited for the way the reptiles feed — tearing off large chunks of meat and swallowing them whole. Chewing, on the other hand, requires a different type of tooth structure that is commonly found in mammals, combining pointed and flat surfaces for crushing food before swallowing.

Fossil crocodilians with complex teeth, dating to the Cretaceous period (145.5 million to 65.5 million years ago), first emerged in the early 1990s, according to the study's lead author Jeremy Martin, a paleontologist at Laboratoire de Géologie de Lyon in France.

At that time, scientists identified them as mammal teeth, Martin told Live Science in an email. That all changed when those same types of complex teeth were found in jaws that clearly belonged to fossil crocodiles, "a group now known as the Notosuchia," Martin said.

The pint-size notosuchian revealed in this study was represented by an upper and lower jaw; the study authors said its snout would have been "short and triangular," and its body likely measured just shy of 2 feet (60 centimeters) in length.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But what it lacked in stature it makes up with an oversize name — Lavocatchampsa sigogneaurussellae. That mouthful of a moniker incorporates the names of three paleontologists: the late René Lavocat (1909–2007), who identified the first vertebrate fossils at this site, and Denise Sigogneau-Russell and Donald Russell, who discovered the small crocodilian in the Kem-Kem Beds of Morocco.

A wide variety of fossils have been recovered from this region, including dinosaurs, fish, snakes, pterosaurs and larger crocodilians, the scientists reported.

"The Kem-Kem Beds in Morocco have yielded a wealth of extinct creatures, mostly large animals," Martin said in a statement. "But with this discovery, we realize that part of the ecosystem remains untapped, especially when it comes to small-bodied terrestrial vertebrates."

A relatively small crocodile-like creature would have faced tough competition in this Cretaceous ecosystem, and would likely have benefitted from occupying a slightly different environmental niche than its larger crocodile cousins.

In fact, "the next step will be to understand their place in this peculiar ecosystem and understand how the ecosystem as a whole was functioning and evolving," added Martin, referring to the newfound croc.

The findings were published online Aug. 25 in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.

Most Popular