Paleo Construction Worker? Ancient Reptile Wore a 'Hard Hat'

Some 230 million years ago, an alligator-size reptile was crawling around what is now Texas with what looked like a hard hat on its head. That's according to a new analysis of the domed head of the ancient beast, a head that looks eerily like the skull of a pachycephalosaur dinosaur.

The ancient reptile, Triopticus primus, had this fashion sense a good 100 million years before pachycephalosaurs emerged on Earth.

It's anyone's guess why both T. primus and the pachycephalosaur developed thick, domed skulls, said lead study researcher Michelle Stocker, a vertebrate paleontologist at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, adding that this kind of phenomenon is called convergent evolution, in which two species come up with similar adaptations to live in a particular environment. [Dinosaur Detective: Find Out What You Really Know]

"It's difficult for us to say what this domed morphology would have been for or what would have 'encouraged' the evolution of this structure," Stocker told Live Science in an email. "None of the close relatives that we have for Triopticus in the Triassic have a similar structure to their heads."

One idea is that teenage pachycephalosaur dinosaurs had thick skulls so that they could butt heads, but it's unknown whether this newfound reptile did the same.

Workers with the Works Progress Administration, a government agency that employed people during the Great Depression, found the Triopticus fossil in 1940 near Big Spring, Texas. But it wasn't until recently that Stocker and her colleagues analyzed the fossil.

She and her colleagues named it Triopticus primus because a pit on the top of its head makes it look like it had a third eye, the researchers wrote in the study. In Latin, "tri" and "optic" translate to "three" and "vision," respectively, and "primus" means "first."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Since the workers found only the top of the skull, it was difficult to determine what the Triopticus looked like, but the reptile was likely no larger than an alligator, Stocker said.

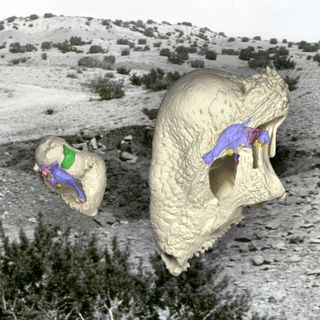

The researchers scanned the Triopticus' skull using computed tomography (CT) and found that some of the fossil's components looked similar to a pachycephalosaur's skull.

"The domed head of Triopticus is composed of thickened bone, with some internal 'zonation,'" Stocker said. "We can see partitions, or zones, in our CT scans of Triopticus that relate to different levels of vascularization and bone structure, similar to what is seen in pachycephalosaur dinosaurs."

Triopticus - partial skull & brain endocast by WitmerLab at Ohio University on Sketchfab

But there are also differences between Triopticus and pachycephalosaurs. For instance, Triopticus has a large pit in the top of its head that isn't seen in any dinosaur remains, and the structure of its braincase is different, too, she said.

Still, an analysis revealed that Triopticus is closely related to dinosaurs and crocodilians, and was part of a diverse reptilian fauna from the Triassic Period in Texas, Stocker said. If anything, the fossil revealed how much remains to be learned about dinosaurs and their relatives, she said.

The Triopticus specimen shows that "what we thought were unique features of dinosaurs were actually present much earlier," Stocker said.

The study was published online today (Sept. 22) in the journal Current Biology.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.